Invisible: The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen by Philip Ball is the kind of book I really enjoy. For one thing, the writing is crisp and often witty (a virtue not as common as it should be among nonfiction works). For another it is packed with abstruse information. Most crucially, Ball's extensive research, rather than being a parade of intellectual swank, works to encourage connections and make the reader think, another experience that is rarer than it might be.

As the title suggests (I could do without the overdramatic subtitle) his topic is the invisible, which, it turns out, has a long and venerable role to play in the story of human civilisation.

He starts with story, where, as all children know, the invisible is a key presence – or non-presence, I should say. The notion that true power resides in an invisible world is not only the stuff of myth and fairytale but also the basis of all known religions. And the search for power beyond the everyday, he surmises, is one major factor in our fascination with the invisible.

This idea leads in any number of fertile directions. Among the book's strengths is its discussion of psychology. For example, Ball quotes the well documented fact that up to the age of four children become "invisible" by simply closing their eyes. However, this piece of seemingly innocent irrationality turns out to be "an epistemologically complex statement", for experiments with two- to four-year-old children reveal that a child does not suppose you cannot see her head, or her feet, for example, but only that "she" cannot be seen. The essential "she" or "he" turns out to be distinct from the child's body. "Further testing suggested that, for children, the act of seeing a person – which is to say knowing about the person's presence – depends on a mutuality of gaze: the child believes that only when an observer locks eyes with her can he register her actuality." Ball's conclusion from this is typically thoughtful: "We're left thinking not how a child can be so foolish as to imagine they disappear just by closing their eyes but rather, how extraordinary it is that the self is not located from birth in the body." Surely this has something significant to contribute to the whole mind/body question and the locus of consciousness. (It is worth adding, as he points out, with a reference to my childhood favourite, The Borrowers, that to be "seen" is not always desirable:

"Pod looked at her blankly. 'I been "seen",' he said.

… Homily stared at the table. After a while she raised her white face. 'Badly?' she asked.

Pod moved restlessly. 'I been "seen". Ain't that bad enough?'")

The most flamboyant, though by no means the most interesting, sections of the book concern bizarre occult methods for attaining invisibility. Eyes of an ape or an owl (the latter to be dug out of the live bird), beetle dung, the head of a suicide stuffed with fava beans, the heart of a bat, the bones of a cat boiled alive are some of the ingredients which must be handled according to such complex instructions that they were surely devised with an eye to explaining the inevitable failure to deliver. The often heartless nature of these recipes conveys the close connection between the pursuit of invisibility and the so-called black arts. Ball argues (not entirely persuasively) that the wish to be invisible is essentially a wish for power, since if you are invisible you cannot be held to account. He cites fabled examples of this, including Plato's tale of Gyges's Ring, whose eponymous owner was able to steal undetected a queen and thus a kingdom through its power. As Plato's Glaucon suggests: "No man would keep his hands off what was not his own if he could safely take it."

This book is not only a delightful compendium of arcane facts and clever quotes. Ball's sharp comments are good value too. "Invisibility provides access to liminal places, tinged with desire, allure and possibility. Such allegorical content means that magical invisibility in fiction should never function as a convenient power that advances the narrative. That is why the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings supplies a more satisfying, more mythically valid emblem than the cloak of invisibility in the Harry Potter series… Magic must not be incidental or mundane." Too right!

Assisted by rich reference to literature, history and philosophy, Ball, who is a science writer, explores the interplay between "natural magic", espoused by such scientific luminaries as Isaac Newton, and modern science. Very often, as in Newton's case, the two classes of belief were held simultaneously. In other cases, as with William Crookes, scientific discovery was employed to foster belief in the paranormal. James Clerk Maxwell, when sent an 1875 paper by Crookes, endorsed it for publication and Crookes stole from Michael Faraday in order to promote his idea of "radiant matter" as a psychic force. Literature, too, made connections between invisible rays and the paranormal. Rudyard Kipling believed we were receptors who could receive messages from eternity via the ether, an idea illustrated in his story Wireless, where a consumptive young man picks up lines of poetry from the dead Keats.

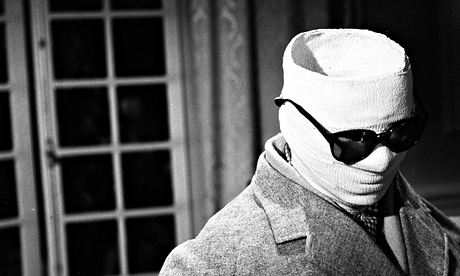

All of which leads to the rather disquieting present day, where far from eschewing the mythic and magical, advanced technologies address the production of work on shields of invisibility. As Ball says, magic, rather than being the antithesis of science, has becomes its inspiration. While the invisibility of HG Wells's Invisible Man is possible in principle but not in practice, it seems that work is even now afoot on the invention of "an artificial ether for carrying light, governed by rules that the scientists themselves may prescribe… The philosophy of metamaterials is to say that if nature does not provide atoms that behave in the way we require then we shall make them."

For a non-scientist this is a disturbing prospect and the clear-sighted Ball makes some shrewd observations about the dangers in such an prospect. I liked many things about this book but perhaps what I liked best was his summing up: "As the history of invisibility shows, myth is no blueprint for the engineer. It is more important than that."

Salley Vickers's new collection of short stories, The Boy Who Could See Death and Other Stories, will be published by Viking Penguin early next year. To buy Invisible: The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen for £18.99 with free UK p&p call 0330 333 6846 or go to guardianbookshop.co.uk