The Isle of Wight is different. And though it stands within teasing sight of the mainland, jagged needles of white rock trouble the casual visitor, making that small separation feel like a tide of rising panic, the nagging anxiety of a road that is too empty; retirement houses and curtained bungalows so self-contained they speak of thunderhead psychoses, imminent breakdown. Coming here in 1995 to record David Gascoyne for a poetry event at the Royal Albert Hall, when he didn't have the stamina to join Allen Ginsberg, Sorley MacLean and Paul McCartney, my companion said: "This is like finding yourself in a Look at Life film. Being trapped in the 50s when they started to use colour but didn't know what to do with it." The island, once a gulag for the extended mourning of Queen Victoria and her shaggy laureate, Alfred Tennyson, uses the glittering sea lanes between Ryde and Portsmouth as a manifestation of that difference: as between poetry and prose, elective exile and the humdrum business of ordinary mainland existence.

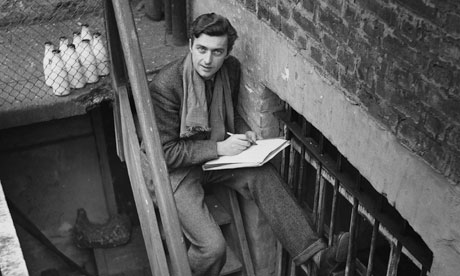

The legend of how Gascoyne was brought back from the dead, to be given a last act of domesticity and a measure of grudging cultural acknowledgement is reprised in Robert Fraser's painstaking biography. Here was a fragile personality, a premature revenant, on the fringe of all the movements. An autodidact blessed like his peers – Dylan Thomas, George Barker, David Jones – in avoiding a university miseducation. A convinced internationalist (last wave of high modernism in Paris, first wave of speed-freak meltdown in the US), Gascoyne was the poets' poet, subsisting on the wrong kind of patronage: the patronising reviews of Stephen Spender rather than the munificence of Joycean benefactors, adulating Left Bank paymistresses and New York manuscript collectors. A tall, thin, nicely spoken lad, gone in the teeth, sexually unfocused, in thrall to the dangerous virus of language, Gascoyne, the former Salisbury choirboy, travelled the blacked-out cities and hamlets of wartime England as a jobbing repertory actor, when the other bright young men were away in uniform.

In the complex progress uncovered by Fraser, Gascoyne's history becomes a witnessed romance of manners and slights, a landscape in which cold biographical facts are converted into metaphors of questing vision, delirium, breakdown. The gaberdine England of slow trains, drowned fields, damp boarding houses, clamps the poet in a stifling embrace. Gascoyne is a cross-channel man, an importer of surrealism and a compulsive tourist in painters' studios. "Is it true that you actually knew Max Ernst?" demands a persistent interviewer, stalking the poet's stair-lift retreat, on the outskirts of Newport. "Knew him? I had him over the back of a grand piano in 1926."

Fraser's fable of a poet's life, the impossibility of that role in a society that has no use for it, moves chronologically, set piece by set piece, through the decades of the last century. Gascoyne was born in 1916 and died just after the new millennium. He grew up in a female-dominated household – his father away at war – and in a setting that provided the ideal preparation for his later engagement with surrealism. The Cartesian weirdness of Magritte translates effortlessly into the community of women at Harrow in which Gascoyne lived for his first few years. (Harrow was where another troubled seeker-poet, David Jones, made his long retreat, turning his room into a version of a first world war trench, heaped with books, papers, pens and prayers.)

Winifred Emery, Gascoyne's mother, came from an established theatrical dynasty. As a young woman, she was in the private lake of WS Gilbert (of Savoy Opera fame) when she found herself struggling, out of her depth. Gilbert, trying to reach her, slid beneath the surface and drowned. Also in the bathing party was Ruby Preece, who later changed her name to Patricia, before becoming a student at the Slade and captivating the painter Stanley Spencer, with whom she lived in spectacular disharmony in Cookham. Such are the collisions and coincidences of sociocultural intercourse on our small island. And Fraser is diligent in highlighting them.

Without labouring the thesis, he manages to suggest that Gascoyne's lifelong interest in conspiracy, covert sexuality, the occult, is an extension of the rituals and disguises of London suburbia. Poems, on the edge of self-erasure, fret over the impulse that pushes them towards publication and exposure. The visionary poet, a Christian existentialist, was prolific in his silences. He contrived enough white space for others to mythologise a consistently aborted career. He traded in the distance between his own reluctant muse and the conviction and swagger of the great ones he sought out, echoed and honoured.

The tension, when Fraser draws on the Paris journals, is palpable; at times this biography is a form of channelled ventriloquism, a paraphrasing of Gascoyne's private letters to himself. English poets have been defined by crumbling mouths and the inability to drive. Think of old Auden shuffling around Oxford in carpet slippers, his trenched stocking-mask face a microwaved photograph of ruined youth. Think of Dylan Thomas, in a New York bar, covering his rictal grin with a damp cigarette and a cheekful of boiled sweets. Persistent toothache, as much as boredom and dread, brought Gascoyne to his drug habit: the destructive quest for a form of reverse alchemy, glitter to mush, as he peeled the innards of the benzedrine sulphate inhalers that came in gold-coloured cylinders. Amphetamine psychosis fired the motors, fuelling the poet on nocturnal walks through the city, but brought him to sleeplessness, stalled inspiration, voices in the head. After a manic episode, breaking into the Elysée Palace to warn De Gaulle of the coming apocalypse, Gascoyne was institutionalised, and spent years drifting between impoverished retreat and melancholy incarceration, one of the nameless reforgotten.

Biography, which is part of the process of resurrection for a reputation, comes in three forms: as a commissioned text by a strategic bounty hunter, as a book catalogue (market value), or in the poet's own words – the story as he wanted to deliver it. Gascoyne's rescue, his return to life in the suburban house on the Isle of Wight, was brokered by two remarkable people. Judy Lewis, a vet's estranged wife, who read his "September Sun: 1947" to a depressed group at Whitecroft Hospital, provoked the previously mute writer to speech. "I am the poet." "Yes, dear. I'm sure you are." But it was true. He was the poet and it was always 1947. He became a living quotation recovered from a midden of fragments: "All our trash to cinders bring." There was to be a notable late flowering for the willowy and disconsolate figure in the bow tie, the time traveller from the 30s. Gascoyne married Judy. He had found his loving companion and chauffeur.

The second figure in Gascoyne's rebirth was an East Finchley bookman, Alan Clodd – dealer, publisher, collector. Clodd, grandson of Thomas Hardy's friend and banker Edward Clodd, was the George Smiley of English letters. A hovering, owlish figure in a short white raincoat, gripping a bulging attaché case, Clodd pounced on the Gascoyne journals when they resurfaced. He excavated poems and elusive translations from libraries and locked cabinets. He understood well that bibliography offers as powerful a storyline as biography. And in this sense the catalogue of Gascoyne's own library assembled by James Fergusson as Every Printed Page Is A Swinging Door reveals as much of the truth as Fraser's substantial work of archaeology. Clodd, with his cancelled smile and his fastidious eye, was a private detective unpicking the past, trawling for value, and hoarding the evidence in his book-crammed museum-house.

In the last years, Judy and David became a double act. She prompted, he veered between benevolent silence and magnificent memory riffs, recalling Dr Karl Bluth who shot him up with a heady mix of ox blood and methedrine, conversations with Picasso and Dalí, sessions in New York with Ginsberg. October sunshine filtered through the branches of the cherry tree in the quiet garden, speckling a table laid with marmoreal segments of cake, as Judy trawled the photo albums. Tracking Fraser's sympathetic biography gives us a measure of that Isle of Wight experience; reading becomes listening, all the gaps in Gascoyne's hopping and skipping monologue are neatly filled.

Iain Sinclair's Ghost Milk is published by Hamish Hamilton.