Reviewers will often say a book made them laugh out loud, when what they mean – funny books being so bafflingly thin on the ground – is that it made them smile; their exaggeration is a symptom of their relief that it even did that. But Skios, Michael Frayn's new novel, his first for 10 years, truly does make you laugh out loud. I sniggered on the train and the bus; I sniggered in the kitchen, the bedroom and, on one occasion, in the shower. I wasn't reading the book in the shower, obviously. But I was thinking about it, and that was enough. Skios, which stars a pompous academic called Dr Norman Wilfred, a shambolic bounder called Oliver Fox, and something called the Fred Toppler Foundation, organiser of an annual thought-fest for rich people – it's like the World Economic Forum at Davos, only without the snow, the balance sheets or Stephanie Flanders – really is hilarious.

"Oh, good," says Frayn, when I tell him this. "I'm glad. It is a bit of an experiment. I wanted to see if you could do farce as a novel. In the theatre the audience is released by the laughter of the people around them. But with a novel you have an audience of only one; no corporate reaction." He pauses. "Of course, at this stage [in my career] self-plagiarism is a terrible danger. I realised recently that Skios is slightly similar to a film I wrote, Clockwise [starring John Cleese]. Though things in Skios go wrong for different reasons. The other difference is that, with a novel, you do need to know what the characters are thinking. You need to know what Oliver Fox thinks he is up to, which is, frankly, not very much."

This is true – though it's the unreliable Fox who sets the dominoes falling when he lands on the Greek island of Skios for a romantic assignation. On seeing a taxi driver holding a sign that reads "Dr Norman Wilfred", Fox decides – who knows why? – to pretend to be him, a move that provides him with the chance to enjoy a little of the Fred Toppler Foundation's hospitality, and to deliver its keynote speech. Meanwhile, on the other side of the island, a lovely young woman called Georgie Evers discovers, to her horror, that the man who has been delivered to her villa is not the gorgeous Oliver Fox but a balding, slightly podgy fellow called Dr Norman Wilfred.

"It had been in my mind for a while," says Frayn. "Every time I arrived at an airport and saw the line of people holding up cards, I thought: what would happen if I went up to one of them? How far would I get?"

It's probably not giving too much away to say that Fox gets a very long way indeed. He is… deluded! "He saw his life as Dr Norman Wilfred stretching in front of him like the golden pathway into the rising sun," writes Frayn. "He had no choice but to walk along that pathway, towards the warmth, towards the light."

Where did this Oliver Fox come from? "Well, there is a touch of a real person in there," says Frayn. "John Gale, a wonderful reporter at the Observer. When I was a student I passionately admired him. He wrote these extremely cool, offbeat pieces. I desperately tried to imitate his style, quite unsuccessfully. When I joined the Observer, I met him. He was a manic depressive; in the end he killed himself. But his manic phases were extraordinary. He once told me he'd been walking down Fleet Street when he realised that the car next to him – the traffic was slow-moving – had white ribbons on it. He could see the happy couple sitting in the back and he knew – he just knew – that what they wanted him to do was to get in. So he did. He sat and chatted quite happily. He had that absolute certainty. There's a bit of that in Oliver."

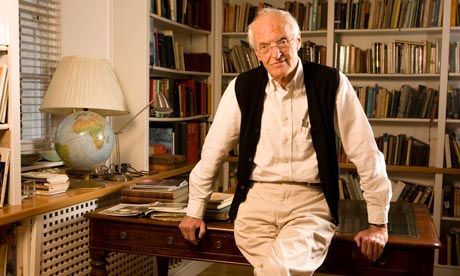

Frayn, who will be 80 next year, always tells interviewers that his current book/play/memoir will be his last. "I'm never going to write anything ever again," he says to me, mock solemn. He and his wife, Claire Tomalin, are enjoying the quiet after the storm (her biography of Dickens was published last year); neither of them has begun a new book yet and the atmosphere is "quite jolly – we get a bit monosyllabic when we're both writing".

But it's impossible to imagine them not working – and sure enough, in the next breath, he reveals that he has been rewriting parts of his 1993 play Here which, by the time you read this, will have opened at the Rose Theatre, Kingston (meanwhile, the Old Vic's ace revival of Noises Off continues in the West End). Isn't work his engine? "Well, if you haven't got a job, it's difficult to retire. I've sometimes thought that I should go out and buy a clock and present it to myself. It does seem a bit improbable [to be almost 80]. An elderly actor was once asked what it was like being old. He said: it's like being young but having a lot of slap on your face. I've got quite a bit of slap on my face. But it doesn't feel any different internally."

Frayn's last book was a memoir of his childhood, My Father's Fortune – that was another thing he used to say: that he'd never write about himself. "I intended to write about my father [who was a funny, kind and deaf asbestos salesman] but I found I had to write about myself because part of his experience in life was having a son and finding ways to get on with him." I wonder what he feels about this book two years' on; I think it's a masterpiece. "One of the sad things about writing non-fiction is that it moves you still further away from the original events. I wrote it as truthfully as I possibly could but, looking at it now, I wonder if I made the whole thing up. I'm glad I did it. But it was emotional. People said afterwards: have you achieved closure?" He snorts. "I would say: absolutely not! It just stirred all the feelings up again…

One of the nice things, the terrific things, was that I got letters: from people who recognised something of their own family life but also from people who knew my father. The most wonderful was from someone who'd been in the next hospital bed to him when he first had cancer. My father had been having a rough time, he was in great pain, but this man – a student who'd had his appendix removed – said that my father realised he was homesick, and kept an eye on him." His eyes fill with tears.

A while ago a friend of Frayn's told the New Yorker that he and Tomalin were living an idyll – and this is how it looks from the outside. Their house close to the Thames in Petersham is luxuriantly light and organised; their lives are replete with work and family (between them they have six children and 10 grandchildren); the painful things – Frayn was married when he fell in love with Tomalin – are now in the past. Is this how it feels? An idyll? "No!" he yelps. "Wherever you live, however you live, there's still the weekly shopping to do, the computer to fix." The Russians, he says, have a wonderful but impossible-to-translate word for this stuff – the exhausting logistics of life. He says the word, and then he spells it, for the benefit of my tape. But when I get home I can't hear either – and when I Google it, I'm offered the chance to buy a mail order bride. We sort this out by email later: it transliterates as "byt". But Google's misunderstanding is, I think, quite delicious, it being exactly the kind of thing that happens on the strange and bewitching island of Skios.