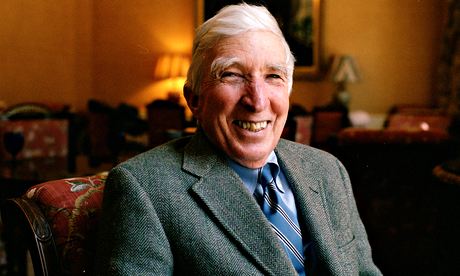

Only truth is useful, John Updike once wrote; only truth, however harsh, is holy. Fiction may have been his preferred mode but autobiography was the subtext – the truth, slightly arranged: "Parents, wives, children," he said in his memoir, Self-Consciousness, "the nearer and dearer they are, the more mercilessly they are served up." A late poem put it more self-accusingly: "I drank up women's tears and spat them out / As 10-point Janson, Roman and ital." Yet the people whose lives he used rarely protested they'd been demeaned or libelled. His tone, in the main, was celebratory. As Adam Begley puts it in this fine biography, Updike "was enthralled by the detail of his own experience", and the magic rubbed off on those around him.

It helped that his early years, as a cherished only child in the small Pennsylvanian town of Shillington, were so idyllic. While his gloomy, stoic father taught high-school maths, his mother stayed at home to nurture him, setting a precedent by clacking away on her typewriter. Though 10 of her stories were later published in the New Yorker, he spoke of her as a would-be writer from whose failure he took off ("My mother knew non-publication's shame / … Mine was to be the magic gift instead"). She predicted great things for him, but her efforts on his behalf weren't always appreciated. When he was 13 she moved the family to the small, isolated farmhouse where she'd grown up, quarantining him from his girlfriend and other lowering urban distractions. It was only 11 miles away but felt like an expulsion from Eden. In his fiction, Shillington became Olinger, a town bathed in nostalgic splendour, the home he'd lost.

His first ambition was to be a cartoonist, ideally the next Walt Disney. Even after Harvard, where he'd done artwork for the prestigious college magazine Lampoon, he persevered with his drawing, spending a year in Oxford at Ruskin School of Art. His English sojourn wasn't entirely wasted; from his art teachers and the fiction of Henry Green, he learned how to "paint things the way they are". By then the New Yorker had already accepted several of his stories. And once he returned to the US he joined the staff. Thanks to the magazine's lucrative sponsorship, he never had to worry about money again.

He was already a father at this point, his wife, Mary, whom he'd married at 21, gave birth to their first child in Britain. Older, posher, more bohemian and sophisticated than Updike, Mary gave him "social aplomb" and helped him conquer his stutter, psoriasis and country-boy gawkiness. But in New York it was she who felt out of place, a stay-at-home mother while he roamed the city in his capacity as a Talk of the Town reporter. After two years, and the birth of their second child, he too was dissatisfied with New York's "ghastly plenitude" and "urban muchness". Still only 25, he fled the bright lights for the small pond of Ipswich, near Boston. He would remain a New Yorker fixture till he died, but he never lived in New York again.

In Ipswich he settled into the daily routine that he'd keep up for the next 50 years: a minimum of three pages written in the morning, then reading, correspondence, recreation and practical tasks (not least carpentry) about the house. Over time, he became dangerously fluent, joking that he wrote more quickly than he read. He never had an agent; meticulously attentive to typography, layout and jacket design, he took care of all publishing matters himself. There were early setbacks, but with Rabbit, Run, his second novel and the first in the Harry Angstrom quartet, critics who'd thought of him as a purveyor of slickly amenable short stories acclaimed him as a major talent.

Meanwhile Ipswich was turning out to be not a quiet backwater but a rowdy adult playground. Updike and his wife found themselves part of a crowd of young couples who'd get together for dinner parties, dances and clambakes, for music, poker and golf, and for Sunday sports with their children followed by cocktails. Rediscovering his gabby, giggly, high-school self, Updike became gang-leader and chief prankster. His new friends were the "sisters and brothers I never had", he wrote. As the "post-pill paradise" of the 1960s dawned, some of the women became more. Adultery went with the territory and Mary also took a lover. Physically Updike was no Adonis, but summer sunshine cured his psoriasis and in a "herd of housewife-does" he became, he boasted, "a stag of sorts". It became a matter of pride, one woman told Begley, to sleep with him.

To protect their privacy, Begley declines to name the women with whom Updike had casual affairs and sticks to the only two of real significance. The affair with Joyce Harrington in 1962 narrowly avoided ending Updike's marriage and resulted in him taking off to Italy for several months with Mary and the children (there were now four) in order to placate the litigious fury of Joyce's husband. The second affair, with Martha Bernhard, did end his marriage, but not until 1977, after two years of "furtive semi-bachelorhood" in Boston (the only period Updike ever lived on his own). Torn between his wife and mistress, reluctant to abandon his children but convinced that "the obligation to live … must be defended against the claims even of virtue", he finally divorced Mary and married Martha, remaining with her, in increasingly seclusive affluence, till his death more than 30 years later.

Begley's sense of discretion may disappoint the prurient (those who'd like to know, for example, who exactly it was Updike claimed to have masturbated through her ski pants in the back seat of a moving car while his wife sat in the front) but it's surely well-judged. The world of Ipswich, aka Tarbox, with its "boozy, jaunty muddle of mutually invaded privacies", is recorded in his succès de scandale of the period, Couples. Putting names to faces wouldn't make it any more vivid; it's not as if these lovers were public figures. Updike himself was untypically cautious about publishing some of his stories at this time, asking his New Yorker editor to put them on hold in what he called "the shadow-bank". Some may feel they already know more than enough about his erotic life: versatile though he was in finding worshipful metaphors for the female body, Couples suffers from its libidinous Joycean exuberance: "[he] fingered and licked her willing slipping tips, the pip within the slit, wisps" etc. Mary, to whom the book was dedicated, said it made her feel "smothered in pubic hair".

Updike's strongest, most self-transcending writing came in his Rabbit books, though Begley makes out a good case for Marry Me as well as for his poetry. For Rabbit is Rich, he worked hard to get a handle on car dealerships: to "give the mundane its beautiful due", he needed to know Harry's working environment inside out. Harry isn't as obvious an alter ego as Richard Maple, whose trajectory over numerous stories enables Begley to track his creator. But Updike did have a natural affection for middle America that few of his literary contemporaries shared. Hence his attempts to portray himself as "a pretty average person", despite having been exceptional from childhood onwards.

After Rabbit at Rest in 1992, Updike could have been forgiven for easing down ("you reach an age where every sentence you write bumps into one you wrote 30 years ago"), but the books kept on coming – 10 more novels, as well as collections of stories, essays and poems. There were fallings-out (with Tom Wolfe and Philip Roth), denunciations of his position on US foreign policy (he saw himself as an "undove") and feminist attacks on his objectifying male gaze (a priapic narcissist, some called him, "a penis with a thesaurus"). With no Nobel forthcoming and a younger generation turning against him, he began to portray himself as a has-been well before he reached his 70s. He was gloomy about posterity, too ("who, in that unthinkable future / when I am dead, will read? The printed page / was just a half-millennium's brief wonder"). But feeling miserable, as he occasionally did, never stopped him from writing. And for the most part his sunny disposition endured: the natural state of human adults is a qualified happiness, he thought. The end came quickly and unexpectedly, five years ago – a diagnosis of stage-four metastasic lung cancer, when he thought he had pneumonia. There was still time for him to write some moving poems, fearful of death and nostalgic for his Shillington childhood: "Perhaps we meet our heaven at the start and not / the end of life".

Begley's relationship with his subject goes way back: Updike was a college classmate of his father, and once entertained the infant Begley by juggling three oranges from a fruit bowl. As a biographer he's admiring without being over-protective, and is particularly good on Updike's contradictions – as an erudite populist, Lutheran hedonist, church-going iconoclast and smiling public figure with a knife. Inevitably, the book is tilted towards the first half of Updike's life (which laid the ground work for so much of his fiction) and his first marriage. Whereas Mary and their four children co-operated with Begley, and offer some poignant insights, Martha is conspicuously absent in the Acknowledgments, and – as spoken of by others – sometimes comes over in an unflattering light. If there's an injustice in that, future biographies will have to put it right. Meanwhile this one paints a portrait Updike would have recognised and even, for the most part, approved.