The Riders is probably the only opera to feature an American Express office. But then Tim Winton’s novel, on which it is based, is a nightmarish travelogue as much as a story of unexplained loss. So the credit facilities and travel hubs (Shannon airport, Paris’s Gare de Lyon) make sense.

Winton’s story racks up a lot of frequent flyer points: loveable knockabout Scully, an innocent Australian abroad, wants to fulfil his wife Jennifer’s desire to live in rural Ireland. He does up an old bothy while she goes back to Western Australia for a couple of months with their young daughter Billie to settle affairs. On the day of their return, however, only the child comes through the airport’s sliding doors, traumatised and unable – or unwilling – to explain what has happened to her mother en route.

The novel (written in pre-mobile phone era 1994) depends on arrangements by telegram and short, increasingly distrustful calls to former friends who all seem to be withholding information. Scully and Billie embark on a helter-skelter and increasingly penniless journey (care of Amex), to Hydra, Paris, Florence and Amsterdam, retracing the family’s recent journey and confronting a host of characters who may or may not hold the key to Jennifer’s vanishing.

How do you condense a 380-odd page novel into 90 minutes of sung storytelling? By picking out key images and phrases, says librettist Alison Croggon, and by remembering this is now a work of theatre. The rhythm of words is crucial and although her libretto was created before the score – “I wrote the first draft very quickly to get my initial reactions on paper” – she stresses it was a collaboration.

“I don’t just give him the libretto and send him off,” she says of composer Iain Grandage, who commissioned Croggon in 2012. The poet, novelist and theatre critic enjoys the strictures, the way Grandage asked her for very specific changes, the sudden demand for “another 10-syllable line that rhymes with beach”.

This is Croggon’s eighth libretto but her first adaptation of a full-length novel. Though daunting, it’s “logical” to write libretti if you write poetry, she says. Save for giving the project his initial blessing, Winton was not involved. The award-winning writer’s work has been adapted for TV, film and stage more often then any other living Australian novelist but he’s famously hands-off.

“I stopped thinking about it years ago,” Winton says of The Riders. “[Iain] came to me – what am I going to say except ‘why?’”. He wouldn’t have a clue how to adapt his own work for opera, he says, confessing that he finds the power of music frightening. “One of the miracles of music is its economy of emotion, but it’s dangerous; it’s freighted.”

Grandage gained Winton’s permission after writing the music for the stage version of Cloudstreet, the author’s best-known work. He also scored Winton’s first play, Rising Water and a section of the film, The Turning. Winton for his part says he admires Grandage for his musicianship, his “brinkmanship” and his eclectic taste.

The author’s lack of preciousness is fortunate; both Grandage and Croggon prefer to call the opera a reimagining rather than an adaptation and it’s fair to say that some major liberties have been taken with the novel’s plot, changes necessary for dramatic reasons, they both insist.

A major shift is the presence of Jennifer as a character rather than a cipher. It was an early decision – the haunting qualities of the book and the dangling question of her disappearance didn’t work on stage. “In the end, all our responses to Jennifer were that she needed to have more obvious motives; we wanted to answer some of these, ones that are left unanswered by the book,” says Grandage.

Croggon agrees: “We’re true to the emotional arc of the novel. It did bother me that Jennifer was merely an absence [in the novel] seen only through Scully’s eyes.” It’s very much a “bloke’s book”, she adds. Indeed, the book’s negative portrayal of most of the adult women has given rise to accusations of misogyny (a charge Winton trenchantly dismisses).

The abandoning of the child seems particularly callous, but, as Croggon says, where would half of literature be without cruel mothers?

A visit to rehearsals coincides with a run through of a climactic scene in Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral, building on a less dramatic scene in the book. The revolving stage is dominated by a series of wooden hurdles. These are transformed into a wide range of settings and even characters, including the enigmatic riders of the title, who may or may not be Celtic ghosts from Ireland’s turbulent past.

A co-production between Victorian Opera and Malthouse theatre, the artistic directors of both companies are running this show, Marion Potts as director (replacing Neil Armfield who who was originally attached) and Richard Mills as conductor.

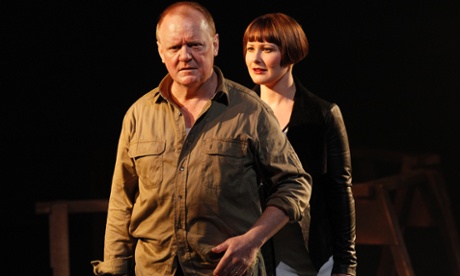

Orchestra Victoria’s soundscape is supplemented by bouzoukis, piano accordions and virtuoso soloist Genevieve Lacey on recorder. Baritone Barry Ryan, soprano Jessica Aszodi and mezzo-soprano Dimity Shepherd are principles in a very experienced cast, but finding the right juvenile for the daughter was harder. After Billie’s age was increased to 10, 17-year-old Isabela Calderon, a student at Wesley College and a member of VOs youth chorus was cast in the role.

Billie, says Potts, is “the emotional through-line” as Scully becomes increasingly infantilised. This is Potts’s first opera but she’s enjoying the experience especially, she says, the “high state of human emotion and opera’s capacity to span the intimate and the epic”. It’s Grandage’s first opera, too, although the classically-trained cellist has previously composed a range of material instrumental and vocal material alongside his work as a musical director and theatre collaborator.

As well as echoes of Schubert’s Erlkönig and Death and the Maiden, his score riffs on Irish and Greek folk music with snatches of Weimar cabaret. A recurring motif is a musical setting of Irishman Patrick Kavanagh’s lovelorn poem, Raglan Road, which Winton used to mark each section of the book.

The Riders differs from most of Winton’s output in that it isn’t set in his beloved WA. Even so, says Grandage: “it’s imbued with Australia. Its egalitarian ideals are in its bones.” He’s in awe of Winton’s ruthless portrayal of male fragility, “his ability to embody the everyman and capture the stunted emotional growth of the Australian male psyche.” And despite the drama of ceaseless travel, The Riders ultimately offers a very different form of transportation: “my opera speaks to the emotional trajectory of the novel, rather than its geography.”

• The Riders runs from 23 September to 4 October at Malthouse theatre, Melbourne