"If it is a trickle of sad phrases it is because I am sad and tired and coming to an end, don't talk to me for God's sake about the duty of happiness, do you want me to put on a black moustache and pad out my cheeks with cotton wool, I'll be very glad if you come over and do all I can and enjoy doing it to give you at least a little of what you want."

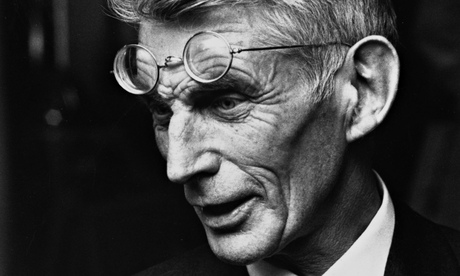

When he wrote this remarkable sentence, in March 1960, Samuel Beckett, supposedly "coming to an end", had nearly 30 more years to live. They would be spent in close company with the woman to whom he was writing here, Barbara Bray, who at this moment was considering quitting London with her young daughters to move to Paris where Beckett had been resident since before the war. The two had become acquainted while working together on Beckett's first radio play, All That Fall, written for the BBC Radio Third Programme; Bray was a script editor there, where she also commissioned and translated many innovative French and Italian writers, such as Marguerite Duras, Robert Pinget, Jean Genet and Luigi Pirandello. Within two years of meeting, Bray had become not just intimate with Beckett, but almost indispensable to him and of invaluable assistance to his work.

Nearly 20 years Beckett's junior, Bray had studied at Cambridge, after which she married then moved to Egypt to teach English literature. When she returned to Britain and began working for the BBC, she was estranged from her husband (who died in an accident at the time she was getting to know Beckett). Bray was attractive, confident, cultured and an excellent linguist. She did not hesitate to instruct her companion on what he should be reading; he did not hesitate to share with her, with a frankness and openness not ventured with anyone before, the details of whatever work was in progress (or in regress, as he often felt it to be) – it amounted to more than 700 letters by the end. Bray did move to Paris with her daughters, despite the lukewarm encouragement she received, at which point Beckett chose to marry his long-term partner Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil (the ensuing tension is often seen to be the key to his play entitled Play, written shortly after). The one time I met her, at a celebration of her 70th birthday, Bray was glamorous, witty, sharp, entertaining her admirers with anecdotes about how unsuccessful she had been in trying to curb Duras's excesses. When I dared ask her if Beckett had ever talked to her of his letters and what would become of them, she confided that "Sam always told me he didn't give a damn who read them, so long as he was dead."

When he learned that Bray had been widowed, in May 1958, Beckett sent her one of the most moving and beautiful of his "mourning letters" – a genre in which he was already a past‑master. "All I could say," he wrote,"and much more, and much better, you will have said to yourself long ago. And I have so little light and wisdom in me, when it comes to such disaster, that I can see nothing for us but the old earth turning onward and time feasting on our suffering along with the rest." His letter offers consolation, even as it recognises a fundamental and unavoidable inconsolability. "Somewhere at the heart of the gales of grief (and of love too, I've been told) already they have blown themselves out. I was always grateful for that humiliating consciousness and it was always there I huddled, in the innermost place of human frailty and lowliness." It may be hard, with the benefit of hindsight, not to think of the next long play Beckett would write, commencing just two years later, and of its title, when reading the words with which he closed his letter: "Work your head off and sleep at any price and leave the rest to the stream, to carry now away and bring you your other happy days."

One of the problems facing Beckett during the period covered by the third volume of his letters was that, given the huge and still growing international popularity his work was enjoying, it had become increasingly hard for him plausibly to promote his aesthetic of indigence and failure. He knew he had to find fresh and innovative ways to express his lack of belief in what the world called "success". With Bray he could be frank, certain she would understand him, about the nostalgia he felt for a time when he was practically unknown, impoverished, with no prospect of ever finding a public. "I am in acute crisis about my work," he wrote in 1958, not long after Endgame had premiered in English, "(on the lines familiar to you by now) and have decided that I not merely can't but won't go on as I have been going more or less ever since the Textes pour Rien and must either get back to nothing again and the bottom of all the hills again like before Molloy or else call it a day".

The new work that would emerge from the determination signalled here was the formidably difficult novel Comment c'est (How It Is). Yet even as he worked at it, he did not in fact retreat completely from the world, and when he was in Paris, a "reasonable" night was one that saw him home before dawn and able to recollect, the following morning, where he had parked his Citroën 2CV car. On a morning after what was clearly a less than reasonable night, he wrote a letter to Bray that was as freewheeling as anything he ever wrote in English (where the brakes tended to be on – more than when he wrote in French). "Still drunk this morning after sudden hopeless useless midnight bucket of brandy and sitting in special ever since 37 pub and have yours to hand and in head grinding old poem in vain by Hölderlin influenced entitled Dieppe circa 37 … "

This opening sentence rattles on for another dozen lines.

The radio play that brought Beckett and Bray together is the most explicitly Irish of his mature works, set around a railway station in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock (renamed "Boghill"). It is this childhood world that surges forth, as he continues his letter, "full of memories, cricket unexpectedly with brother's huge bat, hardly lift it, loss of railway ticket, fear of whiskered porter, walk home devious ways 10 miles, huge bag, father rampaging on Mrs Rooney's road, mother in furious swoon, police alerted in vain, midnight, foodless to bed … part of boyhood, heroic days". Never losing sight for long of the work in progress, without a pause for breath he returns to it: "Work no good, hammer hammer adamantine words, house inedible, hollow bricks, small old slates from demolished castle, second hand, couvreur fell off backward leaning scaffolding and burst, fat old man, instantaneous the things one has seen and not looked away."

In Bray, Beckett had found a companion, an interlocutor, a peer, with whom he could – and he did in letter after letter – "hammer hammer" his "adamantine words".

Dan Gunn is one of the editors of The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume 3, 1957-1965, which is published by Cambridge.