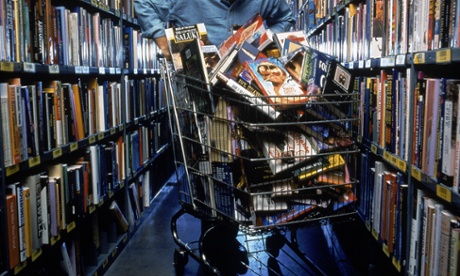

When I get new books, I like to share them with people. Unfortunately, since you all are so far away, I cannot host a book party in my crib where you can look over them, so I’ll do the next best thing. I’ll host a book party on my blog each Friday of the week when I either purchase books, they are given to me or when review copies arrive in the mail. In this New Books Party, I will try to be your eyes by presenting my quick “first impression” -- almost as if we are browsing the shelves in a bookstore together -- and I’ll also provide relevant videos about the book and links so you can get a copy of your own.

Books that arrived recently:

Hormones: A Very Short Introduction by Martin Luck [Oxford University Press, 2014; Guardian bookshop; Amazon UK; Amazon US/kindle US]

Publisher’s synopsis: Hormones play an integral part in the balance and workings of the body. While many people are broadly aware of their existence, there are many misconceptions and few are aware of the nature and importance of the endocrine system.

In this Very Short Introduction, Martin Luck explains what hormones are, what they do, where they come from, and how they work. He explains how the endocrine system operates, highlighting the importance of hormones in the regulation of water and salt in the body, how they affect reproduction and our appetites, and how they help us adjust to different environments, such as travel across time zones.

In this fresh and modern treatment, Luck also touches on the ethical and moral issues surrounding research methods, testing on animals, and hormone misuse.

My first impression: A large part of my dissertation work focused on the relationship between steroid hormones, their receptors and the resulting behaviour in songbirds, so one could argue that hormones are important to me. But throughout the course of my studies, I was always surprised by how little most people knew, or understood, about something that is as commonly mentioned as hormones. But this little book presents an informative and readable overview to the subject, naming the different types of hormones, their physiological effects, and the ethics of hormone use and abuse. It also includes a number of useful diagrams. I was somewhat disappointed that there was only a tiny section about the evolution of hormones -- a fascinating topic! -- but this is due to my own interests rather than any sort of glossing over by the author: he has a complex and interesting topic to cover with a minimum of words! As with all titles in the Very Short Introduction series, all this information is neatly organised within a small paperback that fits into a coat pocket, bag or rucksack so you can pull it out and read it anywhere.

Actual Consciousness by Ted Honderich [Oxford University Press, 2014; Guardian bookshop; Amazon UK; Amazon US]

Publisher’s synopsis: What is it for you to be conscious? There is no agreement whatever in philosophy or science: it has remained a hard problem, a mystery. Is this partly or mainly owed to the existing theories not even having the same subject, not answering the same question? In Actual Consciousness, Ted Honderich sets out to supersede dualisms, objective physicalisms, abstract functionalism, general externalisms, and other positions in the debate. He argues that the theory of Actualism, right or wrong, is unprecedented, in nine ways:

- It begins from gathered data and proceeds to an adequate initial clarification of consciousness in the primary ordinary sense. This consciousness is summed up as something’s being actual.

- Like basic science, Actualism proceeds from this metaphorical or figurative beginning to what is wholly literal and explicit—constructed answers to the questions of what is actual and what it is for it to be actual.

- In so doing, the theory respects the differences of consciousness within perception, consciousness that is thinking in a generic sense, and consciousness that is generic wanting.

- What is actual with your perceptual consciousness is a part or stage of a subjective physical world out there, very likely a room, a world differently real from the objective physical world, that other division of the physical world.

- What it is for the myriad subjective physical worlds to be actual is for them to be subjectively physical, which is exhaustively characterised.

- What is actual with cognitive and affective consciousness is affirmed or valued representations. The representations being actual, which is essential to their nature, is their being differently subjectively physical from the subjective physical worlds.

- Actualism, naturally enough when you think of it, but unlike any other existing general theory of consciousness, is thus externalist with perceptual consciousness but internalist with respect to cognitive and affective consciousness.

- It satisfies rigorous criteria got from examination of the failures of the existing theories. In particular, it explains the role of subjectivity in thinking about consciousness, including a special subjectivity that is individuality.

- Philosophers and scientists have regularly said that thinking about consciousness requires just giving up the old stuff and starting again. Actualism does this. Science is served by this main line philosophy, which is concentration on the logic of ordinary intelligence—clarity, consistency and validity, completeness, generality.

My first impression: This is a philosophical exploration of consciousness. Meticulously researched and extensively cited, the writing is very precise and typically academic. This means that most people may find the book slow going, unless they’ve got a passionate interest in the subject. However, that said, this is one of the few books ever published that explores this topic in depth.

Animal Madness: How Anxious Dogs, Compulsive Parrots, and Elephants in Recovery Help Us Understand Ourselves by Laurel Braitman [Simon & Schuster, 2014; Guardian bookshop; Amazon UK/kindle UK; Amazon US/kindle US/audible US]

Publisher’s synopsis: Science historian Laurel Braitman draws on evidence from across the world to show, for the first time, how astonishingly similar humans and other animals are when it comes to their emotional wellbeing. Charles Darwin developed his evolutionary theories by studying Galapagos finches and fancy pigeons; Alfred Russel Wallace investigated creatures in the Malay Archipelago. Laurel Braitman got her lessons closer to home -- by watching her dog. Oliver snapped at flies that only he could see, suffered from debilitating separation anxiety, was prone to aggression, and may even have attempted suicide. Braitman’s experiences with Oliver made her acknowledge a startling connection: non-human animals can lose their minds. And when they do, it often looks a lot like human mental illness. Thankfully, all of us can heal. Braitman spent three years travelling the world in search of emotionally disturbed animals and the people who care for them, finding numerous stories of recovery: parrots that learn how to stop plucking their feathers, dogs that cease licking their tails raw, polar bears that stop swimming in compulsive circles, and great apes that benefit from the help of human psychiatrists. How do these animals recover? The same way we do: with love, medicine, and above all, the knowledge that someone understands why we suffer and what can make us feel better.

My first impression: I’ve been reading and listening to podcast interviews with the author for the past couple weeks so of course, I HAD to get a copy of this book. I read chapter four, “If Juliet were a parrot”, which explored self-destructive behaviour and suicide. Although the book is interesting, carefully researched and readable, the author makes numerous forays into the possibility that animals have complex emotional states -- such as planning future actions -- that I have trouble accepting as valid. This is not to say that I don’t believe animals have emotional states, because I think they do, but I don’t accept that animals have advanced reasoning abilities that stem from basic emotional states. Needless to say, this book will be fascinating reading and will generate lots of conversation for years to come.

The Horse: 30,000 Years of the Horse in Art by Tamsin Pickeral [Merrell Publishers, 2009; Guardian bookshop; Amazon UK; Amazon US]

Publisher’s synopsis: Of all man’s fellow-creatures, the horse, with its inherent grace, intelligence and courage, has inspired the strongest feelings of empathy an affinity reflected in more than 30,000 years of artistic representation. This unabridged compact edition of Tamsin Pickeral’s stunning history of the horse in art documents the creative journey from prehistoric cave painting to the war horses of Uccello, the elegant portraits of Stubbs and the enigmatic prints of Elisabeth Frink. Profusely illustrated throughout, the book sheds particular light on man’s relationship with the horse, and on the story of equine evolution from the stocky primitive to today’s glamorous thoroughbred.

My first impression: I admit that I am a total sucker for horses -- always have been and probably always will be -- and I recently purchased this book whilst visiting the National Gallery in London. Printed on glossy art paper, the full-colour reproductions of artwork are stunning and the author includes enough history about each piece that it will satisfy art-lovers and art historians too. Enthralled, I couldn’t put the book down once I’d opened it at the Gallery bookshop, so one could say that I didn’t choose to purchase it but rather, it chose to follow me home.

Parrot Culture: Our 2500-Year-Long Fascination with the World’s Most Talkative Bird by Bruce Thomas Boehrer [University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004; Amazon UK; Amazon US]

Publisher’s synopsis: After completing his conquest of the Persian empire, Alexander the Great maneuvered his army across the Hindu Kush and into India. During his two years there, he traveled from dry frigid mountains to humid tropical lowlands and then back across one of the most punishing deserts on the planet. He fought a series of desperate battles against strange foes mounted on war-elephants, suffering wounds that nearly killed him. And when he eventually turned homeward, he brought with him specimens of a rare, magical species, a bird that could speak with a human voice.

Introduced to Europe by Alexander, parrots were quickly embraced by Western culture as exotic and astonishing, full of marvelous powers, and close to the gods. Over the centuries they would become objects of veneration or figures of folly, creatures prized for their wit—or their place on the dinner table. Ultimately, they would become emblematic of the West’s interaction with the world at large. Identifying a deeply rooted obsession with these beautiful and loquacious birds, Bruce Thomas Boehrer provides the first account of parrots and their impact on the Western world.

Parrot Culture: Our 2500-Year-Long Fascination with the World’s Most Talkative Bird traces the unusual history of parrots from their introduction in the Graeco-Roman world as items of oriental luxury, through the great age of New World exploration, to the contemporary ecological crisis of globalism. Boehrer identifies the poignant irony in the way parrots became ubiquitous as symbols and mascots, while suffering near extinction at the hands of those who desired them. Exploring their presence and meanings in the art, literature, and history of Western civilization, Parrot Culture also celebrates the beauty, intelligence, and personality of these birds, whose fate will say as much about us and the world we have created as it will about them.

My first impression: written by a professor of literature who is a companion parrot-person, this book examines the cultural and personal impact of parrots through history. The author quotes poetry and passages from literature, and includes quite a few black-and-white reproductions of paintings, drawings, and photographs of parrots and their people. (I admit; I wish these illustrations were in colour.)

Itchcraft by Simon Mayo [Publisher, 2014; [Doubleday Childrens, 2014; Guardian bookshop; Amazon UK; kindle US]

Publisher’s synopsis: Exploding euros and exciting elements - join Itch, Jack and Chloe on their latest adventure.

Itchingham Lofte, teenage element hunter and unlikely hero, has had enough excitement to last him a lifetime. Stumbling across an unknown radioactive element and trying to keep it out of the hands of those who want to use it for their own ends was hard enough. But when a school trip to Spain ends in exploding currency and rioting locals, he knows that he has to continue to look for answers.

Itch knows the lives of those closest to him are at risk. He must track down a deadly enemy who will stop at nothing to take his vengeance . . .

My first impression: Third in a series of books about a teen-aged element hunter, this book looks like it is the best yet, although I’ve only been able to briefly skim it. Despite this being a children’s book, it certainly appeals to adults, too. For example, the moment my spouse saw the book, he stole it from me and hid in the bedroom, reading. This alone should tell you something about it!

What book(s) are you reading? How far are you along in the book? What do you think of it so far? Do you think your book is worth recommending to others?

.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

When she’s not reading a book, GrrlScientist can also be found here: Maniraptora. She’s very active on twitter @GrrlScientist and sometimes lurks on social media: facebook, G+, LinkedIn, and Pinterest.