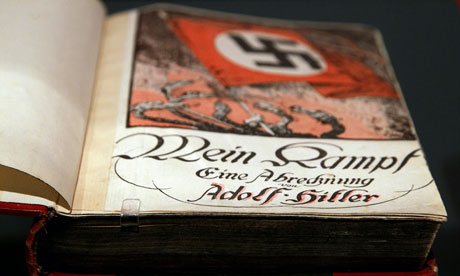

The decision by the Bavarian state to bring out a carefully annotated edition of Hitler's Mein Kampf – before the copyright expires in 2015 and anyone can publish the book – is sensible and laudable. At least in a German context. But this will have no effect on the readers of the thousands of badly translated, unedited copies that are sold around the world every week without so much as a warning that Mein Kampf can poison your mind. Indeed, young Germans are the last people who need to be inoculated against the hatred it preaches. Germany's bomb-fractured urban landscape and the countless memorials to its war dead are a potent antidote to Hitler's rhetorical belligerence and recipe for territorial expansion.

Even outside Germany it is an open question whether Hitler's rant still has much practical appeal. The first part comprises his reminiscences, carefully sculpted to suit his purposes as an aspiring politician in Weimar Germany. His nostalgia for the trenches, his rage against the "November criminals" who engineered Germany's capitulation, and his tirade against the Treaty of Versailles can hardly inspire politicians of any stripe today. The second part, which outlines the ideology and tactics of the National Socialist movement, is similarly archaic.

Indeed, Hitler's politics rest on contempt for almost every tenet of activism that the present far right espouses. Individual rights, consultation, democracy, decentralisation, devolution: all these merit his scorn. Hitler reserves his most violent language for what the far right today would consider the wrong targets. There is no mention of mass immigration, Muslims, diversity or, of course, the European Union. His attacks on communism and Marxism are now largely irrelevant. If Hitler had seen the BNP's slogan, "Democracy, Freedom, Culture and Identity", he would have reached for his Luger.

The ideology embedded in Mein Kampf represents the antithesis of the politics spawned by social media. In his nostrums on propaganda Hitler derides the masses and individual choice. People should be told what to believe. They need a strong leader. He exudes loathing for the weak, the disadvantaged, not to mention the physically disabled. Mein Kampf is not a primer for the "I feel your pain" approach that every politician necessarily practices these days.

Yet this hardly means that all Hitler's venom has been neutralised. Mein Kampf remains a ticking bomb because of the one element that has remained evergreen: hatred of Jews. Ironically, though, Hitler's murderous antisemitism is least likely to appeal to the followers of the modern far right. Throughout Europe, its leaders have sweated to shed the legacy of Nazi genocide against the Jews and to remove the stigma that anti-Jewish policies attached to fascism in all its varieties.

On the contrary, the ideologues of the far right are more likely to use abhorrence of Nazism for their own, quite different political ends. For example, in 2010, Geert Wilders, the leader of the Dutch Freedom Party, compared Mein Kampf to the Qur'an. The racism that propelled Hitler's social and political thinking has been refocused by the far right in contemporary Europe and North America.

Instead, Mein Kampf is more likely to gratify those disposed by circumstances to see Jews as a powerful, manipulative global presence. The conflict between Israel and the Arabs created an appetite in the Middle East for any explanation of Jewish behaviour no matter how fantastic, malign or tainted. Mein Kampf was first published in Arabic in 1963 and there have been a number of editions since then, often abridged, some with glowing introductions. It can be found in bookshops throughout the region. The book was popular with members of the Syrian Ba'ath party in the 1960s.

Mein Kampf was the most concentrated distillation of 19th-century racism, social Darwinism and "racial-biological science", but these toxins have been largely worked out of the body politic since 1945. Or they have been cunningly reformulated by true believers in such a way that Hitler's language barely connects with the new slogans of the far right. However, Mein Kampf also crystallised the antisemitic discourse of the era and raised the myth of a world Jewish conspiracy to a new pitch. In many parts of the world that discourse is acceptable and used in everyday politics without apology. It is here that Mein Kampf will continue to wreak havoc on human rights, democracy and liberty. Tragically, judicious commentary by conscientious German academics will not make any difference to that.

Exposing Germany's school students to Mein Kampf may do some good, though. After the war, Germans quickly recast themselves as victims of National Socialism. Successive generations have imbibed this notion, along with the watchwords "never again". Exposure to Hitler's manifesto may at last undermine such an assumption. Young Germans may start to wonder whether the millions who read Mein Kampf and still voted Nazi or supported Hitler can truly be regarded as "victims" of all that followed from his rule.