In 1919, as Europe emerged from the carnage of the first world war, race riots broke out in Liverpool, which had justifiably called itself a "world city" during the Edwardian era; the city Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick, had described back in 1849 as "a port in which all climes and countries embrace". In his slipstream, visiting black Americans marvelled at the sight Melville had seen in Liverpool of a black ship's steward "arm in arm with a good-looking English woman", unthinkable in America.

Liverpool was host to Britain's first black community, but by 1919 some firms had discharged all their black employees, because whites refused to work with them. That year, gangs of up to 10,000 "John Bulls" and their supporters unleashed what the author of this book calls "a reign of terror… a white rampage" across areas of the city in which west African seamen had dropped anchor, followed by the Chinese. So ebbed and flowed the tides of race and race relations on the Mersey.

Local history at its best is both focused and universal: inimitably about a specific place in time, but with lessons for elsewhere and – if it is really good – beyond its time. Social historian John Belchem, Liverpool University's former pro vice chancellor, now emeritus professor of history, has made Merseyside his fiefdom of study over a number of books now, about the port city's "exceptionalism", about Irish migration and a vast history for Liverpool's 800th birthday in 2007. With this – his best – book, Professor Belchem tells a story from the Mersey that not only speaks to the British present, it roars.

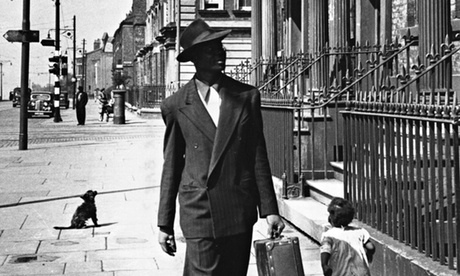

There have been some excellent – albeit too few – books about black Britain and migration to Britain and most of them begin with the arrival of the Empire Windrush from Jamaica in 1948. Liverpool, however, was by then well acquainted with the themes of "cheap labour" from the empire and racism in the mother country, embrace and rejection, hence Belchem's rightful claim for his study as "a prehistory as it were, of the deleterious race relations which accompanied (and besmirched) the otherwise vaunted transition from authoritarian empire to libertarian commonwealth".

What the rest of Britain and the new arrivals found out about themselves and each other from the late 40s onwards, Liverpool had rehearsed and demonstrated over decades. "Their legal status as British subjects notwithstanding," writes Belchem, "'coloured colonials' in Liverpool were the first to discover that 'There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack'".

We begin in 1907, when "polyglot Liverpool" sought to distance itself from the slave trade and its legacy, and from the provincialism of the industrial hinterland. But the riptide of reality cut beneath this "Edwardian cosmopolitanism": Chinese sailors were like "an international octopus", said dockers' leader James Sexton. The city fathers' promotion of cosmopolitanism was accompanied by demands for restrictive legislation.

The riots of 1919 were levelled against immigrants seen as stealing work and women from the returning white troops – one way to regard the relatively speedy settlement of many west Africans who were marrying girls often from Irish families; the origins of that singular, maritime ethnic identity, the "Liverpool-born black". (One American anthropological history even calls them LBBs, as though a species of their own.)

But the tale Belchem then vividly relates is as generic as it is singular: one that repeats over and over – in prophetic microcosm for all to heed, but in the event ignore – the dichotomies and contradictions that ride on every breath behind today's toxic discourse blaming immigrants for unemployment among whites while the calculations of capitalism require labour as exploitably cheap as it will come.

At first, there was a lure of the "exotic". JB Priestley wrote of the Irish north end of the city: "I suppose there was a time when the city encouraged them to settle in, probably to supply cheap labour. I imagine Liverpool would be glad to be rid of them now", while the cosmopolitan south side delighted him, in his way: "Imagine an infant class of half-castes, quadroons, octoroons, with all the latitudes and longtitudes mixed in them."

Elsewhere, consternation over what were repellently called "half-caste" children reached obsessive levels, even to the point of eugenic fascination. There is also the intriguing theme of how harmonious race relations were pursued by the Colonial Office not so much out of humanity as fear of the radicalising impact discrimination would have in the colonies themselves, as they moved towards liberation from empire.

For multifarious reasons that befit a port city – despite further riots after second world war, and widespread discrimination in employment and accommodation – Liverpool "emerged as a model for race relations in the 1950s", avoiding the tribulations of Notting Hill and Nottingham during summer 1958.

But while Beatlemania and Merseybeat conquered the world, not all was quite so "cool" back home. There were race riots in 1972, of which Belchem writes: "While local authorities and politicians continued to vaunt the city's harmonious reputation … the riots… [were] a siren call, warning of trouble ahead elsewhere as British-born black children of the Empire Windrush generation approached adolescence, alienation and racial polarisation."

I lived in Liverpool 8 during the late 1970s and early 80s, and spent many nights in the cellars of the Casablanca, Silver Sands and Somali clubs, which I am delighted to find acknowledged in Belchem's account of the bohemian, shebeen scene. I also watched, as Belchem describes, "urban planning" in Liverpool become synonymous with urban blight and remember the tension that ratcheted up between black youth and a predatory, racist police force – and erupted in the so-called "Toxteth riots" of 1981.

Much has been written about the riots, and there is plenty here, Belchem's point being that in their wake, once proudly "cosmopolitan" Liverpool stood condemned for racism that was "uniquely horrible" even in Britain. But Belchem's book narrates both the ugly and the good. At one point during the second world war, the Elder Dempster shipping company sought simply to deregister its west African crews and re-register them back home, with a view to paying African wages to British citizens. The retort is also part of Belchem's story: "We have been told," thundered the indefatigable Pastor Ekarte of the African Seamen's Mission, "that this country is fighting on behalf of defenceless people. If so, we defenceless seamen appeal to you to defend us."

Belchem's predominant story of black Liverpool weaves inevitably into that of white migrants to the city, mainly Polish as well as Irish. During tensions between indigenous and "alien" workers from eastern Europe after the second world war, a delegate addressed the Trades Union Congress: "How do the people of Liverpool feel when they see these Poles… strutting about our streets, when our boys from Burma, heroes from Arnhem, pilots from the Battle of Britain, have to take their wives and families and go squatting?"

The fact that the Polish pilots had flown gallantly in the Battle of Britain was apparently irrelevant. White riots ensued against Jews (two years after the British liberation of Belsen); followed by a pogrom of deportations of Chinese and west African seamen, with "colonial clubs" attacked during serious fighting between white and blacks across Liverpool 8, in response to which the police removed "the problem" – the blacks.

So roll over, Nigel Farage: longer than anywhere else in Britain, Liverpool has heard it all before and knows where it leads.