In his book Darwin's Dangerous Idea, philosopher Daniel Dennett popularised the idea that evolution by natural selection was a "universal acid". The idea of evolution, he argued, ate its way through everything, destroying our familiar notions and convictions, leaving all transformed in its wake.

The Prince does something similar – with humanism, Christianity, political practice, traditional virtues, even mirror-for-princes books. But nowhere is the book's perspective more corrosive than in its view of human nature.

Machiavelli makes Hobbes look like a naive, philanthropic optimist. His opinion of human nature is eye-poppingly low. People are fundamentally self-interested and unreliable. "Men are quick to change ruler when they imagine they can improve their lot."

They are stupid and irrational, incapable of knowing what is actually best for them. "Men are so thoughtless they'll opt for a diet that tastes good without realising there's a hidden poison in it."

Their lives are marked by chasms of hypocrisy into which naive and unwary rulers are liable to fall. "There is such a gap between how people actually live and how they ought to live that anyone who declines to behave as people do … is schooling himself for catastrophe."

They are greedy, "a man will sooner forget the death of his father than the loss of his inheritance"; shallow, "all men want glory and wealth"; ungrateful, "since men are a sad lot, gratitude is forgotten the moment it's inconvenient"; credulous, "people are so gullible and so caught up with immediate concerns that a conman will always find someone ready to be conned"; and manipulative, "men will always be out to trick you unless you force them to be honest".

All in all, human nature offers little to inspire. "We can say this of most people: that they are ungrateful and unreliable; they lie, they fake, they're greedy for cash and they melt away in the face of danger."

This could not have sounded more discordant to an age schooled to believe in mankind's awe-inspiring, creative potential. It seems better suited to our own, lived as it is in the shadow of humanity's towering inhumanity.

But The Prince's view of human nature is more modern than its cynicism alone suggests. Throughout the book, Machiavelli blurs the boundaries between the human and the animal. Comparing humans with animals was an ancient custom, the virtues of strength, cunning, hard-work or even self-sacrifice being apparently evident in nature and eminently worthy of human contemplation.

Machiavelli does something slightly different, however, by talking in broad terms about human and animal nature, and arguing that the wise leader will "draw on both natures". "Typically, humans use laws and animals force," he observes. "But since playing by the law often proves inadequate, it makes sense to resort to force as well." A successful ruler "must be able to exploit both the man and the beast in himself to the full."

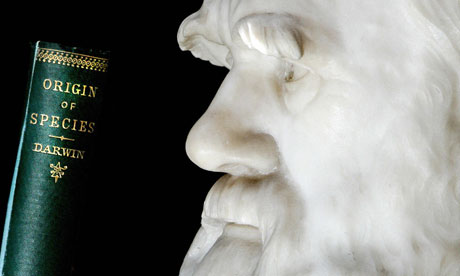

Once again, this constituted a rude challenge to contemporary humanist pretensions regarding human nature. But it also has a peculiarly post-Darwin ring to it, something that is compounded by Machiavelli's insistence that it is not constancy that brings success in a leader, but adaptability: "the successful ruler is the one who adapts to changing times."

This is, of course, nothing beyond historical accident. Machiavelli no more anticipated the theory of evolution than he did the theory of relativity. But it is a noteworthy accident, nonetheless.

The way we view human nature shapes the cultures we construct, as Roger Scruton's latest book, The Face of God, illustrates. The tussle between the person and the creature, the subject and the object, the angel and the ape, the human and the animal, as various generations have described it, is as old as there are written records – for the simple reason that neither side holds the winning cards, and the two natures wrestle, like Jacob with his angel, within each of us.

For Machiavelli, immersed in brutal, deceitful realpolitik of his age, it was clear which side of human nature dominated and thus equally clear how a ruler needed to rule. Ultimately, if your view of human nature is fearsome and unlovable, you are bound by honesty to advise that "it's much safer to be feared than loved".

• Follow Comment is free on Twitter @commentisfree