If you are following the career of Sarah Moss, this is an exciting moment. Her third novel confirms the richness of her concerns (remoteness, maternity, how we make life hard for each other) and it sharpens our sense of her steely, no-nonsense voice. It suggests that, though her books are closely linked, she has much more to write and will never produce the same thing twice.

First there was Cold Earth, set in Greenland and narrated by a group of archaeologists exhuming the Viking past and facing their own ends. Then there was Night Waking, set in the Outer Hebrides, where a sleep-deprived mother of two small boys tries to write her book in 15-minute snatches. In between, she recites The Gruffalo, wonders if she might kill someone and is interviewed on suspicion of having actually killed someone, while her vilely nonchalant husband carries on counting puffins. That was written while Moss herself was living in Iceland for a year with her young family, dealing with all the comically fascinating problems she recounts in her memoir, Names for the Sea, such as how to buy a cheap fridge in a country horrified by anything second-hand.

The historical strand of Night Waking, dug up along with a bundle of infant bones in the orchard, involved a young Victorian nurse called May Moberley; Bodies of Light tells the story of the Moberley family, particularly May's sister Ally, in central Manchester in the 1860s and 70s. These paths between novels – the publishers promise a further book in the same loose sequence – suggest a taste for Norse and Lawrentian saga. Ally's coming-of-age story would have been enough of a plot, but Bodies of Light encompasses two generations, looking back to the youth of Ally's mother, Elizabeth, who will inflict on her daughters the same constant stream of spirit-quashing punishments she herself experienced as a child. By the close, Ally seems to have escaped her mother's stern grip, but one suspects that Moss's interest in inheritance will reassert itself in whatever is to come.

One of the central subjects here is the domestic cruelty of a zealous social campaigner. In her ruthless march of virtue, Elizabeth Moberley stamps out her family's small attempts at warmth and joy. Hers is a variant of the "telescopic philanthropy" skewered by Dickens in his portrait of Mrs Jellaby, though Elizabeth certainly gets her hands dirty for the women's causes she promotes, and she obsessively controls her family rather than ignoring it.

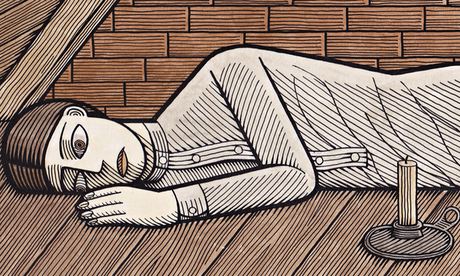

Control is her religion. Under her roof no feeling is allowed free rein; excitement, hunger and fear must all be governed. When Ally has nightmares as a teenager, as well she might, she is ordered to control her dreams; sent to sleep on the attic floor, she lies in exposed loneliness, "vulnerable as a wounded animal". As a training in the silent bearing of pain, Elizabeth burns her daughter with a candle. This is mortification of the flesh as extreme as monastic hair shirts and flagellation. It masquerades as moral education, but it is savage familial violence, injurious to body and mind alike.

Moss is too challenging a novelist to allow us simply to despise Elizabeth. We must respect her tough commitment to her work as she pushes into the brothels and asylums of mid-Victorian Manchester's dismal underworld. We know that, as a child, Elizabeth was made to walk with stones in her boots to remind her, at every step, of her sins. If her own reforming drive came of such an upbringing, she has reason to teach her daughter the same perverse discipline.

Moss has written before about difficult motherhood. She was brave enough in Night Waking to describe maternal boredom, exhaustion and self-loss in ways that probably attracted hate mail but also made her novel book of the month on Mumsnet. In Night Waking, she narrates Elizabeth's dread of sharp baby gums attacking her breasts and the need to hide the means of suicide from a mother's desperate hands. When Elizabeth later punishes her daughter for nervous weakness, she is expressing – through repression – her fear of mental instabilities she recognises well.

Moberley life is grim, and the novel persists grimly. Frankly it persists too long, though it is sustained by its tonal mix of acerbity and tenderness, and by a vein of black comedy. "Did you hear of the girl who, on her wedding night, left her husband in the drawing room while she went upstairs and chloroformed herself?" Such is the tenor of Elizabeth's comments to her husband at the start of their honeymoon. "That does not sound encouraging," replies Albert, aware that his wife is riding backwards in the train because she would rather not look ahead.

The novel is sustained, too, by historical detail that is vividly and feelingly done. Disparate Victorian milieus are made to collide. There is Elizabeth's world of activists, working relentlessly, running homes for the destitute, exposing sexual double standards. And there is the pre‑Raphaelite circle of Alfred, an artist who muffles himself among deep-dyed fabrics and gazes on the bodies of his sitters as he turns them into nymphs. He paints Elizabeth as the Virgin in an Annunciation, but she does not want to sit in sacred stillness. He paints the adolescent Ally as Proserpina going into hell, making a picturesque myth out of the truly hellish breakdown his daughter is undergoing and which, though she stands naked before him, he refuses to understand.

Ally breaks free from both parents to study in London as a medical student, becoming, in 1880, one of the first women physicians in Britain. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had been practising privately since 1865 but had not been licensed to work in a hospital. The fictional Ally and her small band of peers, loosely based on the Edinburgh Seven, are the first British women to bear the name of "doctor". Moss imagines their daily struggles for the right to undertake surgical stitching rather than embroidery; when at last Ally wields her scalpel it is with triumph rather than nausea. Unaccustomed to happiness, Ally has no idea how to celebrate her achievement. One might detect this predicament in the writing of Sarah Moss, who produces well-crafted, deeply researched, hard-working novels about hard-working women. Might her taut, dry humour be allowed, in future, freer expression? Might this tremendously talented writer find some cause for celebration?