At the end of a three-day rainstorm, a toothless and sick old man with enormous wings is discovered barely alive on the beach. Nobody understands what the old man is saying. Some say he is a castaway, some say he is an angel – though the priest denies it because he doesn't understand Latin. Locals lock him in a chicken coop and make a fortune by charging visitors to poke fun at him. He becomes a part of some grizzly menagerie with a young woman who has been turned into a tarantula. After a while people lose interest in the man with the fetid wings, and he is left alone. One day he gets up and flies away.

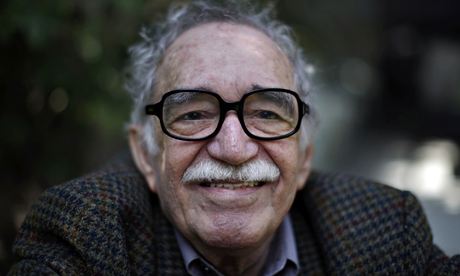

The great Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez didn't invent the genre of magic realism – that style of writing where the supernatural is described as something quite ordinary and where the ordinary is described as something quite supernatural – but, in short stories such as the Kafka-esque A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings and his magisterial One Hundred Years of Solitude, he gave the genre its most formidable works of fiction.

For some, the term magic realism is a broad and baggy one. Initially borrowed from the visual arts, it is often used variously to describe any form of literature that blends the marvellous with the mundane. But more careful observers argue that it is a specific form of post-colonial literature, native to Latin America and the Caribbean. And post-colonial because it employs the magical as a form of imaginative resistance to the harsh and totalising logic of imperial rationality. It seeks the freedom to think outside the box of established wisdom: that is, by rubbing away the line between the real and the fantastic, it frees the imagination from the constraints of how things are. It is revolutionary stuff.

Interestingly, Gabo, as he was affectionately known, always denied his work was "magical". He saw himself as a realist through and through. And Gabo's leftwing political sympathies, his friendship with Fidel Castro and so on, point to a seriousness of purpose that is not usually associated with the literature of fantasy.

All of which is not a bad lens through which to understand the story that animates Christians this Easter weekend. It looks magical – the return of a dead man to life – but it is not treated that way by those who follow the story. And it is post-colonial, even perhaps the foundational literature of post-colonialism – for if the cross is anything, it is the repressive power of colonial authority. The risen Christ being the supreme act of defiance against the power of Roman imperial rule. Nothing can contain the imagination. We can all be free. There is hope. It begins with an act of the defiant imagination, something that cannot be constrained by the logic of grim political inevitability. But it is also deadly realistic. Rest in peace, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. You were a genius.