It looks as though we're about to see a resurgence of interest in American crime writer Patricia Highsmith and frankly, it's about time. This month brings the re-release of her book The Two Faces of January, ahead of a movie adaptation starring Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen, which comes out in May. In March, Virago released Highsmith's novels as ebooks for the first time and in September they'll publish the three books she wrote in England (The Glass Cell, A Suspension of Mercy and Those Who Walk Away) in paperback with new introductions by Joan Schenkar, author of the biography The Talented Miss Highsmith. Perhaps most enticing of all, Highsmith's 1950s lesbian romance Carol is currently being made into a film by Todd "Far From Heaven" Haynes, starring Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. Yet even a movie with this kind of cachet might not persuade people to revisit the source material.

When Anthony Minghella's adaptation of The Talented Mr Ripley came out back in 1999, it sparked a mini Highsmith revival, with the mandatory movie tie-in re-release of the novel. But audiences seemed more interested in Matt Damon's star turn and Jude Law's cheekbones than Highsmith's writing, which is understandable, but disappointing. Because while it's a respectable film, it fails to replicate the tension and creeping menace of the novel ("He liked the fact that Venice had no cars. It made the city human. The streets were like veins, he thought, and the people were the blood, circulating everywhere"), or the breathless excitement of reading the story of Tom Ripley, a small-time conman who becomes a rich, successful sociopath. ("Mr Greenleaf was such a decent fellow himself, he took it for granted that everybody else in the world was decent, too. Tom had almost forgotten such people existed.")

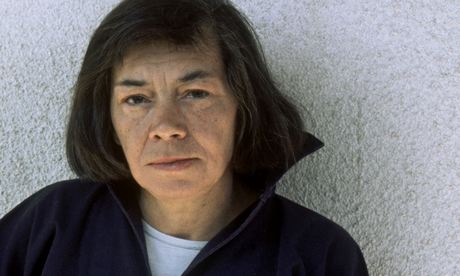

Of course, Patricia Highsmith is hardly unknown. She published eight short-story collections and 22 novels, including the five-book Ripley series and her first book, Strangers on a Train, which Alfred Hitchcock adapted for the big screen (although he wimped out when it came to the ending). She's been the subject of several acclaimed biographies, including Andrew Wilson's Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith, and is often named in lists of the best crime novelists of all time. But she's still something of a niche author, perhaps because her stories are so dark and morally ambiguous, filled with criminals who not only get away with their horrific deeds, but often don't appear to be tortured by them.

Although she's usually shelved in crime and her books slip down as easily as an airport thriller, they have a literary quality that betrays her influences, which included Dostoyevsky, Camus, and Henry James. Her novels have strong plots but also explore the psychology of her characters, who tend to be lonely, sexually confused outsiders (there's a homoerotic undercurrent in much of her work).

Highsmith herself led an isolated life, with few friends or lasting relationships. She was gay, but struggled with the prejudice of the time and her own internalised homophobia, writing in her notebooks that she didn't feel she could reveal her true self to others. According to Andrew Wilson, she was an alcoholic, and her former publisher Otto Penzler called her a "mean, hard, cruel, unlovable, unloving person." She seemed to prefer the company of animals and snails to people, and apparently once took 100 snails in her handbag to a party in order to have someone to talk to.

Less entertainingly, she was passionately antisemitic, writing to newspaper and government bodies under a variety of aliases to complain about Jewish influence and the state of Israel. But while she may not have been pleasant to be around, she channelled her perversity and misanthropy into a singular writing voice: creepy, amoral, but with the kind of close observation that makes her warped characters strangely sympathetic, to the extent that you can't help rooting for them.

Those characters are mostly male – women in her books tend to be background characters, or bland antagonists to the men. Carol is an exception: one of the first mainstream novels to feature a lesbian relationship with a relatively happy ending, it sold nearly a million copies when it was first published in 1952 as The Price of Salt. It wasn't sexually explicit, but the passionate love she depicted ("Then Carol slipped her arm under her neck, and all the length of their bodies touched, fitting as if something had prearranged it. Happiness was like a green vine spreading through her, stretching fine tendrils, bearing flowers through her flesh") was considered so shocking that it was released under the pseudonym Claire Morgan.

It's a landmark book, and worth adding to your to-be-read pile, but I'd particularly recommend picking up Highsmith's more murderous novels, starting with The Talented Mr Ripley.