There is a gap in the popular image of the 19th century somewhere around the 1820s and 30s. Between the Regency and Queen Victoria, history seems to skip a beat and the world of Pride and Prejudice – decorous, provincial and populated by men and women of the middle and upper classes – suddenly gives way to the swarming streets of Dickens's London and flickering gaslight throwing up the monstrous shadows of Uriah Heep and Fagin.

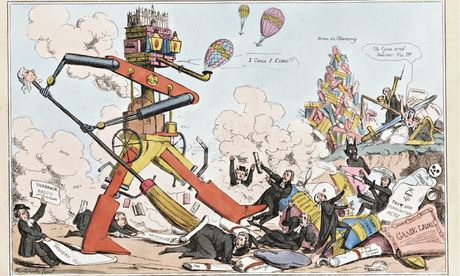

Gaslight was indeed a product of the intervening years, as was much of what we think of as modern science, the electoral system, railways and some of the worst civil unrest in English history. If the last Georgian decades have failed to leave any single coherent impression it is not because too little happened, but because there was too much to make for easy characterisation. What may now look like "the dawn of the Victorian age", as James Secord's subtitle has it, was to contemporaries an era all of its own in which The March of Intellect, portrayed in a cartoon of 1828 as a giant steam-driven robot sweeping away the established order, was changing everything for better, or for worse.

The new steam-powered printing presses brought cheap reading matter to ever larger audiences and among the books available to buy or borrow were the founding texts of subjects from psychology to physics. Secord wades into the maelstrom of ideas to consider seven works that were influential and controversial. As he did in Victorian Sensation, his study of Robert Chambers's Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, Secord starts from the premise that a book's importance is to be gauged as much by who read it as by who wrote it. Vestiges, which set out the argument for evolution, was in its day a more popular book than Darwin's Origin of Species, which appeared 15 years later, and far more shocking. Its later obscurity meant that its significance, not least its effect on Darwin himself, was forgotten. The works Secord discusses here have become similarly dim in historical hindsight. Even if the titles are familiar, the books themselves are seldom read. Secord not only reads them, he pays close attention to the way they were presented, the price, the paper quality, the format and hence the readership. The result is a vivid insight into this turbulent age of "signs and wonders".

If one question preoccupied the thinking classes of the 1830s more than another it was time. Newton had long since opened up space, but time remained trapped in biblical chronology, which reckoned the Earth to be about 6,000 years old. It was increasingly clear that this was not enough to account even for human history, but evidence for an alternative theory was slow in coming. It emerged from one of the newer sciences when the first part of Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology was published in 1831. Lyell's theories about the formation of the earth broke the time barrier and his book, Darwin found, "altered the tone of one's mind". Many minds were altered in due course, but as Secord makes clear the process was gradual and the alterations various. For some people it meant the end of God. The atheist Charles Southwell sent for Lyell's Principles when he was in prison for blasphemy. Yet many contemporaries read it as a way of reconciling the material evidence of the fossil record with the slow unfolding of a divine plan.

This is another effect of hindsight that Secord sets out to correct, the tendency to tell the history of science in terms of inexorable progress and sudden transformative discoveries. One insight did not, as he makes clear, necessarily lead to the next. Lyell did not believe in evolution. The theories of "transmutation" between species, which were already current, appalled him. His notebooks record his horror at the prospect of mankind as nothing but an "improved" ape, of the sort that could be seen at the newly opened London Zoo. The March of Intellect was in reality a series of charges into the unknown, many of which led up blind alleys. Among the new disciplines phrenology attracted as much popular interest as geology, and Secord gives it its historic due as a theory, persuasive in its day and the starting point for later debates about the nature of mind and the brain.

He also records healthy levels of scepticism and humour amid the intellectual fervour. Phrenology was parodied as "Toe-tology", the science of denoting character from the shape of the feet, while Georgian science fiction began a long tradition of being wrong about the future with predictions involving self-propelling houses, man-powered flight and machines to do everything. Cartoons depicted people too busy reading to see where they were going and falling into cellars or colliding with fellow readers, and mental indigestion was a common problem. Having just finished Mary Somerville's On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, the novelist Maria Edgworth reported feeling like a boa constrictor "after a full meal".

While Lyell sought to camouflage the more disturbing implications of his theories by publishing his Principles with John Murray, Walter Scott's publisher, making the book reassuringly respectable and expensive, Somerville wanted to reach as wide a public as possible. Her work appeared in sixpenny instalments. It marked a significant stage in the transformation of natural philosophy into physics and its intended audience was enthusiastic: "Read it! Read it!" shouted Mechanics Magazine. Somerville was unusual as a successful female author in the sciences, but she was not unique and among readers women constituted an important part of the market. Along with men of the lower middle and artisan classes who were similarly excluded from universities and learned societies, they seized the opportunity to join debates into which they could enter as informed participants.

With so many new subjects emerging, definitions were needed. Coleridge and the philosopher William Whewell worked to tease out the old "natural philosophy" from the new kind of "science" and books that promulgated the evolving ideas were themselves a similarly provisional, hybrid genre. Their multifaceted potential was exploited by publishers. Longman's issued John Herschel's Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy in 1830 with three different title pages, allowing the buyer to consider the book as a free-standing work or as part of one of two series, either the existing Cabinet Cyclopaedia of general knowledge or a new more specialist series on natural philosophy of which it was to be the first volume. While Discourses is now usually considered in relation to a tradition of philosophical reflections on induction and metaphysics, most of its tens of thousands of original readers would, Secord suggests, have understood it quite differently, as a guide to conduct. The principles of empirical inquiry, truthfulness, consistency and morality, were also those of the gentleman and the newly self-educating classes aspired to both knowledge and gentility. The self-help manual was, it seems, another product of the 1830s. Secord covers so much ground it would be churlish to complain that he does not make more of the connections with parallel developments transforming the study of history. It only reinforces his argument for the peculiar spirit of the age to point out that the late Georgians' obsession with time made them as interested in the past as the future, and that these years gave birth not only to physics and geology but also to the rediscovery of the Middle Ages and the adoption of gothic architecture as a national style. Visions of Science is a wonderfully lucid account of a complex and often misunderstood era that poses important questions about the way we understand both science and history.

• Rosemary Hill's books include God's Architect, about Pugin.