It was, as Peter Bergen points out in this meticulously reported, pacy and authoritative book, the most intensive and expensive manhunt of all time. The hunt for Osama bin Laden, founder of al-Qaida and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, cost, simply in terms of funds funnelled to American intelligence services over the past decade, somewhere around half a trillion dollars. At its heart was an astonishingly small number of CIA operatives, no more than would fill a small conference room, and an equally restricted group of senior policymakers.

Many have spoken to Bergen, a former television journalist who has a justified reputation as one of the most reliable and perceptive specialists in the now expansive field of "al-Qaida studies". One of the strong points of this excellent account of how Bin Laden was found and killed is much new detail. Bergen managed to get himself into the house in the northern Pakistani city of Abbottabad where Bin Laden lived from around 2005 – a significant scoop – and can thus tell us how the militant leader, his three wives and his many children and even grandchildren spent their time in hiding.

We learn, for example, that Bin Laden's two older wives, both academics, taught the children Arabic and read from the Qur'an in a bedroom on the second floor. Almost every day, apparently, the al-Qaida leader, a strict disciplinarian, lectured his family about how the children should be brought up. Nor were Bin Laden's living conditions particularly salubrious. A tiny bathroom off the bedroom he shared with his Yemeni third wife had green tiles on the walls but none on the floor, a rudimentary squat toilet and a cheap plastic shower. In this bathroom, Bergen tells us, Bin Laden (54 when he died) regularly applied Just for Men dye to his hair and beard. Next to the bedroom was a kitchen the size of a large closet, and across the hall was Bin Laden's study, where he kept his books on crude wooden shelves and tapped away on his computer. There was no air-conditioning.

Such details are important in part because they remind us that Bin Laden, for all the monstrosity of his views and acts, was human. There have been times in the past decade when the Saudi-born son of a construction tycoon and veteran of the Afghan war has appeared more myth than man. Bergen neatly skewers hyperventilating analysts who spoke of world war three or four, reminding us that Bin Laden, al-Qaida and contemporary Sunni militancy were never an existential danger to our societies and values in the way that previous threats have been.

Much of the first half of Manhunt consists of a useful account – brought up to date by new sources that have become available over the past 18 months or so and Bergen's own digging – of the early years of the hunt for Bin Laden. There are some nuggets of new information including a fascinating description of how rampant sexism within the CIA in the late 1990s stymied some analysts' efforts to attract attention to the growing danger posed by al-Qaida, and of later attempts to identify a bird heard chirping on one video recording issued by Bin Laden. (A German ornithologist was called in by the agency to try to identify its species and thus, perhaps, location.)

Bergen rightly points out how, by the end of the last decade, al-Qaida's brand had been badly tarnished and quotes documents captured in the Abbottabad raid that show how Bin Laden, increasingly out of touch with ground realities, even reflected on a new name for the organisation as part of a major relaunch.

After about a hundred pages, though already rattling along nicely, the narrative moves up a gear. Bergen describes how analysts assembled and matched a huge amount of information from multiple detainee interviews, from thousands of al-Qaida documents recovered on the battlefield or following arrests, and from open-source reporting.

Importantly, instead of mapping hierarchies, the hunters sought to build up a picture of horizontal connections. This new approach – part of a more general paradigm shift in terms of how militancy was understood – was critical.

Focusing on connections and links, rather than apparent ranks, meant different people were highlighted. These might be lowly in status – such as a driver – but high in significance within an organisation. In Iraq this helped with the hunt for the brutal Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was eventually tracked down and killed north of Baghdad in 2006.

In the case of the hunt for Bin Laden, the person that interested the hunters was a Pakistani who had grown up in Kuwait, who appeared to be some kind of fixer for al-Qaida. Nobody knew exactly what he did, but the efforts of senior captured militants to downplay his importance to al-Qaida set off alarm bells at the CIA. The analytical case that "the Kuwaiti" might be the key to finding the al-Qaida leader was first made in a memo by CIA officials in August 2010 titled "Closing In on Osama bin Laden's Courier". A month later, a second more detailed assessment titled "Anatomy of a Lead" was put together. By this time, Pakistani CIA "assets" had located him in the border town of Peshawar and had trailed him back to the Abbottabad house.

The house was put under surveillance. The CIA worked out from washing strung up that there were at least three women, nine children and a young man living there. Then there was the "pacer", the apparently tall figure who was seen walking in circles in the walled garden. Yet, despite their efforts, the final conclusive identification never came.

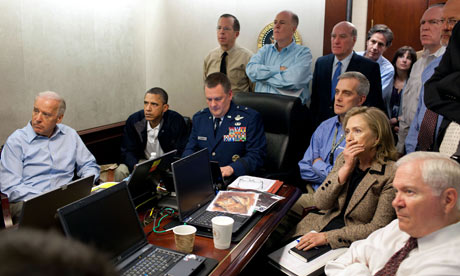

Instead, the hunters were reduced to probabilities. President Obama was briefed increasingly frequently. Some said there was a 40% chance that Bin Laden was there. Others went as high as 80%. But, in the end, it was all subjective. This makes Obama's decision to risk his presidency on a raid by special forces flying in from Afghanistan – not a stand-off missile strike or any of the other options available – all the more impressive.

So, on a Sunday night just after midnight, the residents of the Bin Laden compound were woken by explosions, says Bergen, basing his account on interviews with Pakistani intelligence officers who themselves interviewed Bin Laden's wives. Bin Laden's 20-year-old daughter Maryam rushed upstairs to her father's top-floor bedroom to ask what was going on. "Go downstairs and go back to bed," she was told.

"Don't turn on the light," Bin Laden then said to his wife Amal. These, Bergen says, would be the al-Qaida leader's last words.