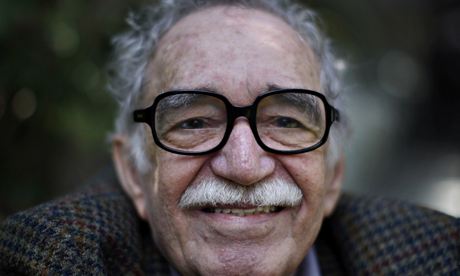

Not many pillars of literature who held the century past upon their shoulders lived this far into the 21st. Seamus Heaney, Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel García Márquez were among the very few in their league to remain among us until recently, and now the last of that triad has departed — arguably the last epic novelist of his generation; the inspiration for the Latin American renaissance of the 1960s and "the greatest Colombian who ever lived", according to the tribute from that country's president, Juan Manuel Santos.

The critics and obituary writers will reach for the right genre to apply, probably converging on "magical realism" – that way in which the everyday, the vernacular, relates and expands through some drawn-back veil of consciousness to the extraordinary and the questions that propel, or sanction, human existence.

But among the many things that made "Gabo" great was that he defied genre. While One Hundred Years of Solitude, written during the mid-1960s, had an almost Zola-esque span and genealogical ambition to it, propelling history forward on an epic scale, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, the story of a murder committed 30 years before its publication in 1981, narrows its focus into a forensic inquiry backwards in time to the point of claustrophobic intensity.

The whimsical Memories of My Melancholy Whores was a sufficiently strange account of a very old man's romantic fixation with an adolescent girl to secure García Márquez condemnation from religious circles worldwide, while News of a Kidnapping remains the single most outstanding work of documentary Latin American non-fiction, charting a spate of connected kidnappings by the Medellín cartel of Pablo Escobar (the second most famous Colombian of all time), with attention to physical and psychological detail that plunges the narrative into the nightmare that it was.

Colombia's violencia of the 1950s and 60s– and subsequent narco, paramilitary and guerilla wars – infused almost all he wrote. After all, Márquez's fame enabled him to act as a mediator between successive governments and its enemies. His productive decades spanned those in a country – a continent, indeed – of extreme political tumult.

Fidel Castro and Márquez became friends – some say he was the Cuban leader's closest confidant at times – a bond which cost the Nobel laureate a fist in the face from the political nemesis who lived and worked forever in his shadow, Mario Vargas Llosa.

But in this maelstrom of a lifetime, and its reported twilight suffering dementia, it is words across pages that speak louder than, and endure beyond, the extraordinary deportment of the man. As he wrote: "What matters in life is not what happens to you, but what you remember, and how you remember it."