Emma Donoghue's Room was the literary sensation of 2010, selling a million copies and narrowly missing out on the Man Booker. The novel – a fiction sparked from the grisly facts of the Josef Fritzl case – belonged to a recent sub-genre of high-end succès de scandale, alongside Christos Tsiolkas's The Slap, Lionel Shriver's We Need to Talk About Kevin, and Herman Koch's The Dinner.

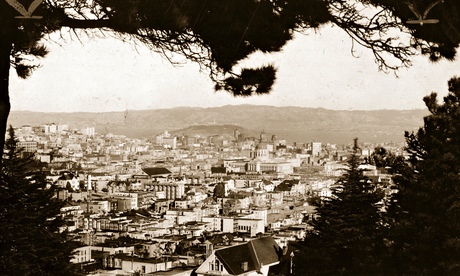

The success of Room rather swamped recognition of Donoghue's previous efforts. She was, in fact, already an accomplished author of historical fiction, with 2000's Slammerkin an atmospheric romp set amid the taverns and brothels of 18th-century England. It should come as no surprise, then, that Frog Music, her eighth novel and the follow-up to Room, is not some grisly modern morality tale, but takes place on the seedy post-gold rush streets of 1870s San Francisco.

Frog Music's heroine is former circus girl Blanche Beunon, now a "soiled dove" – a stripper and occasional prostitute in the city's Chinatown. We swiftly perceive the contradictions that bind Blanche's character – the good-time girl who misses her institutionalised baby, P'tit; the scheming capitalist whose pursuit of wealth leaves her lonely and careworn. She leaps off the page at us, a memorable creation who, while not as fragilely lovable as Jack in Room, is every bit as vivid and alive.

That the novel is drawn from a true story and laced with the ribald lyrics of contemporary songs gives the project added piquancy.

Frog Music opens with the shotgun murder of Blanche's bosom pal, the cross-dressing Jenny Bonnet. Through well-managed cuts back and forward in time, the tale unfurls into a sophisticated whodunnit, with the finger of blame falling first on Blanche's maquereau (or pimp), Arthur, then on his sinister chum, Ernest. As we're drawn tighter into the plot's paranoid web, our suspicions rove across a wide cast of scintillatingly unpleasant characters, all against the backdrop of a San Francisco sweltering under a record heatwave, ravaged by a smallpox epidemic and heaving with racial tension.

There are more similarities between Frog Music and Room than might be expected, and these affinities carry important lessons about the writing of historical fiction. In an interview when Room was published, Donoghue said that, far from being a lurid exploration of the Fritzl character, the novel was instead about parenthood (Donoghue had recently had her first child): "I was trying to capture that strange, bipolar quality of parenthood. For all that being a parent is normal statistically, it's not normal psychologically. It produces some of the most extreme emotions you'll ever have… I wanted to focus on how a woman could create normal love in a box."

This is why Room worked – it had a firmly beating moral heart; it spoke to something essentially human in the reader. This is also what historical fiction needs to do, to use the events of the past to illuminate present issues – to broker, as Hilary Mantel says, "a compromise between then and now".

Frog Music, despite being distant in time and place from the events of Room, turns around many of the same concerns. It is, as Donoghue described Room in another interview, a "defamiliarisation of ordinary parenthood", using historical fiction to consider some very modern issues. Blanche struggles to raise her child while doing a demanding job. She dithers over childcare for P'tit, trying to find a way of maintaining her lubricious lifestyle while dealing with the responsibilities that come with her success – money, a home, offers of ever more lucrative work.

As the narrative hurtles towards its denouement, Blanche learns some ultimately rather conservative lessons about life, love and parenthood: "Blanche will always like her drink, but she'll try to make big decisions in the sober light of day… She will be fierce in P'tit's defence; ambitious for his happiness, which means her own."

More interestingly, the end of the novel also turns around a moment of unsuspected observation, of hurried assumptions and ingrained bigotry. It reminded me of the fabulous murder scene in Richard Ford's Canada, where the horror is intensified rather than quelled by the distance of the narrator, by the windows between him and the gruesome act.

One dud note in an otherwise impressive work: dialogue attribution. In his masterful how-to guide, On Writing, Stephen King recommends that only "said" be used to identify dialogue, and further states that adverbs should never be used in conjunction with identifiers. It's what I call JK Rowling disease (and before I'm lynched by a baying mob, my son and I are on the fifth Harry Potter and enjoying them greatly). But the number of times Harry "shouted angrily" or "whispered softly" or "laughed happily"… It's bad writing, and it's a tic that Donoghue carries over from her earlier work (indeed, it's worse in Slammerkin). On one page of Frog Music, Jenny "remarks", Arthur "quotes" and "barks", Ernest "hoots" and a fat man "demands". Earlier in the book, Arthur "calls theatrically" and Ernest "quotes lugubriously" in response. It's enough to make you long for a clear, hard "says".

It is a small quibble with an otherwise impressively realised and gripping book. Frog Music treads the same grimy San Francisco streets as Patrick DeWitt's excellent The Sisters Brothers; it has the same eye for period detail and the same white-hot pace. Those looking for a misery memoir will be disappointed – although, of course, Room was never one of those in the first place. Instead, this is another smart and finely wrought consideration of parenthood, further proof of Donoghue's significant skill as an author.