In his 1967 novel, Gargoyles, the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard has the following passage: "Why suicide? We search for reasons, causes, and so on … We follow the course of the life he has now so suddenly terminated as far back as we can. For days we are preoccupied with the question: Why suicide? We recollect details. And yet we must say that everything in the suicide's life … is part of the cause, the reason, for his suicide."

In many ways, Munich Airport is a meditation on this passage of Bernhard. The novel tells the story of the impact of Miriam's suicide through anorexia on her (nameless) brother, the protagonist, and her father. The two are stranded at Munich airport waiting for the weather to clear in order to fly her body home to the States. (Miriam has been living estranged from them in Germany.) Father and son are both now also turning away from food – and the agony of their departure-lounge delay frames an account of the three weeks they have spent in Germany waiting for her body to be released. Interspersed with this are recollections of details of the past life of the protagonist and his family. They search their memories of Miriam's childhood and yet can find nothing, "or at least nothing so spectacularly out of the ordinary as to explain her suicide".

The Bernhard Museum is only two hours down the road from Munich airport and close reading reveals that Baxter, an American who lives in Germany, is engaged with Bernhard throughout. Here is Bernhard: "All my life I have had the utmost admiration for suicides. I have always considered them superior to me in every way." And here is Baxter's protagonist on his sister: "Our faith that she would one day need us again, just as we needed her, no doubt belonged to the hedonism and extravagance and stupidity of life above the pain of starving."

This rich and profound book is full of philosophical ideas and stark, ascetic beauty. There are no speech marks. The past and present interleave with one another in long blocky paragraphs without chapters or line breaks (as in Bernhard). The writing is scrupulous and often superb. Plot backs blushingly away and, instead, we are sifting deep into the archaeology of character in order to try to see existence itself.

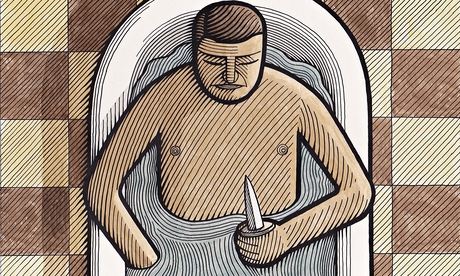

Yes, this is a good old-fashioned existential angst novel updated via the twin themes of starvation and satiety, fasting and bingeing. There are echoes of Sartre and Camus (as there are in Bernhard). Miriam's brother feels himself "fattening – expanding with habits, ideas, opinions, things … a plague of superabundance and anxiety". Dolores, another anorexic, merely smiles and looks a little sad, "as though nothing could be done, as though no amount of sympathy or concern of analysis could make the world more appetising". Later on the brother wounds himself with a knife in the bath in the hope that "I might, for a moment, before the pain becomes unbearable, witness the reality of the life of my body and by witnessing that reality, eliminate the mystery of who I am and how and what I perceive …"

These are Sartre's concerns – as is the idea that there is no such thing as a true story, or rather that our story is really the collection of the stories by which we misunderstand ourselves. Likewise, Baxter recapitulates Camus (in The Myth of Sisyphus), who talks of the clash between the human need for meaning and the fact that meaning is not pre-inscribed in the world. Bernhard again: "Everything is what it is, that's all."

I relished Munich Airport because it made me think deeply about the greatest subject of all, fiction itself. It is a serious and intense book that unflinchingly scrutinises what Baxter calls the "exotic-ordinary". And so my criticism is not of the writing or of the novel, but of the aesthetics. I simply don't believe in the stern fictional "authenticity" that Bernhard and Baxter peddle. Here is Bernhard in Gathering Evidence: "Only the most shameless writer is authentic." Here is Baxter's protagonist: "My father once wrote, in a review of a book about the holocaust … that the author … forgot to strap his shame down, and that he had therefore produced a book of gesticulations, a rather stylish book."

I find the austerity of these ideas to be a humourless posture. Surely all writers are forever in the business of what this book dismisses as "flourish, lyricism, hyperbole, opinion" - even when they are doing their very best to pretend otherwise? Surely we know by now that the clear-as-a-mountain-creek style and the coruscatingly honest protagonist represent the greatest artistic subterfuge of all?

Further, there's so much contempt, disgust, loathing, nausea and covert proselytising in this tradition of writing, which I find indicative of something else: a wound. And it's a wound that can best be understood in terms of psychology and motive, which Baxter, Bernhard and the gang so rigidly disavow. But, as I say, these are philosophical and aesthetical discussions that this fine book occasions, not criticisms of the work itself. And I wholeheartedly recommend Munich Airport to everyone interested in the ongoing and fascinating human conversation that is first-rate fiction.

• Ed Docx's latest novel is The Devil's Garden (Picador). To order Munich Airport for £11.99 with free UK p&p call Guardian book service on 0330 333 6846 or go to guardianbookshop.co.uk.