I am lately returned from a pilgrimage, bearing bloodied knees and a holy relic; my destination was a place of love and sacrifice that’s lived long in my heart. No Lourdes for me, though: I went to the Reichenbach Falls.

Lifelong Holmes devotees view the current Sherlockian fad with exasperated pride. On the one hand, any Holmes is better than none. On the other, the BBC’s Sherlock left me speechless with indignation: that Conan Doyle’s (almost) unfailingly courteous, just and asexual Holmes was reduced to a drunken, rude, sentimental sociopath had me calling for the reinstatement of the blasphemy laws.

My own affair with Holmes – which involves no girlish swooning – began early. I read my father’s old Penguin Complete Holmes incessantly. I dreamed about the speckled band; I wrote my name in dancing men. I wept when the injured Watson saw, “for the one and only time”, that glimpse “of a great heart, as well as of a great brain”. As a teenager, I’d listen to Radio 4’s adaptations, pretending that I too saw the pea-souper press against the window. Gravely ill in Manila, I leafed through that old Penguin volume for the consolation of home.

Last month, the composer Stephen Crowe and I boarded the first of four trains to the Swiss town of Meiringen. We took with us that day The Final Problem, in which Conan Doyle, sick of his creation, chucks him off a rocky ledge. Watson recounts: “We made our way … by way of Interlaken, to Meiringen.” Changing trains at Interlaken, I grinned like a child.

We consulted the story: what did they eat at the Englischer Hof? Could we eat it, too? Though I’d predicted a parade of devotees dressed as Mrs Hudson, when we arrived at Meiringen there was not a Holmesian in sight. But the square is named for Conan Doyle, and a chalet resembling a cuckoo clock bears a London street sign reading 221b Baker Street. Up to his ankles in snow, a bronze of Holmes sits eternally contemplating clues. Stephen sat briefly on his knee.

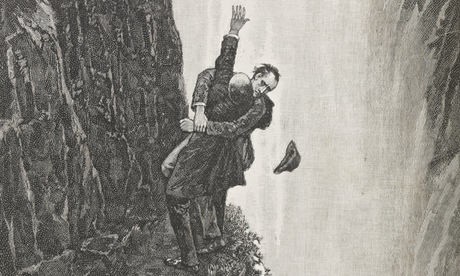

There was no Englischer Hof, but a cafe serving beef soup. “Which way to the Reichenbach Falls?” we asked, but a slight mispronunciation caused confusion. We sought directions from a woman on a bridge. “Holmes?” she said: “They’ve turned the water off. The waterfall is dry!” Stephen plucked off his hat and threw it down in Victorian disgust; but no sense giving up, we said, and set out. The funicular was closed for the season: we’d have to make it up alone. No need for a map – Watson’s account would suffice.

As we climbed into winter I wondered whether my ability to walk miles on Norfolk flatlands might not cut it. Stephen left barely a footprint; lagging behind, I’d skim a step or two then sink to my knees. “I can’t die yet: I have editing to do”, I thought, keeling over. “Nice I get to be Holmes for once”, said my friend, watching my slow progress. He broke a branch from a nearby tree. “An alpine-stock!” he said (a reference to the walking-stick Holmes left behind as he went to his apparent death), and threw it kindly down.

Watson describes “a fearful place. The torrent, swollen by melting snow, plunges into a fearful abyss”. But how would we find the Falls, if they’d turned the torrent off like a kitchen tap! We came to a stone bridge under which a stream fell perhaps six feet. Was this it? Certainly you’d do no end of damage if Moriarty were to shove you in. But no: there was no “creaming, boiling pit of incalculable depth”.

A little further on, contemplating another disappointing candidate, Stephen paused, and gestured upward. And there it was: a sheer black rock face, split in the centre, against which the remains of the Falls formed a gleaming drapery of frozen spray. Below it the Reichenbach river bore blue blocks of ice sheared off from further upstream; above it, on the mountain rim, a few pines were black against the sky. We were entirely alone.

“That’s it!” we said, reassuring and doubtful by turns. “Isn’t it? Yes! It must be!” I could go no further, but my friend darted on, crossing the stream, standing as if conjured up by Caspar David Friedrich. Meanwhile, my 11-year-old self, never far away, laughed in delight.

“A few words may suffice to tell the little that remains”, as Watson put it. I made my way down in terror; we bought thick socks for our frozen feet; we missed two trains in order to visit the Holmes Museum, inexplicably opening at 4.30pm, but no one ever came. In the station cafe we consulted a postcard for clues. Had that really been it? Look, there, at the particular cleft in the rock; at that line of trees! It was. It must have been.

On my desk as I write, I have all that remains of my alpine-stock, together with my beloved Penguin Holmes. I still don’t know whether we took a wrong turning; whether yards away, concealed by a rift in the rock, tourists took their photos beside a plaque recording the sad events of 1893. But it doesn’t matter: to be a reader is to believe, and I believe that we were there.

• Sarah Perry’s After Me Comes the Flood is published by Serpent’s Tail.