Towards the end of this book, Grayson Perry notes that the moment he decided to be an artist was the exactly the same moment that he felt pressurised to put away childish things. "I found myself alone with a box of my brother's toy cars," he recalls, "and usually I used to lose myself for hours narrating car races and dogfights under my breath. But that day I picked up one of the cars and realised I could no longer lose myself. Self-consciousness had crept in; a pall of embarrassment cast a shadow, like the Wicked Witch of the West, across my imaginary landscape."

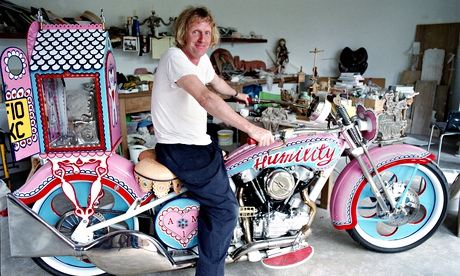

Perry delayed this shift from innocence to experience longer than most: one of the more surprising facts about his recollection of that moment is that it occurred when he was 16 years old. It would, even then, be fair to argue he did not give up on that sense of boyish total immersion without a struggle. As soon as Dinky cars denied him some of their magic, the artist found new worlds to lose himself in. He started to go out at night in Chelmsford in an early incarnation of his (or alter ego "Claire's") singular dressing-up box style; he became a dedicated biker, latterly on a pink Harley-Davidson that doubled as a shrine to his totemic teddy bear, Alan Measles. And, of course, the nation's favourite transvestite potter eventually found a revised set of co-ordinates for his imaginary landscape in lumps of clay.

If Perry's Playing to the Gallery, a tidied up version of last year's Reith lectures, has a theme, it would be to make a case against embarrassment of all kinds when it comes to art. That is, against the embarrassment of looking or of liking, of self-expression or self-absorption. The book is, in this sense, a kind of manifesto. Most artist's manifestos – implicitly or explicitly – are a statement of taste. However objective or scientific they appear, they are there to tell you what is good art and what is not; what you should appreciate and what you shouldn't (manifesto-writer's subtext: look at my stuff, not his or hers). This isn't really that kind of manifesto at all, it's rather a polemic for inclusivity. "I firmly believe," Perry states at the beginning, "that anyone is eligible to enjoy art or become an artist – any oik, any prole, any citizen who has a vision they want to share."

You have, no doubt, read that sentiment elsewhere – it is after all, the mantra of "the art world", however cool the welcome that is actually extended. The great thing about Perry's statement of it here is that you are always convinced that he believes it and lives by it. His "come on in, the water's lovely!" spirit is an argument certainly for lightness and for play, but also for a different kind of rigour and commitment.

Part of the commitment Perry argues for, tentatively, and with qualification, is a commitment to making (his memorable 2011 British Museum show, The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, was perhaps an even more coherent statement of his thinking than the one he presents here). There are plenty of ideas in his art, but the one he adheres most passionately to is that old-fashioned one of "art as a visual medium, usually made by the artist's hand, which is a pleasure to make, to look at and to show to others". He is too generous a thinker to draw the line there, as it were, but along the way he expresses some amusing disquiet about the kind of conceptual art that is "luxurious in its finishes, accessible in its imagery, and mind-boggling in its prices", about art that wants to be an asset class, about art that, by default, is made by the 0.01% for the 0.001%.

One way to counter that sense of art only as business is through jokes, not least the one involving the cross-dresser pointing out the emperor's lack of clothes. Perry has plenty of others, little visual gags that include his "art quality gauge", a card to be held in front of a piece of art with the question: "Which location would it look most at home in?" and a scale of possibilities that ranges from "Mum's back bedroom" through "roundabout in Milton Keynes" to "Elton John's lawn" and "Tate".

There is in all of this, as he emphasises, no right answer; the thing is to ask the right questions, and maybe follow a few simple rules for ways of seeing. My favourite is one he nicked from Alan Bennett who, as a trustee of the National Gallery, argued for a big sign outside that read simply: "YOU DON'T HAVE TO LIKE IT ALL."