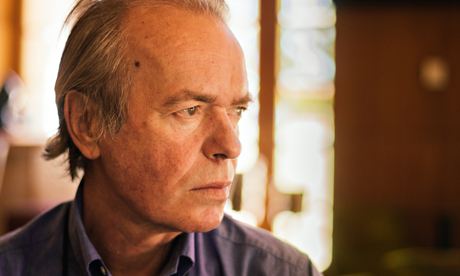

Like a schoolboy lobbing stinkbombs through an open window, Martin Amis has been holding forth on cohesion as we experience it, and getting quite a lot of stick for it. America is an immigrant nation, he says. The Pakistani in Boston, says Amis, could call himself American, while the Pakistani in Preston couldn't call himself English (without raising an eyebrow): "There's meant to be another layer of being English. There are qualifications other than citizenship and it's to do with white skin."

This might tell us more about the company Amis keeps than the views of the general population; especially if you tire of these showy contributions from someone who spends most of his time somewhere else. But there are indeed those who insist that while minorities can be British – at a push – they cannot really be English. It's the sort of line you might encounter at dinner parties thrown by old-style rightwing Tories and was once an approach much favoured by the nastier columnists in the Spectator. The less discerning football hooligans held fast to the idea too. Old timers will recall how they would refuse to acknowledge any goals scored by black England players, such as John Barnes and Laurie Cunningham. Seems almost comical now.

Yet, Amis may have a point. If the stats are to be believed, many people continue to associate Englishness with whiteness. According to census analysis by the ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity at Manchester University, 72% of white Britons and 47% of those of mixed heritage described themselves as English rather than British. In terms of religion, Christians and Jews were more likely to claim an English-only national identity. Then there were interesting stances taken by those who described themselves as mixed.

"Three fifths of the mixed white-Caribbean and two fifths of the mixed white-Asian groups describe themselves as English only," report the analysts. "This suggests English is predominantly a white identity which some people feel they have access to. More than a quarter of the Caribbean and black-other ethnic groups also report only an English national identity, suggesting that some people in the ethnic minority groups that are most likely to have mixed offspring are able to feel an English identity too." What does that tell us? Old habits die hard. Change takes time.