Still searching for the perfect Valentine's Day gift? Holding out for something truly unique? Salvation may just have come courtesy of Nanni Balestrini, experimental poet, onetime left-wing activist and self-declared foe of "the stiff determinism of Gutenbergian mechanical typography". For he has created a novel that is more than one in a million. To be precise, it is one in 109, 027, 350, 432, 000.

Branded "a love story that tests the limits of the novel" by its British publishers Verso, Tristano goes on sale in the UK on Friday, almost half a century after its author published its original version in Italian in 1966. But the 4,000 books that have been ordered by Verso are more than simple translations of that work.

In the realisation of Balestrini's original, long-unfulfilled dream, each book is a slightly different telling of the story - a jumbled, randomised mixture of the original generated by a computer algorithm and intended to transform the unsuspecting reader into what fellow Italian Umberto Eco describes as a 'co-author'.

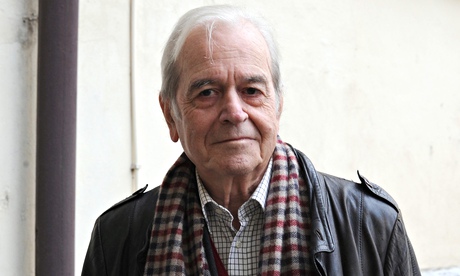

"With mechanical reproduction and typography, everything is made the same. This goes for [the production of] objects, too: these chairs were made in a factory which makes all of them exactly the same," says Balestrini, 78, tapping the seat on which he is perched in his Rome studio.

"And this is unnatural," he says. "Because here we have a tree on which there are leaves which are a bit similar but are all different. The same goes for us: we are a bit similar, we have two arms, two eyes, but we are different people. And I think art should be thus; indeed, it is thus … So for me this mechanical business, which makes all things boring, identical, is very irksome."

Leo Hollis, an editor at independent publishers Verso, said they had decided to bring Tristano to English-language readers because of its position on the cutting edge of technology-transformed story-telling, which Balestrini began experimenting with in the early 1960s.

"I think this is one of the most engaged experiments in the format and in what fiction can be," said Hollis. "Not only is it an extraordinary object but also it can, depending on the edition you get, obviously, be an extraordinary read as well."

When Balestrini realised that digital printing technology had advanced to the stage where his dream of a novel with a huge number of possible variations was now feasible, he and his son came up with a system which would regulate the dismantling and re-ordering of the original Tristano, every time producing a different novel with its own individually-numbered cover.

The first versions were published in Italy in 2007, and subsequently in Germany. Before the English-language editions, 10,000 copies were in circulation. Each has 10 chapters with 20 of a possible 30 paragraphs in different orders, with the paragraphs within the chapters also shuffled. "And from these two rules," says Balestrini, "comes this number of millions, millions, millions of possible copies."

When it was published in 1966, Tristano - named in an ironic homage to the hero of the Tristan and Iseult legend - was already an experimental hodgepodge. Needless to say, its digitally-reordered descendants are not novels- let alone love stories- in any traditional sense. Verso describe the book, in fact, as a "radical assault on the novel"; for Balestrini, it is a literary work- but also "a game" into the spirit of which the reader, if he is to appreciate it, must enter.

At least one appeared to be struggling with this, however; a message posted on Twitter on Saturday read simply: "Reading Balestrini's Tristano. My head hurts."

The writer- whose early work in the 1960s rejected almost all linguistic and narrative tradition- acknowledges that reader frustration "is a risk" and admits he is curious to see how the anglophone world reacts. What he would like is for each person to interact playfully and imaginatively to the words and in so doing perhaps weave a story of their own- "a story which is completely different from that which anyone else could invent."

"I don't know if you've ever gone on the metro and the tram and heard snippets of people's conversation, and you've thought 'but what is this story?'," he says. "And you invent a story; from small fragments of language you create a story out of curiosity."

In an introduction to the book, Umberto Eco, one of the foremost members of Italy's Neoavanguardia movement alongside Balestrini, says he sees three options for potential readers of Tristano: to acquire a single copy and read it "as a unique, unrepeatable and unchangeable text"; to acquire many and "have fun following the unexpected outcomes of the combination", or pick just one they consider to be the best.

Balestrini says the reader should decide for himself how many copies he wants, though suggests comparing two versions for a fruitful analysis. Not that he is perhaps the best person to judge. Since the original of 1966, how many versions of Tristano has he himself read? "None," he says, and chuckles.