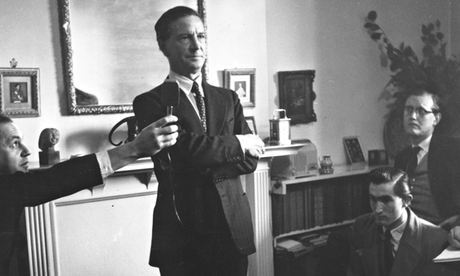

Nicholas Elliott, the MI6 officer who flew to Beirut to extract a confession from Kim Philby or, as some suggest, deliberately let him go, spoke wistfully about the notorious Soviet Spy.

We met at the Travellers, the spies' club in Pall Mall, three decades after Philby, in 1963, boarded a Russian ship bound for the Ukrainian port of Odessa. With misty eyes, Elliott spoke fondly of his former close colleague in the Secret Intelligence Service.

Anthony Cavendish, a former MI6 officer did not know Philby so well. In his book, Inside Intelligence, Cavendish describes Philby as a traitor "whom I counted as a drinking companion". But over several drinks at the Cavalry and Guards Club in Piccadilly, Cavendish, too, shared fond memories of Kim.

"He enriched my world for many years and I owed a lot to him," wrote Tim Milne, another of Philby's friends in MI6. "Certainly my association with him caused many difficulties for me, but I do not feel bitterness towards him, only sadness".

These are just a few of the deeply felt sentiments about a ruthless spy who sent scores of people to their deaths.

A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal, by Ben Macintyre (Bloomsbury), Kim Philby: The Unknown Story of the KGB's Master Spy, by Tim Milne, and Macintyre's BBC2 series, Kim Philby: His Most Intimate Betrayal, are the latest revealing accounts of the extraordinary complacent and self-satisfied culture in the upper reaches of Britain's secret intelligence establishment.

They are unlikely to be the last. MI6 and Foreign Office files on Philby and the rest of the Cambridge spy ring remain in closed archives. They are contained in 19 boxes of files, including some marked "Investigations into the disappearance of [Guy] Burgess and [Donald] Maclean, including assessments of their personalities".

Whitehall guardians of the archives are reluctant to release them, because they would shed more light on a deeply uncomfortable truth: Philby was protected, and Britain's national security undermined, by little more than snobbery.

Elliott could not believe, until the evidence was compelling, that Philby, a member of the Athenaeum (adjoining the Travellers) was a Soviet spy. Sir Stewart Menzies, head of MI6 at the time and staunch defender of Philby when confronted by MI5's suspicions, was a member of White's club, and as Macintyre observes, "rode to hounds, mixed with royalty, never missed a day at Ascot, [and] drank a great deal ..."

Philby's father, St John Philby, was captain of Westminster school, which Kim attended and where he first met Tim Milne, who later joined him in MI6. (St John, Milne notes, was an "Arabist of unorthodox views". An adviser to Ibn Saud, the first king of Saudi Arabia, he converted to Islam). After junior school at Durnford, where he became friends with fellow pupil Ian Fleming, Elliott was educated at Eton, where his father was headmaster.

So Elliott and Philby effortlessly joined an inner closed circle of a kind unique to Britain. Macintyre quotes from a lecture CS Lewis gave in 1944. "Of all the passions," said Lewis, "the passion for the Inner Ring is most skilful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things."

Elliott went from elite to elite (Cambridge to MI6); Philby went further and became a spy for the NKVD (forerunner of the KGB). So, too, did other members of the Cambridge Spy Ring – Maclean (Gresham's School), Burgess (Eton), Anthony Blunt (Marlborough College), who were also all members of that other elite society, the Cambridge Apostles.

Maclean and Burgess fled to Moscow in 1951 after a tip-off from Philby, the "Third Man". Philby brazened it out with the help of his charm, what his friend Milne called his "personal magnetism", his clubbiness and, above all, his background. That was until a Russian defector, Antoliy Golitsyn, produced intelligence that pointed directly at the Ring of Five, including Philby.

MI6 convinced MI5 that Elliott, Philby's close colleague, was a better man than MI5's hard-nosed interrogator Arthur Martin to question him and extract a confession in return for immunity from prosecution. The last thing the security and intelligence establishment wanted was a public spy scandal so soon after the exposure, trial, and conviction of George Blake. Blake had confessed to spying for the Russians during a clever MI5 interrogation after being fingered by a Polish defector in 1961. (Roger Hermiston's The Greatest Traitor, The Secret Lives of Agent George Blake has just appeared in paperback.)

Blake was sentenced to 42 years in jail, at that time the longest sentence ever handed down by a British court. "The Lord Chief Justice has passed a savage sentence – 42 years in prison! Naturally we can say nothing," the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, noted in his diary. MI6 was almost as stunned as Macmillan, for such a sentence would hardly encourage any future Soviet spy to confess.

Blake was a foreigner (his father was an Egyptian Jew, naturalised British, and his mother was Dutch), a bit of a loner, not a gentleman and certainly not clubbable; he had not been offered a deal, unlike Philby and the two remaining members of the Cambridge Spy Ring: Blunt and John Cairncross.

Blunt confessed in 1964 after he was named by Michael Straight, an American and former member of the Apostles whom he had recruited. He was protected because he was surveyor of the Queen's pictures – the Queen was herself told but kept the secret. In 1979, the new prime minister, Margaret Thatcher brushed aside the advice of the Whitehall establishment and publicly revealed Blunt's past as a spy after he was thinly disguised in Andrew Boyle's The Climate of Treason.

Cairncross, too, was offered immunity from prosecution and moved to Rome where he became the correspondent for the Observer newspaper and Economist magazine. After Philby was forced to resign from MI6 because of his past close association with Burgess, Elliott managed to persuade David Astor, editor of the Observer (and educated at Eton), to give him a job as correspondent in Beirut, where he also reported for the Economist.

But the parallels end there. A brilliant scholar – he came first in exams for both the Home Civil Service and Diplomatic Service – Cairncross was the son of a manager of an ironmonger's shop near Lanark in Scotland. In his book, The Enigma Spy, published posthumously, he distanced himself from the other members of the Cambridge Ring whom he regarded as privileged and effete members of the upper classes. But that class in the end had helped to save him from prosecution just as it did the other members of the Ring.