At the end of October 1943, Joseph Goebbels visited Hitler at his military headquarters in East Prussia – the Wolf’s Lair. The war had turned against Germany and they discussed the options for making a separate peace, Hitler leaning towards a renewed pact with Stalin, Goebbels favouring an agreement with Britain, even though neither was a realistic possibility. “I have no idea what the Führer’s going to do in the end,” wrote Goebbels. What Hitler did was retreat increasingly into a fantasy world in which a new German counter-offensive, the deployment of “wonder weapons” such as the V1 and V2 rockets, or a falling out among the Allies would rescue the Third Reich from inevitable defeat. And when it became obvious even to Hitler that this would not happen, he killed himself, on 30 April 1945. Goebbels followed suit the next day. He and his wife first killed their six children before taking their own lives.

Peter Longerich, the author of previous works on the Holocaust, as well as a biography of Heinrich Himmler, has now written the most comprehensive account we have of Goebbels’s life. Based heavily on the detailed diaries that Goebbels began to keep in the autumn of 1923 – 32 volumes in all – the biography presents the Nazi propaganda chief as a narcissistic personality constantly seeking recognition. Born in 1897 into a lower-middle-class family in the Catholic Rhineland, he was a talented but wayward student who completed a doctorate at Heidelberg on a minor figure from the German Romantic movement. He saw himself as a major writer, produced a string of unpublished works, and at the time he began his diary was an isolated, resentful figure under the sway of a fashionable cultural pessimism.

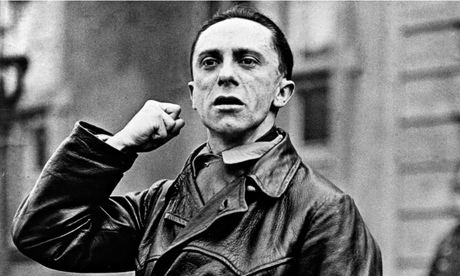

After drifting into the rightwing völkisch movement, he discovered Hitler and became a true believer in this “political genius” who was “half-plebeian, half-god”. Goebbels quickly became a local leader of the National Socialist party in western Germany; his gift for incendiary political articles and speeches then brought him to national prominence. He became Gauleiter of Berlin in 1926, was elected to the Reichstag two years later and appointed director of propaganda for the whole of Germany in April 1930. That gave him an important role in 1932, the year of four major election campaigns, although Longerich plays down his success as a propagandist. Goebbels remained a relatively isolated figure within the Nazi party as it became a mass movement, lacking a network of allies and wholly dependent on Hitler’s support. He resented the coterie of figures who surrounded the Führer at party headquarters in Munich and clashed with other leading figures, such as Gregor Strasser and Hermann Göring (“a lump of frozen shit”). Goebbels reacted largely as an onlooker to the series of tactical twists and turns in party policy that preceded Hitler’s appointment as Reich chancellor in January 1933.

Hitler was aware of Goebbels’s devotion and sometimes exploited it to keep his acolyte twisting in the wind. This happened after the Nazis came to power, when the major ministry that had been promised failed to materialise at first and Goebbels fumed (“I’m being pushed out of the way. Hitler doesn’t help much.”). He got his wish in the end, however: a Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda that ranged over the press, theatre, cinema and broadcasting. Horribly familiar episodes in the Nazis’ brutalisation of German culture, from the book burning of 1933 to the “degenerate art” exhibition of 1938, bore Goebbels’s signature. His ministry was also responsible for public displays, rituals and mass rallies: the staging of politics that was such a feature of the Third Reich. Goebbels had a large part in constructing the image of a unified Volksgemeinschaft (“people’s community”), although Longerich is rightly sceptical of the view that all Germans “lived in a kind of totalitarian uniformity” during this era.

Longerich is at his best describing day-to-day politics, but he also writes about Goebbels the private person. In the first part of the book we read of many women with whom he had affairs – Anke and Else, Elisabeth and Alma, Dora and Tamara, Hannah and Johanna, Xenia and Erika – but most remain little more than names. Then, in November 1930, he met the attractive divorcee Magda Quandt. They were married a year later with Hitler as a witness. He then became, in effect, the third member of a strange triangular relationship that installed Magda at the Führer’s side as a sort of first lady of National Socialism. Hitler became practically a family member, a frequent visitor who was very close to the Goebbels children, all of whom had names beginning with H. When the marriage nearly ended in 1938 because of Goebbels’s affair with Lida Baarová, Hitler insisted that they stay together. The family lived in great material comfort. Before the Nazis came to power the “radical” Goebbels spouted anti-bourgeois rhetoric and usually wore a leather jacket or an old trench coat. After 1933, he dressed in tailored suits. His residence in Berlin, greatly expanded in 1939, had a staff of 18. There were additional homes on the Bogensee and on the fashionable Wannsee island of Schwanenwerder. He liked fancy cars, and soon after he and Magda moved into the Schwanenwerder summer residence in 1936 he bought his third new boat since taking office. The war changed none of this, at least initially. Goebbels proudly acquired a new Mercedes in 1940 (“a magnificent car”), while the occupation of France provided the opportunity to acquire valuable rugs, furniture and artworks at the expense of the propaganda ministry.

Goebbels remained outside the inner circle of decision-makers as war approached. He knew nothing in advance about the Nazi-Soviet pact, for example; his role was to prepare the German people psychologically for war. After hostilities began he remained the great choreographer of enthusiasm and resolve. The wartime years were accompanied by another change of costume. Elegant suits now gave way to party uniform, in which Goebbels delivered what Longerich calls his “most important but at the same time his most repulsive rhetorical performance”, the speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 18 February 1943, in which he spoke of the need for “total war” and excoriated the Jews who guided Germany’s enemies.

Here the propagandist spoke with inner conviction. Goebbels was a virulent antisemite from his earliest days in the Nazi party and played a leading part in “Jewish policy” after the seizure of power, from the boycott of Jewish stores in 1933 to the November pogrom of 1938. During the war, he pressed hard for Berlin to be made “free of Jews”. “It seems grotesque that there are still 75,000 Jews in Berlin,” he wrote in August 1941. Antisemitism was as central to the wartime propaganda his department produced as it had been to earlier campaigns aimed at removing “alien” influences from German culture. After the genocidal policy began he wrote in his diary of deportations and liquidation. A long entry in March 1942 included the following: “A judgment is being carried out on the Jews that is barbaric but thoroughly deserved. The prophecy that the Führer gave them along the way for bringing about a new world war is beginning to come true in the most terrible fashion. There must be no sentimentality about these matters.” The Führer, he added, was the “unswerving champion and advocate of a radical solution”.

Goebbels’s faith in Hitler remained largely undimmed as the war closed in on Germany, and he was rewarded for his loyalty. After the July plot of 1944, he was named Reich plenipotentiary for total war and could now get his own men in the ministries of party rivals such as Alfred Rosenberg. As other leading Nazis such as Göring, Albert Speer and Himmler lost Hitler’s confidence, so Goebbels’s star rose. But the position he had always craved came only when it was evident to everyone but Hitler that the war was lost. The last surviving entry in his diary came on 10 April 1945. Eleven days after that, he, Magda and the children moved into the Führerbunker to await the end.

• To order Goebbels go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.