If Hitler were alive today, would he become a standup comic? Incredible though that may sound to anyone who lived through the second world war, that is the scenario sketched out in Look Who's Back, a satirical novel by Timur Vermes, which topped the bestseller lists in Germany after its publication in 2012 and is now about to be published in English.

In the opening pages, Hitler wakes up on a building site in Berlin in 2011. His memory of how he got there is hazy: "I think Eva and I chatted for a while, and I showed her my old pistol, but when I awoke I was unable to recall any further detail."

The owner of a nearby kiosk recognises him – after all, 66 years after his death the man's face is still ubiquitous – and, assuming that Hitler is an extra from a new second world war film who is remaining resolutely in character ("Bruno Ganz was superb, but he's not a patch on you"), the kiosk owner hooks him up with a local comedy promoter.

Hitler's first gig, the warm-up slot for a Turkish-German comic, goes down like a sinking U-boat. His dark rant about Muslims, abortion and plastic surgery has his audience gasping in shock. But gradually the performance gathers clicks on YouTube.

Bestselling tabloid Bild demands an interview with the "loony YouTube Hitler" in which it tries to call his bluff. "Is it true that you admire Adolf Hitler?" asks the journalist. "Only in the mirror in the morning," Adolf replies. Because Hitler does not adapt to the 21st century and instead just continues to be the Hitler who died in 1945, no one can get a grip on him.

All the tabloids can do is express outrage, which means the more respectable broadsheets start to celebrate this unique method actor's "improv" act as a clever deconstruction of modern morals. Soon, the talkshow circuit beckons, then the leap into politics. Which prompts the question: will Hitler soon be back where he left off in 1945?

Partly thanks to a massive marketing campaign involving popular comedian Christoph Maria Herbst, Look Who's Back (Er ist wieder da), with its cover depicting Hitler's block-like side-parted hair and toothbrush moustache, has sold more than 1.4m copies in print and audiobook in Germany. No mean feat, considering the hardback sold – in a knowing historical reference to the year the Nazi party leader came to power – for a hefty €19.33.

Critics, though, have been underwhelmed. Some argued the novel "trivialised" the dictator's crimes by making the reader laugh not at, but also with him. Others felt the satire just didn't bite enough: "A mediocre joke that suddenly got successful," as author and critic Daniel Erk put it.

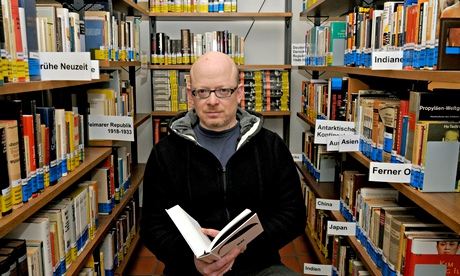

Vermes, a 47-year-old former ghostwriter with a German mother and a Hungarian father, brushes off such complaints: "Books don't have to educate or turn people into better human beings – they can also just ask questions. If mine makes some readers realise that dictators aren't necessarily instantly recognisable as such, then I consider it a success."

Vermes's hunch that a modern Hitler might find a home in comedy is by no means far-fetched. Almost 70 years after the end of the second world war, the web is awash with Hitler humour. Click on YouTube and you will find more than 100 videos made in recent years by satirists snatching clips from Downfall, the 2004 German movie of Hitler's demise, and doctoring them to tell a range of stories about personal travails and world politics. Watch Hitler erupt in frustration over his Xbox or flip out because his friends aren't going to Burning Man. This is the age of the "Hipster Hitler", run by a group of New Yorkers, in which the 21st-century, design-aware "Hipster Hitler" wears T-shirts that say "Heilvetica" and starts another beer-hall putsch because his local doesn't serve the latest craft beer. There is the website catsthatlooklikehitler.com, which has popularised the nickname Kitler for white cats with unfortunate black markings that make them look like the Führer. Hitler's appearances in popular culture and the media, from advertisements to Google requests and the surface of toast, have become so pervasive that leftwing newspaper Taz until recently ran a dedicated Hitler blog on its website, keeping track of them.

Of course, in the right hands, the Nazis have always been comic. Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator set the benchmark for Hitler humour as far back as 1940 (though Vermes's Hitler thinks it's "cheap and shoddy" compared with the real deal).

For the British, initially egged on in wartime to ridicule the Führer by the Ministry of Information, Hitler humour was never really considered out of bounds. And since the war, the leader of the German fascist movement has made regular appearances in British comedy, his jerking body movements and violent outbursts reenacted eerily in Till Death Do Us Part, I'm All Right Jack and Fawlty Towers. He even ran for the Minehead by-election in Monty Python, circa 1970. As author Jacques Peretti once put it: "Hitler was basically David Brent with clicky heels."

In Germany, there used to be more ambivalence about using the orchestrator of the Holocaust as a comic figure, although a compilation of jokes about the Nazi regime was one of the very first books to be published in postwar Germany. Showing that the nation had laughed about Hitler allowed people to claim that some had rebelled against the Nazis, even if those acts of rebellion had been restricted to a whispered punchline or stifled laughter.

In 1949, the year of the foundation of modern Germany, West Berliners enjoyed a cabaret show by satirist Günter Neumann called I Was Hitler's Moustache, about a Hitler body double who gets carried away with his new-found fame. Der Spiegel gave it an emphatic thumbs up: "Hitler's first step on to a Berlin stage was laughed at loudly and at length." Laughing at Hitler was a way of showing you were on the right side.

After the 1968 student protests ushered in a more critical stance towards not just the Nazi leader but the entire generation who had voted him in, it became harder to do comedy about Hitler without looking suspiciously like an apologist. Not having a German passport helped. George Tabori, the author of the first genuine Hitler satire to appear on a German stage, in 1988, was Hungarian. The play, simply called Mein Kampf, imagined a friendship between the young Hitler and a Jewish novelist, who primes him for a career in politics and designs his new look. "There are some taboos that need to be broken unless we want to choke on them," Tabori later said.

The book that in Germany truly ended the debate over whether it was "OK to laugh about Hitler" was an anarchic grotesque by cartoonist Walter Moers, published in 1998, in which the modern dictator starts an affair with Göring, now specialising in domination on the Reeperbahn, and tries to take over the world with Princess Diana.

Far from breaking any big taboos, Timur Vermes's novel may be a sign that Germany now looks at Hitler the way the rest of the world has already done for years: as a stock comic character. "For decades, we learned to see him not as a human being but as a demon," says Klaus Cäsar Zehrer, a German satirist and historian. "Now that's changing, and he's tilting over into caricature: he used to be the ultimate villain, now he is the ultimate idiot."

Increasingly, Zehrer says, Hitler satire is directed less and less at the Nazi period, and more at the few who still genuinely admire him. The funniest chapter of Look Who's Back has Hitler ridiculing the shambolic goings-on of the National Democratic party, the far-right outfit who many see as bearing the marks of Hitler's National Socialists.

That particular chapter may well have been inspired by extra3, one of the few reliable funny comedy shows on German television, which allows a dubbed Hitler to rant about the ineffectiveness of the modern German far right. "It works because for the neo-Nazis, this guy is still someone they look up to," says programme editor Andreas Lange.

In 2008, Lange said his team considered letting Hitler rant about the Chinese Olympic opening ceremony too, but decided to scrap the segment. "The problem with Hitler as a vehicle for satire is that you very quickly get tied up with comparisons you need to justify. We didn't want to use Hitler as if he was some pub circuit standup – there needed to be comedic precision to his contributions."

At the beginning extra3 used to get regular complaints from viewers, but their number has decreased over the years. "It has become increasingly difficult to provoke audiences with the Nazis. Jokes about animals and the church always get complaints – jokes about Hitler less and less so."

Thomas Pigor, a cabaret performer who does a popular chanson about the Führer's aftershave, maintains that the only way to still get any comic mileage out of the Hitler impressions these days is to explore the gap between cardboard cut-out madman and the private human being. "When I do Hitler, I can't start out with the volume at full tilt – people wouldn't find that funny. I give him a low burr – that's where you get some comic potential, in the tension between monstrosity and banality".

Vermes too says he had "a curtailed idea of who Hitler was" before writing his book. "There is this 'instant Hitler' most people know, who is a bit like instant coffee, very one-dimensional."

In search of a Hitler beyond the caricatures, he decided to read Mein Kampf for the first time. "It's written in the style of someone who doesn't normally write: pompous and snivelling, lots of animal metaphors. If one word would do but Hitler knows three, he will use all three."

But, he argues, the book was so dangerous precisely because it's not full of mad ideas. "Some of it is fairly commonsensical. Take Hitler's thoughts on housing: he says young people need houses, so the state should build more houses. We can't declare that wrong simply because it was Hitler who said it."

Vermes's modern Hitler, too, doesn't only spout repellent ideas that would instantly alienate the reader. On the one hand, he rails against parliamentary democracy, decries press freedom, and rejoices at the fact that 65 years after the end of the war, Germany's Jewish population is still only a fifth of what it was in 1933. But on the other, his complaints about hunting, food scandals and drivers racing through inner-city areas would fit perfectly into any modern party manifesto. "That's why many readers thought my Hitler was too real: he was too normal," Vermes says.

The younger the reader, he says, the more they enjoyed his book. His mother, who was born in 1942, failed to see the funny side. "'But that's what Hitler was like,' she said."

Sometimes it feels like Vermes may have studied the ponderous style of his protagonist's memoir a bit too closely: for a comic novel, the opening chapters of Look Who's Back in particular can be a bit of a slog.

And yet there's no question that the novel has hit upon the key paradox of our modern obsession with Hitler. In spite of his current ubiquity – in the media, in advertising, in film and in comedy – we are perhaps further than ever from understanding what he was like as a real human being, or how he was able to lead the German people to participate in the historic crime of the Holocaust.

Und Äktschn! (And Action!), a critically acclaimed comedy released in German cinemas last month, tells the story of an amateur film-maker trying to make a movie about Adolf Hitler's private life. In an interview with Der Spiegel, its director, veteran Bavarian satirist Gerhard Polt, argued that there must have been a likable side to Hitler – otherwise how could he have penetrated the salons of Munich high society? "The likable guys are the dangerous ones. When a likable person gives you a hug and says something terrible, it's much harder to let go."

Look Who's Back is published by MacLehose press on 3 April. Timur Vermes will be speaking at the Bristol festival of ideas, Foyles Cabot Circus, 1 April, 6.30pm. Tickets via ideasfestival.co.uk