A big, beautiful book of intimate photos of women from Sierra Leone, Liberia, Sudan, Kenya, Brazil, India, Cambodia: you'd expect these portraits to describe tales of horror and hardship, and they do. There's a 13-year-old girl from Liberia who recalls her repeated rape during the civil war; a desperate mother of four confessing: "I want to give the baby that I am breastfeeding to people for free, because I have nothing." There's the opposite, too: a businesswomen from Nairobi's Kibera district proudly details how she makes and sells chips, and exhorts other women not to waste their lives waiting for men who have died, disappeared or abandoned them.

But what sets this work apart is the life the portraits acquire after they are taken. For French "urban artivist" JR, and winner of last year's TED prize, photographs are only the beginning of the creative process. Working with a huge team (more than 100 for this project), he pastes enormous posters of the captured images in public spaces all over the world – on the walls of churches and mosques, the sides of buses, trains, favela walls and stairwells, on the bottom of an empty swimming pool. Sometimes the person pictured has an intimate relationship with the location; one woman he met had escaped a life sifting through rubbish in an acrid dump on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. She took him back there to show him it, and eventually allowed her photographed eyes to be pasted to the side of a rubbish truck, so that her gaze now looks out at the life she left behind. Other times, the choice is a simple response to an obvious need: the post-election violence that swept Kibera left many houses without roofs, so the team put up tarpaulin with the eyes of residents printed on them.

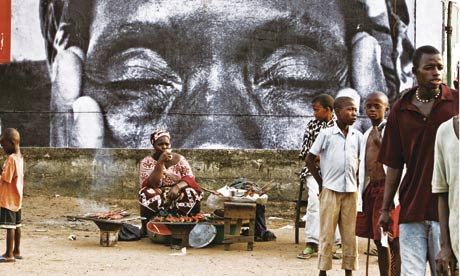

The book, then, is both a series of portraits, and portraits of portraits: of photographs taken in Phnom Penh, New Delhi, Rio de Janeiro, New York and elsewhere which show the images transposed on to urban landscapes, and often capture the reactions of passers-by. JR and his team never stick to one medium. Sometimes (as in India) they stencil the outlines of images on to the side of buildings, so that they only begin to take shape when dust has settled on them; other times they project stills or video installations on to landmark pieces of architecture. And while this project is a celebration of the heroism of women living through hardship, men aren't absent either; we catch glimpses of tough guys in Rio's favelas looking on as the volunteer artists work, and of children reacting to the art that has suddenly popped up in the urban landscape.

It would be easy to be cynical about what the foreword calls "Participative Art or Art 2.0" (the latter moniker should be banned). But the work's beauty and power is undeniable. When one onlooker in Monrovia didn't know what an art exhibition was, another person explained it thus: "You have been here for a moment looking at the portraits, asking questions, trying to understand. During that time, you haven't thought about what you will eat tomorrow. This is art."