If you subscribe to the New Yorker, you'll already know of the genius of Roz Chast, a cartoonist who can make pretty much anything – boredom, chronic anxiety, existential dread – seem hilariously funny. And yet, with Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? she has surpassed herself. A memoir of decrepitude – specifically, the decrepitude of her batty parents – her brilliant new book is honest, plangent and thoroughly ghoulish. But it's also hysterical: I mean wake-up-your-sleeping-husband hysterical. Every time I opened it, I hooted like an owl. Even now, a full month after I first read it, I still can't stop myself from quoting its best lines over the breakfast table in what I imagine to be a comedy Brooklyn accent.

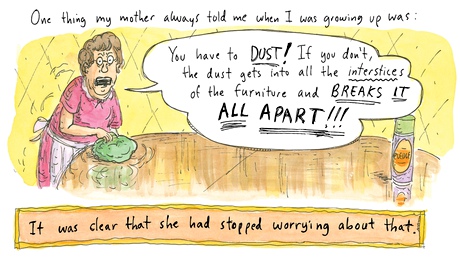

Ah yes, Brooklyn. The Chasts live in what we might call la Brooklyn profonde, far away from the hipsters of Park Slope, in the same grimy apartment in which they brought up their only child. When we take up the story in 2001, George and Elizabeth, who were born 10 days apart in 1912, have been married for 63 years. Theirs is a strange, lonely, inward-looking relationship. George, though gentle and loving, is a phobic who is terrified of everyone and everything – even changing a light bulb is beyond him – while Elizabeth is a harridan who takes great pleasure in giving those who cross her a "blast from Chast". They have no friends and few relatives. Roz, who lives in Connecticut, dreads visiting, for their home is a hoarder's paradise. (My favourite detail on this score is the "cheese-tainer" she finds in their filthy fridge, an invention of Elizabeth's from the 1960s which consists of some bits of ancient Tupperware held together with brown tape and is designed to hold… cheese.) However, she can no longer ignore the situation. Her parents, increasingly ill and frail, are simply not coping.

What follows is an account of the final years: the care homes, the hospitals, the funeral parlours. Naturally, this is sad and grim. Chast, though, isn't one for mawkishness. She never loses sight of her parents' eccentric, calcified personalities. ("Your father had an egg in his pocket all day yesterday," says Elizabeth, during one of Chast's visits. "Thank God, it turned out to be hard boiled.") Nor is she kind to herself, detailing with some vigour and not a little venom her ongoing rows with her parents (once a daughter, always a daughter). As their bills mount, she worries about her inheritance. Clearing out their apartment, she photographs its toppling, sticky piles, and meanly reproduces these images for our disgusted inspection. And when it all gets too much, she will offer up one of her trademark skits, from the Wheel of Doom, a game based on the cautionary tales of her childhood, to an ad for Do Not Resuscitate merchandise. (Don't stop at a plastic wristband! Why not invest in a DNR baseball cap?) Truly, this is the best, most singular work Chast has ever done, and you should rush out and buy it, for yourself and for everyone you know. We're all headed here in the end.