In the United States, no gun is fired and no bird falls to the ground without the incident at once being appropriated by both sides as ammunition in a culture war. Democratic politics having been finally wrestled to the ground by big business and big finance, the most bitter field of controversy has shifted from how we're governed to how we behave. The smallest incident, it seems, is proof of an existing argument, one way or another. Up till now in the United Kingdom we've been spared a great deal of this mindless back and forth, but the recent revelation of Jimmy Savile's vile character has brought signs that things are heading the same way. Traders in opinion have had an orgy throwing Savile against the wall to see what sticks.

To entrenched analysts on one side, Savile is represented as the embodiment of deep cultural misogyny. Throughout his life he referred to the women he violated as "it". In the view of the left, he is a Conservative con man who dined yearly at Chequers, a shameless Tartuffe to the royal family, and, disgracefully, a celebrity all too ready to blackmail individual members of the Prison Officers' Association to prevent strikes, after his appointment to the Broadmoor task force was approved by Edwina Currie at the Department of Health. "Attaboy!" wrote Currie in her diary, when Savile told her of his plans for the hospital. "Jimmy is truly a great Briton," added Mrs Thatcher, "a stunning example of opportunity Britain, a dynamic example of enterprise Britain, and an inspiring example of responsible Britain." But to kneejerk polemicists on the right, looking for satisfying corroboration of what they already believe, Savile is, to the contrary, shocking proof of the moral downside of the new freedoms of the 1960s, and an indictment of two handy ideological targets, which may therefore, they hope, be tarnished by association: the National Health Service and the BBC. A hapless medical expert who argued in this newspaper that Savile wasn't evil but more likely a victim of bad parenting was immediately torn to pieces in the correspondence columns by the readers.

The best hope for the publication of a substantial book by the journalist who spent most time with Savile and who interviewed him frequently is that stale controversy may at last be refreshed by the application of a few facts. The portrait painted by Dan Davies might as well be that of a murderer as of a rapist. Born in Leeds in 1926 as the last of seven children to a ferocious mother, Agnes, who was to remain the sole love of his life, Savile was a solitary child who played alone. When sent down the mines as a Bevin boy, he realised that by turning up in a suit, working naked, then washing his hands and feet while at the bottom of the pit, he might come back up to leave the mine after a day's work as immaculate as when he arrived. In his own words "The effect was electric … I didn't do it for any reason, I just realised that going back clean would freak people out, and it did. Underneath the clothes I was black as night. But I realised that being a bit odd meant that there could be a payday."

Having stumbled on what Davies calls the power of oddness, Savile was then exhilarated to discover he could compound his power by becoming a disc jockey. At once he relished the feeling of control, allowing people to dance, fast or slow, only as and when he wanted. He loved what he took to calling "the effect": "That's the thing that triggered me off and sustained me for the rest of my days." By the time he became a manager of Mecca dance halls, first in Ilford, then in Manchester, he was deploying a distinctive mix of gangster boasting, financial greed and abuse of both sexes, often under age, while moving smoothly on to a career in television. This time, the "effect" of his TV debut was immediate. When he returned to the dance hall to find people queuing round the block, he took special pleasure in them falling a step back, impressed, as he walked by. "I thought: 'Fucking hell, this is like having the keys to the Bank of England.'"

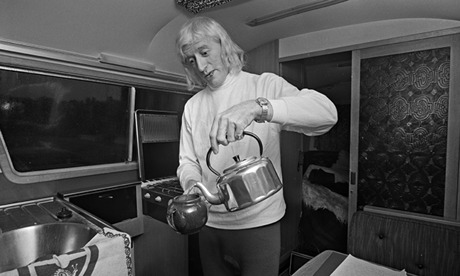

Throughout the book it is presented as paradox that Savile, the best-known presenter of TV programmes for young people, hated children. But it would be truer to say he hated people. He had no interest in relationships. "I just don't have those feelings with another human being." Self-evidently he hated women, on whom he simply sought to leave a violent and degrading stain, throwing them out of his Rolls-Royce if, during sex, they threatened to gag on its leatherwork. But, friendless and intensively competitive, he wasn't crazy about men either, unless, like Prince Charles – who Princess Diana said regarded Savile as his mentor – they were in a position to make him yet more powerful. As an intelligent man with an IQ said to be 150, Savile realised that if he could get tame policemen on his side by a mixture of bribery and flattery, he would be able to bluff his way in the face of the accusations that would inevitably begin to mount up. "Why tell the truth," he asked, "when you can get away with a lie?" Briefly called in as a suspect in the case of the Yorkshire Ripper, he had, he said, "more front than Blackpool". His technique for dealing with his victims was always to keep on the move. "If anyone makes demands, they don't make them twice, pal, because they get the sack after the first time." In a life roiling with sinister self-knowledge, nothing is more chilling than his declaration: "There is no end of uses to a motor caravan."

In normal circumstances, anyone who declared that the five days they spent alone with their mother's coffin were the happiest of their life – "Once upon a time I had to share her with other people … But when she was dead, she was all mine" – would be subject to some public scrutiny. So would somebody whose first reaction after quadruple bypass surgery was to grope the attendant nurse's breast. But by then Savile had pulled off the brilliant trick of seeming to make his surface weirdness part of what he called his "charismatic package". "Nobody can be frightened of me. It would be beneath anyone's dignity to be frightened of someone dressed like this." The popular press, always loudly boastful of its fearlessness, was effectively scared off. In the words of one Metropolitan police commander, "he groomed a nation". In his own words: "I am a man what knows everything but says nothing." As he moved to consolidate his position and to work for the knighthood that he believed would make him untouchable, he took to raising vast sums of money for charity, most especially for a spinal injuries unit at Stoke Mandeville. His first question on arriving in any town was to ask where the hospital was. This was not just because a hospital offered sexual pickings and a captive audience for his ceaseless self-glorying monologues. Nor was it wholly because he needed the immunity that came from apparent respectability. Most important of all, he believed that the day would come when he would have to offer his good works as some mitigation against a final reckoning.

Apart from his mother, God is the only other supporting character in Savile's story, the only one who is granted more than a walk-on part. "When I'm holding somebody that has just died I'm filled with a tremendous love and envy. They've left behind their problems, they've made the journey. If somebody were to tell me tonight I wouldn't wake up in the morning, it would fill me with tremendous joy. Sometimes I can't wait." Savile does not belong among the amoral heroes of Patricia Highsmith, disposing of people without remorse in a meaningless universe. Rather, he inhabits the driven world of Graham Greene, where the protagonist is in a lurid and sweaty argument with his maker, trying to pile up credit points to balance the final ledger against what he knows full well to be his sins. If the definition of a psychopath is someone who does not understand his own depravity, then Savile is, to the consternation of medical apologists, the very opposite. He always carried the rosary the pope had given him. On his deathbed, he was found with his fingers crossed.

In his book God'll Fix It, which collects his thoughts on matters religious, Savile offers a weaselly line of defence, claiming that everyone's true identity is hopelessly in hock to the desires they are given and over which they can hope to have no control. The machine of the body that God has lent you may cause you to err, but nothing is finally your fault. "It could be that the person arriving at the judgment seat had been given a body prone to excesses because the glands dictated that he should be more than was really normal." He defends Broadmoor's inhabitants as "more unlucky than bad", and argues that "There's no point asking about that dark night … when something terrible happened because it wasn't them doing it. It was someone else using their body." When asked if he has been following the Myra Hindley story he replies enigmatically: "I am the Myra Hindley story." Like many Roman Catholics, he is concerned to make a good death – it's one of the most important things in his life – but at no point is he ever known to give a moment's thought to the tormented deaths waiting for those whose lives he has ruined. Even in guilt, the drama is always about him. By the time he has been encouraged by his admirers to lead a peace march across Northern Ireland and to claim that he has been mooted as a potential intermediary between Begin and Sadat to reconcile warring parties in the Middle East, then what Davies calls Savile's messiah complex has taken up every inch of space in his head. A stretcher-bearer at Leeds general hospital commented on the award of his OBE: "They often say he's a bit of a twit. Us, we say he's a bit of a bloody saint."

There is nobody in the world who wants to read a bad book about Jimmy Savile, and there may well, for understandable reasons, be a limit to the number of people who want to read an outstanding one. Davies scarcely puts a foot wrong, interweaving Savile's story with a devastatingly detailed account of how the BBC's dysfunctional news department managed in 2011 so completely both to suppress the scoop of Saville's offences and then, unbelievably, to further mishandle the admission of that suppression. The only errors of tone occur when the author obtrudes himself in the manner of self-conscious literary reportage, gussying the narrative up with needless speculation about his own personal motives for his longstanding obsession with his subject. We don't care. If the book is considerably less depressing than you might anticipate, it's because the act of biography itself here seems noble. Four hundred and fifty people have so far made allegations of sexual abuse against Savile. Across 28 police areas in England and Wales, he is known to have committed 214 criminal offences in 50 years. There are 31 allegations of rape, half of them against minors, and Dame Janet Smith's independent review at the BBC is believed to be about to claim that up to 1,000 young people may have been abused by Savile in the corporation's dressing rooms. All religions rely on the notion of redemption, but the only redeeming feature of Savile's life is that he has posthumously lucked into such a clear‑eyed and morally conscientious biographer. Prince Charles once wrote "Nobody will ever know what you have done for this country, Jimmy." They do now.

• To order In Plain Sight for £14.99 with free UK p&p call Guardian book service on 0330 333 6846 or go to guardianbookshop.co.uk.