As China's Zhou Enlai would say, it's always too early to predict the outcome of a revolution – but wherever it's headed, the one that's happening in the publishing world looks to have reached a point of no return.

This week, the Publishers Association Statistics Yearbook – collating information from 250 publishers – announced that ebook sales in the UK had increased by 366% last year. Meanwhile, JK Rowling's Pottermore sold more than £1m of ebooks in its first three days of trading, and has had a billion visits to the interactive website since it opened to all-comers three weeks ago.

One of the less trumpeted innovations of the Pottermore experiment is that Rowling has waived digital rights management for her ebooks – which means they can be shared across multiple devices. The world's biggest science fiction publisher, Tor, followed suit, in a move that has been welcomed by champions of open access as "tearing up the rulebook", and will be watched beadily by more conservative players fearful that it will also tear up defences against ebook piracy.

So a lot is happening but what does it all mean? Much of the focus of the e-publishing debate in recent months has been on the ingenuity of writers such as Amanda Hocking, who muscled her way into a conventional publishing contract by demonstrating that there was a mass readership for her self-published novels of the paranormal.

Admirable though Hocking and her kind are in commercial terms, nobody would claim they are changing the aesthetic landscape – and a lot of the ebooks published so far are just digital versions of traditional codex books. But in literary terms, too, a revolution is under way.

Last week, the independent publisher Profile launched an updated, interactive version of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which leapt straight into the top 10 in the books section of Apple's App Store on both sides of the Atlantic.

The point about Frankenstein – and other innovative ebooks – is that it is a new type of monster, one that would be impossible to create within the pages of a paper book. Created by a writer with a background in video games, the reader can influence the route the story takes by making choices in the character of the monster or of Frankenstein himself. Because it deals with multiple pathways, Dave Morris's new text is longer than that of the original novel.

Another departure is promised for the end of the month, when the "enhanced ebook" of a new work by Ewan Morrison is released. Tales from the Mall takes its structure from the floorplan of a shopping mall. It mixes history with sociology, reportage with fiction. Anecdotes are repeated in print and on video, creating a text that can only be fully appreciated by "reading" both versions.

The educational potential in the new technologies is nowhere more apparent than in Faber's iPad app of TS Eliot's The Waste Land, which became one of the pace-setters on its release last year and took just a month to make back its production costs. It offers the treat of reading this difficult modernist poem in a specially designed digital typeface while listening to your favourite archive performances – from Alec Guinness, Ted Hughes, Fiona Shaw or Eliot himself. You can puzzle your own way through Eliot's manuscript and Ezra Pound's edits, or seek help from experts such as Seamus Heaney or Jeanette Winterson, who share their thoughts on video.

However, no innovations come without health warnings – and a recent article in Time Magazine suggested that digital reading might damage your learning. It quoted Kate Garland, a psychology lecturer at Leicester University, whose studies on memory and digital reading appeared to show that the human brain doesn't navigate digital texts as efficiently as paper ones. Her findings suggested that computer readers needed more repetition to absorb the same information as from a book, and that book readers seemed to digest the material more fully.

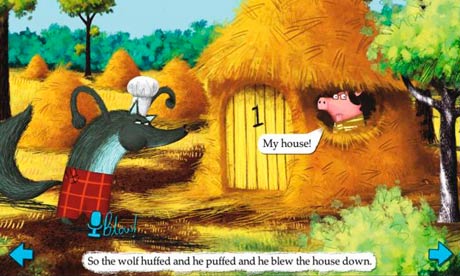

But Garland's experiments were carried out on students whose brains had been trained on the printed book – and it is in children's books, particularly for the youngest readers, that much of the innovation is happening. Today's three-year-olds don't just read about the three little pigs, but can huff and puff and blow the house down.

In all the excitement, though, it's worth bearing in mind that, even in children's books, not all innovation is digital. Coming shortly, thanks to a "ground-breaking new technology based on micro-encapsulation and touch activation", is a range of books that will smell of their subject. And which do we think will be most successful with the digital natives of tomorrow? Why, The Story of the Famous Farter, of course. Some things never change.

• Follow Comment is free on Twitter @commentisfree