In 2002, a friend who told us he worked in the foreign office (we all suspected that he was really a spy) brought me a cricket bat back from a trip to Pakistan. Over the following two seasons I enjoyed a coruscating run of form (never rekindled) and felt I'd channelled down the years the glamour and excitement that was once synonymous with Pakistani cricket.

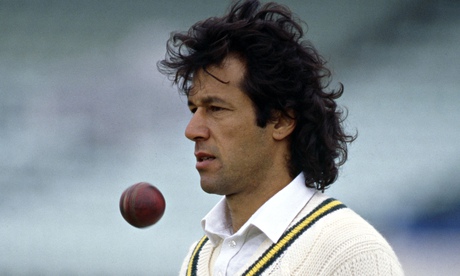

For those of us who came of cricketing age in the 1980s and 90s, when we'd watch the lithe, loping figures of Imran Khan and Wasim Akram race through opposition innings, the raw batting power of Inzamam-ul-Haq or the wilier gifts of Javed Miandad, Pakistan was the home of cricketing genius. As I read Peter Oborne's intelligent, detailed and highly affectionate history of the Pakistani game, Wounded Tiger, I was reminded of how far the team has fallen in subsequent years. Much of this decline, of course, is to do with things external to cricket – the "war on terror", the corruption of Pervez Musharraf's regime, the breakdown of civil society in a country seemingly under attack from all sides. What Oborne reminds us (at least in the early chapters of his book) is that this wasn't always the case. In the first years of post-partition Pakistani cricket, even while the country lurched from crisis to crisis, with war an ever-present threat, the sport remained a vehicle for hope, a magnet for decency and national feeling. Wounded Tiger is peppered with stories of cricketers, politicians and administrators working to better relations between Pakistan and India, to dampen radicalism, to make the sport the centre of a national narrative of patient progress.

Pakistani cricket has been through any number of dips and troughs since the violent partition of 1947, and Oborne charts all of them in his exhaustive account. He not only provides records of the vast majority of tests (including the painfully tedious matches in the 1960s when the Pakistani side attempted to out-bore their opposition), but also delves into the history of the pre-partition sport in Lahore and – in what is unfortunately the driest chapter of the book – the women's game in Pakistan. Oborne's last cricket book, which told the extraordinary story of Basil D'Oliveira, the mixed-race South African who played for England during the years of apartheid, was exquisitely researched and a scintillating read. It also had the chronology of its subject's life to shape the plot. Marshalling the turbulent history of the rise and fall of Pakistani cricket into a single narrative is a more difficult task.

Oborne succeeds when he focuses on the human beings behind the white flannels. His portraits of two of the early heroes of Pakistani cricket, AH Kardar and Fazal Mahmood, fizz with energy and life. Kardar is a snob in Jermyn Street suits who "prided himself, sometimes to the point of absurdity, on his Oxford education", and handed players staying with him wads of banknotes with which they might tip the staff. The blue-eyed Fazal is a more sympathetic character, who, when travelling through India to Bombay immediately after partition, was set upon by Hindu fanatics. Oborne tells us that they "would have lynched him but for the intervention of his travelling companion, the India cricket legend CK Nayudu, who defended Fazal against assailants with a cricket bat."

The early sections of the book are filled with such Boy's Own stories of heroism on and off the cricket field, and it is here that the Kipling-quoting Oborne is at his most comfortable, bringing in evocative figures like the Nawab of Pataudi and the Maharajkumar of Vizianagram, early aristocratic proponents of the game. In these early chapters, politics and sport interlace so neatly that Wounded Tiger becomes not so much a history of Pakistani cricket as a history of Pakistan viewed through the magnifying lens of the sport. The story of the first Pakistani tour of India, victory at the Oval in 1954, the English kidnap of a Pakistani umpire in 1956 ("Just Banter, Old Boy" was the exculpating headline in Time magazine), all of these are told with such verve, such a mixture of charm and wit, that we forgive Oborne his occasional lapses into cricketing journalese (different players are described as being "all at sea" within a couple of pages of each other; the near-identical rendering of innings after innings can feel bludgeoning at times).

The book wanders a little in its middle parts (much as Pakistan's cricket team did) and only finds its feet again with the coming of another (pseudo-) aristocratic figure, Imran Khan. The last section of the book – "The Age of Isolation" – attempts to find optimism in the game's current post-9/11 trough, and the author's lonely travels within Pakistan give the final chapters an elegiac, almost tragic air. Oborne finishes with an interview with Khan, linking him to his 1950s precursor, another handsome Oxford man, AH Kardar. It's a neat ending to an encyclopaedic but often thrilling portrait of a beautiful country and its place in the history of this most beautiful game.