When I was eight I searched for something to read and found a white-jacketed book full of illustrations. It was about a bullied orphan who left boarding school to live in a haunted house and marry a black-haired man, and though now and then I had to ask my mother to decipher a word, I was enthralled. No one told me I was too young for Jane Eyre.

My parents are devoutly Christian, members of one of the few Strict Baptist chapels left in Essex. It's hard to explain how it was to be brought up in that chapel and that home: often I say, laughingly, "I grew up in 1895", because it seems the best way of evoking the Bible readings and Beethoven, the Victorian hymns and the print of Pilgrim's Progress, and the sunday school seaside outings when we all sang grace before our sausage and chips in three-part harmony.

Though we by no means resembled an Amish cult, there was an almost complete absence of contemporary culture in the house. God's people were to be "In the world, but not of the world", and the difference between those two little prepositions banished television and pop music, school discos and Smash Hits, cinema and nail polish, and so many other cultural signifiers I feel no nostalgia for the 80s and 90s: they had nothing to do with me.

Aside from the odd humiliation at school (asked which film star I fancied most, I remembered seeing Where Eagles Dare at an uncle's house and said, "Clint Eastwood") I don't remember feeling deprived. Because beside the Pre-Raphaelite prints that were my celebrity posters, and the Debussy that was my Oasis, there were books – such books, and in such quantities! Largely content to read what would please my parents, I turned my back on modernity and lost myself to Hardy and Dickens, Brontë and Austen, Shakespeare, Eliot and Bunyan.

I memorised Tennyson, and read Homer in prose and Dante in verse; I shed half my childhood tears at The Mill on the Floss. I slept with Sherlock Holmes beside my pillow, and lay behind the sofa reading Roget. It was as though publication a century before made a book suitable – never was I told I ought not to read this or that until I was older. To my teacher's horror my father gave me Tess of the D'Urbervilles when I was still at primary school, and I was simply left to wander from Thornfield to Agincourt to the tent of sulking Achilles, making my own way.

One beloved novel was Bulwer-Lytton's Last Days of Pompeii – I had no idea no one reads him now, or that he's accused of being the worst novelist to ever have disgraced the page. I simply was content to dwell in his Victorian ideal of a mythic past, safe at a double distance from the confusion of the world outside my door.

There were ancient books too, all gilded spines and Gothic script: a ghoulish child, I loved the woodcuts in Foxe's Book of Martyrs, and could tell you now precisely how Cranmer was tortured, and how his bones cracked in the flames.

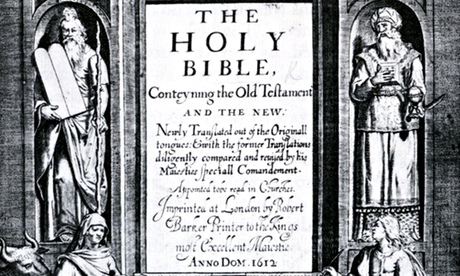

Above all – committed to memory, read aloud at mealtimes and prettily framed on the dining-room wall – was the King James Bible. It was as constant as the air, and felt just as necessary, and I think I know its cadences as well as my own voice.

The effect on my writing has been profound, and inescapable: I soaked it all up, and now I'm wringing it out. My obsession with rhythm and beauty comes, I'm sure, from memorising the King James Bible's peerless prose, and having grown up in the shade of sin and the light of redemption I suppose it's no surprise that my debut novel After Me Comes the Flood has been called uncanny, sinister, strange (though I never intended to write that way – it's just how my eyes were put in).

Sometimes I'm tempted to regret the youth that left me always a little at a loss, never quite belonging anywhere – but mostly I'm thankful it filled me with wonder at the strangeness of things, and gave me my voice.