Franny and Zooey is just 157 pages long. I write that not to advocate it as a quick read or even to suggest that it might be cheap (although both might be handy for the beach). I point it out because its length is wildly deceptive. For within what Salinger himself described as a "pretty skimpy-looking book", he manages to steamroll a sizeable chunk of the human condition.

Published in the New Yorker in 1955 and 1957 as a short story and a novella, Franny and Zooey first appeared together in 1961. The curtain rises on Franny as the eponymous fresh-faced American college girl, Frances Glass, arrives by train to meet her boyfriend, Lane, ahead of a big university football match. But over lunch, Franny's skittish, intellectual gaiety begins to crack, revealing a bitter abhorrence of phony experts, narcissistic ambition and above all, ego.

Reeling from the vitriol, Lane notices a small book in Franny's bag and, in quizzing her, provokes an outpouring of enthusiasm for this virtuous tale of pilgrimage and prayer. It seems that the book has triggered her torment. Indeed, as the scene marches towards its frantic climax Franny collapses under the mental strain.

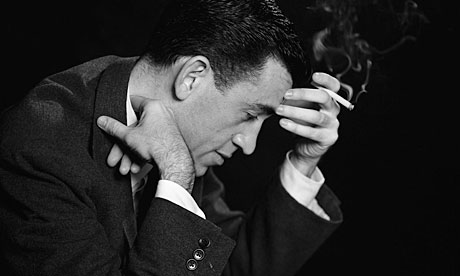

Zooey, the second act of the drama, is played out in the family apartment in New York, where Franny has taken to the couch in distress. The titular character is her brother, an agile young actor who chain-smokes cigars, punctuates every sentence with "goddam" and is constantly tormented by his other five siblings who are, variously, dead, teaching, running a household or living as a Carthusian monk.

As Zooey battles with his mother's concerns over her ailing daughter and beards Franny about the true reason for her trauma, it's impossible not to get drawn into the verbal crossfire. I am in that living room – constantly on the verge of telling them both where to get off. Not that it would be any use. All seven of the Glass children are sharp-witted intellectuals whose perspicacity was honed by regular appearances on a popular radio show "It's a Wise Child"; they're obsessed with learning and seem to have swallowed the entire philosophical canon of both east and west.

I have read this family drama on countless occasions, yet its intense, feverish quality hooks me every time. Franny's bilious outpourings may be wildly out of proportion, but they are refreshingly premised on an intellectual wrangle rather than a romantic tangle, flimsy political intrigue or financial conundrum. And while the relentlessness of Zooey's row with Franny is undoubtedly exhausting, Salinger has created one of the few realistic family bust-ups in modern literature. But for me it's Zooey's exasperated, endearing, intolerant relationship with his mother that makes this book a true gem. Absurdly bath-bound, Zooey quarrelling with his world-weary mother through a shower curtain is an antidote to all the trite, saccharine and consciously obnoxious relationships that abound in more crowd-pleasing literature.

Perhaps, then, it is surprising that Franny and Zooey became an instant hit. But while the public took to the Glass progeny, these perplexing figures weren't universally beloved – and Salinger knew it. The Wise Child's readers, he noted, were split between "those who held that the Glasses were a bunch of insufferably 'superior' little bastards that should have been drowned or gassed at birth, and those who held that they were bona fide underage wits and savants, of an uncommon, if unenviable, order". That Salinger found them irresistible irked the critics. "Salinger loves the Glasses more than God loves them," wrote John Updike in the New York Times. And indeed, he returned to the Glass family again and again in a clutch of stories.

The Catcher in the Rye may be Salinger's most famous book, but for me, Franny and Zooey is his masterpiece. Frenetic, exhausting and uncompromising, this "skimpy-looking book" might piss you off rather than perk you up. But one thing's for sure – it won't leave you cold.