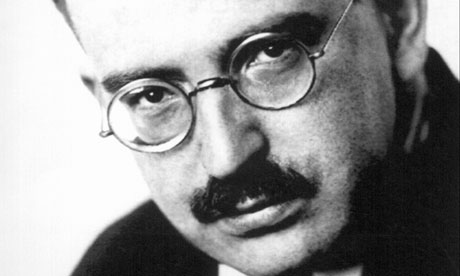

I was a student in college when I first starting reading Walter Benjamin. Literary critic, philosopher, essayist, he was a man of words. As a German Jew he had been born in turbulent times, at the end of the 19th century, and in the most dangerous of places, Berlin.

While he was known only to a limited audience during his lifetime, his fame rocketed after his death. I remember waiting impatiently for the Turkish edition of the Arcades Project. The book travelled everywhere with me in my backpack; its pages torn on the edges, dotted with cigarette burns and coffee stains, and once, during a rock concert, soaked in the rain. Among all the books I read that year, fiction and non-fiction, no other was so tattered, so deeply loved.

Benjamin was an alchemist of sorts, the most unusual of Marxist intellectuals, a black sheep in every flock. He merged literature with philosophy, the questions raised by religion with the answers provided by secularism, left-wing opposition with mysticism, German idealism with historical materialism, despair with creativity … He was an expert on Goethe, Proust, Kafka and Baudelaire, but he also wrote extensively on about the small, ordinary things in life. He was no philosopher of ivory towers. As you keep reading him you can almost watch him strolling the streets, listening to people, taking notes, making sketches, constantly collecting.

One doesn't read him to feel better. One reads him to feel. In his universe nothing is as it appears to be and there is a vital need to go beyond surfaces and connect with humanity. To live is to walk upon a pile of rubble, listening to any signs of life coming from under the ruins. Melancholy constitutes an intrinsic part of his existence. One evening a nihilist boyfriend got drunk and yelled at Benjamin's photograph on the wall: "Smile Mr Walter! Don't need to carry the world on your shoulders. You are dead now, relax!" He then flung his wine glass at him, which he probably wanted to throw at me. I cleaned the mess with dishwashing soap, but a stain remained on Benjamin's glasses, making him see everything through a lens of red.

God, progress, civilisation, there was nothing he could not doubt, least of all himself. He was so modestly uncertain, this man of towering intellect. Gershom Scholem, the fountainhead of Jewish mysticism, thought Benjamin was a most special soul but why on earth did he converse with those leftists? Brecht had a profound respect for him but never understood what he was doing around those mystics. And in between two worlds, translating the words of those who never spoke the same language, Benjamin stood on his own, beautiful in his loneliness.

As the Nazis consolidated their power and humanity exchanged reason for madness, harmony for bigotry, he had to flee his homeland, this man who could not live away from his library. The journey across Europe was full of perils. On 26 September 1940, he committed suicide on the Franco-Spanish border while waiting for his visa to be granted. Suddenly he had decided to wait no more, doubt no more.

• Elif Shafak's Honour is published this month by Viking.