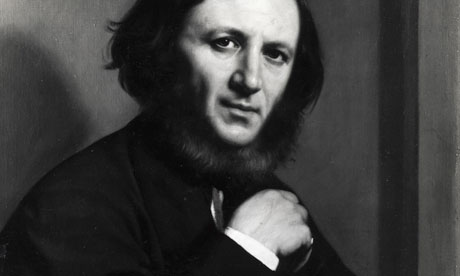

On 7 May we will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Robert Browning. He is one of the towering poets of the 19th century. At the end of his life he was feted and adored. And yet the Browning bicentenary has been attended by none of the extravagance and razzmatazz that has marked the birthday of Charles Dickens, who was exactly three months his senior.

The reason lies not in the fact that Browning wrote dense and difficult poetry. It is to do with his life. In 2012 we love celebrity, and we like our celebrities to have dash and drama. A tough childhood, a manic character, a secret mistress and possibly even a lost love child – all of these things make Dickens attractive.

Browning, by contrast, seems steady. But he too had a complicated life. In his youth he committed himself to poetry, refused to get a proper job and lived quietly with his parents in the village of New Cross.

Then, in his early 30s, he discovered the work of a fellow poet – "I love these verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett …. and I love you too." Of course he should have knocked on the door of 50 Wimpole Street and presented himself to Elizabeth Barrett's father. Instead, Browning agreed to a secret marriage and flight to Italy. Worse, there was the huge risk to Elizabeth's frail health. She soon become pregnant, and suffered a miscarriage at five months. When it was all over, and Browning was finally allowed to see his wife, he flung himself down in tears of remorse.

In 1861 Robert had to remake his world after Elizabeth's death. Twice he came near to marrying again, but in the end remained a widower for nearly 30 years, Elizabeth's ring on his watch chain. He devoted himself to his rather hopeless son, getting him into Oxford, he looked after his sister Sarianna and saw his father through various scrapes with women.

And he worked. He produced many of the long narrative poems that still intrigue scholars, but he also wrote lyrics that endeared him to the admiring young men and women who formed the first Browning Society in 1881.

Even now, many of his most famous lines come easily to mind: "'Grow old along with me! / The best is yet to be"; "O lyric love, half angel and half bird / And all a wonder and a wild desire"; "God's in his Heaven / – All's right with the world".

Browning never was poet laureate. The closest he came was in 1850, when Wordsworth died. Then it was suggested that it would be a suitable compliment to Victoria to propose a woman poet for the post, and that Elizabeth Barrett Browning should be that poet. "Besides", they said, "that way you get two for the price of one."

Now – at last – we do have a woman poet laureate. And Carol Ann Duffy's brilliant 2006 collection Rapture takes its title from one of Robert Browning's poems: "That's the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over, / Lest you should think he never could recapture / That first fine careless rapture!'

Just months before he died in December 1889, a representative of the new Edison company made a recording of Browning's voice on a wax cylinder. So Browning can still be heard from beyond the grave. But his real voice is in his poems and letters. Late in life he worried about privacy and burned many of his papers. But he could not bear to destroy the letters he had exchanged with Elizabeth in the two years of their courtship, and their son published them after Browning's death.

Browning is not flashy and highly coloured, like Dickens. He was short, a bit plump, he spoke too loudly. But he was a great poet, and his ordinary bravery makes him a hero for all time.

• Follow Comment is free on Twitter @commentisfree