The reaction to the fire that ravaged the Glasgow School of Art earlier this year indicated how deeply architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh is loved. Yet at the onset of the first world war, Mackintosh was at a low ebb. Starved of commissions, he washed up like a piece of driftwood in the Suffolk coastal village of Walberswick, subsisting on his wife's inheritance and sporadic sales of botanical illustrations. It was a period in his career when Mackintosh might have been forgiven for thinking he couldn't get arrested – until the local constabulary did just that, keeping the artist in custody for two days on suspicion of being a German spy.

Esther Freud has a house in Walberswick, which she has written about once before in 2003's The Sea House. And while the story of Mackintosh's incarceration may seem almost too good to be true, it wasn't even an isolated incident. The paranoid suspicion aroused by the wartime Defence of the Realm Act ("See Everything, Hear Everything, Say Nothing") led to more than one artist facing charges of espionage. Sir John Lavery was arrested by over-zealous police officers for sketching the fleet in the Firth of Forth, even though he had been commissioned by the admiralty. The portraitist Philip de László was even unluckier – he was interned for two years, having been accused of signalling to a Zeppelin pilot with a cigarette lighter in Piccadilly Circus.

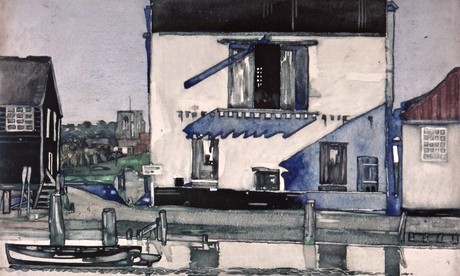

So what were the credulous fishing folk of Suffolk (whose shore was identified as the country's most vulnerable to invasion) to make of a tall, taciturn stranger with an incomprehensible accent whose work involved striding along the shore with his binoculars? Freud presents the reaction through the eyes of a child – Thomas Maggs, a publican's son, who has one lame leg and whose untutored talent for painting arouses the admiration and encouragement of the Scotsman – and Mackintosh's equally enigmatic, flame-haired artist wife, Margaret.

Thomas's perception amplifies the sense of adventure – to an 11-year-old boy the incomer even "looks for all the world like a detective. He's wearing a great black cape and a hat of felted wool, and he is puffing on a pipe as if he is Sherlock Holmes." And while the rest of the village mounts a whispering campaign about the stranger's motives, Thomas seeks out pictorial examples of his buildings ("I have my favourites now, the library in the School of Art with its soaring windows and its lamps") and concludes: "He may even have been sent here to keep us safe. Design our own fortress, with battlements and arrow slits, and a drawbridge that drops down to the beach."

In truth, Mackintosh had come to Suffolk to save money, paint and tend his wounded ego. The novel is lit up by flashes of his irascibility and sense of injustice; not least the lack of credit he received for the School of Art: "Not a mention of me in that whole damn building. Not in the heating ducts, or the double-hinged doors, not in the sculpture studio or the boardroom with its hanging lights – you know it is the first building in Glasgow to have electricity?" When his wife gently reminds him that commissions for Mrs Cranston's tea rooms are still forthcoming, he snaps: "Yes, and I'd rather be designing Liverpool cathedral."

Freud writes with sound local knowledge and a poet's ear for maritime lingo: "The boom, the block, the bailer, the clew and cleat and daggerboard." But the balance of the novel is enhanced by the fact that Mackintosh is not Thomas's only mentor. Equally significant is the character of George Allard, an elderly rope-maker whom Thomas assists in the ancient art of teasing hemp into twine. Like Mackintosh, Allard is a craftsman who believes that "everything that's worth anything comes from God's own ground" and that the war has "turned men on to unnatural things".

One emerges from the novel well versed in the rope-making lexicon of "strick", "dab" and "babbing string", but also realising that it is a vanishing art. Thomas tries to convince himself otherwise: "I want to say the world will soon turn back once the fighting's finished. But I've stood on the cliff path beside the strings of wire, and I know, because I've felt the jagged barbs, that this new rope will outlast us all." Freud's novel is a tantalisingly oblique portrait of Mackintosh in his declining years, but also a personal story placed at the fulcrum of the era when commercialism replaced craftsmanship.

• To order Mr Mac and Me for £13.59 with free UK p&p call Guardian book service on 0330 333 6846 or go to guardianbookshop.co.uk.