“To Luton falls the honour of knowing it was in on the start of a revolution,” announced the Luton News proudly in October 1959. The new decade was drawing nigh and soon there would be talk of revolution in homes and newspapers throughout Britain. But in Luton’s case the transformation was neither sexual nor political. Instead the journalist was celebrating the opening of 55 miles of the country’s first motorway, the M1. The swinging 60s were heralded here as in many other parts of the country by bulldozers, concrete and tarmac.

This revolution of the roads seems to have been one of the few aspects of progress that was greeted enthusiastically by the majority of British citizens. The country that emerges in this sixth instalment of David Kynaston’s mammoth, immersive history of postwar Britain is strikingly reactionary, rendering the “modernity” of Kynaston’s title almost ironic.

In the face of chronic housing shortages, the authorities were building high-rises, many of them defiantly modern. “The future is bright,” proclaimed the architect Basil Spence in 1960, celebrating modern architecture for looking “straight into the future, not backwards”. But most families were reluctant to become “prisoners in the sky”, even when it offered the chance to escape cramped and dilapidated homes. “The stay-putters are one of our biggest problems,” complained the city architect in Liverpool, unable to convince slum-dwellers to embrace modernity.

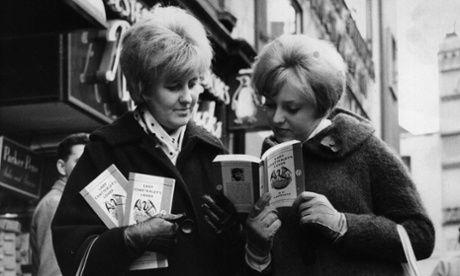

Nor were the British natural revolutionaries when it came to sex. In 1961, the contraceptive pill was introduced, but Kynaston’s diarists were on the whole more excited by the advent of ready-salted crisps, plastic carrier bags and the automatic dishwasher than the possibility of free love. Except, that is, when the love was literary. Two million copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover were sold within a year after Penguin won the legal case to publish the unexpurgated version in November 1960.

For two weeks, literary critics and clergymen had defended DH Lawrence’s literary merit against charges of corrupting obscenity. According to the Bishop of Woolwich, Lawrence portrayed sex as “in a real sense an act of communion”. For Richard Hoggart, the novel was “highly virtuous and if anything, puritanical”, despite the 13 explicit sexual episodes detailed by the prosecuting lawyer, who warned the jury of the dangers of their wives or servants reading the book.

When the judge ruled in Penguin’s favour, Lawrence’s stepdaughter felt as though “a window has been opened and fresh air has blown right through England”. But though the novel became an instant bestseller, few readers were convinced by Lawrence’s plea for sexual freedom. The jury was given a week to read Lawrence’s 300-page book yet Margaret Thatcher (recently installed as the MP in Finchley) read it in three hours and 20 minutes. She found that it did indeed “offend against most of the ordinary standards of public taste” and many of her constituents shared her views.

The Chatterley trial is one of several episodes that Kynaston covers at length, allowing stories to emerge in more detail than in the first volume of Modernity Britain where the pace was sometimes too breathless to be engaging. It makes this volume an exciting read, containing moments of suspense and lengthy sections of analysis. There are intelligent, well synthesised accounts of the nationalisation debates, slum clearance, the emergence of the new left and its fraught relationship with the Labour party, and the changing position of women (“I say a wife can do two jobs,” said Margaret Thatcher helpfully in 1960).

The society that emerges is one that comes worryingly to mirror our own, both in its so-called modernity and its reactionary insularity. This was the era when citizens first identified themselves wholeheartedly as consumers, embracing self-service department stores and hire purchase credit. Surveying the new Marks & Spencer, Philip Larkin half-admiringly described “the large cool store selling cheap clothes/Set out in simple sizes plainly”. More bitterly Raymond Williams complained that more was spent on advertising a new soap than on supporting an orchestra. This seems unremarkable to us now.

More disturbingly, we can recognise our own times in some of the most embarrassing moments of insularity. We may no longer be able to envisage a West End musical containing the song I’m Golly, I’m Woggy, I’m Nigger but it is not all that hard to imagine the race riots. A 1962 poll revealing that 71% of those surveyed thought that immigrants to this country were “doing too well at the expense of the British people” sounds uneasily familiar, even if it now seems shocking that only two in five wanted the British to vote against South African apartheid at the UN in 1961. It is harder to be surprised by the news that less than one in two supported Britain’s application to join the common market in 1961. For these tidings alone Kynaston’s book makes salutary and urgent reading, suggesting that we might do well to live with half an eye on the Kynastons of the future.

And thankfully the grimmer moments come interspersed with Kynaston’s trademark juxtapositions and revealing details. Culturally, modernity is glimpsed lurking in corners, ready to pounce. We see Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell being imprisoned for stealing and defacing more than 70 books from north London public libraries, mocked by the judge as embittered would-be writers. David Hockney is identified in the Times as the “star turn” of his year at art school and Leonard Cohen buys his not-yet-famous blue raincoat at Burberry’s.

Lara Feigel is the author of The Love-charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (Bloomsbury).