Iran is the only country in the world where people think that secretly, behind the charade, America is Britain's poodle. The eponymous hero of the 1970s comic novel My Uncle Napoleon – which was turned into one of the most popular TV series ever shown on Iranian television – is affectionately parodied for this: whatever went wrong, Uncle Napoleon blamed the British. The reason lies in a historical period imprinted on the minds of generations of Iranians but long forgotten in the UK. Christopher de Bellaigue's elegantly written account of the life of the nationalist Prime Minister Muhammad Mossadegh, and the MI6/ CIA-led coup against him, not only tells the full story of what happened, but highlights the dangers of a foreign policy that ignores the perceptions of those with memories longer than our own.

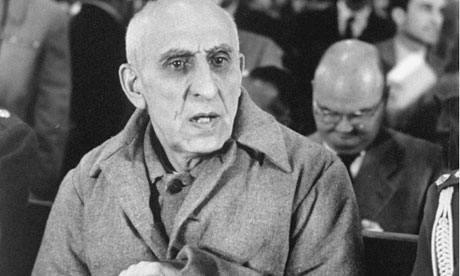

There have been several previous biographies of Mossadegh, but De Bellaigue – a Persian-speaking British journalist who lived in Iran and married an Iranian – has written a book that feels both fresh and relevant, and has a foot in both the British and Iranian camps. Muhammad Mossadegh was a Persian nobleman, born towards the end of the 19th century, who, as prime minister of Iran in the early 1950s, nationalised the country's oil. This brought him into conflict with the British government, led by Winston Churchill, which, just before the outbreak of the first world war, had bought a majority stake in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, with its concession in Iran. Churchill thought that if Mossadegh's move was allowed to set a precedent, British imperial power would be under threat across the globe. At first the Americans were neutral, even inclining towards Mossadegh, but – in the Iranian version of events – the perfidious British persuaded them otherwise. Dwight Eisenhower, elected in 1953, feared that Mossadegh's liberalism would lead to communism. The coup involved the dark arts in which the British and American secret services excelled: disinformation, unleashing agents provocateurs, paying thugs and politicians and forging documents. The tragedy is that it worked. The most enlightened Middle Eastern government of the age was overthrown, ushering in first the dictatorial regime of the Shah and then Ayatollah Khomeini's Islamic Revolution.

De Bellaigue sees racism in the British attitude to the man Churchill nicknamed "Mussy Duck". Statesmen like Thomas Babington Macaulay saw "a single shelf of a good European library" as superior to "the whole native literature of India and Arabia". Such an attitude did not go down well in the land of the poets Rumi and Hafez, which had an empire when Britain was still inhabited by iron age tribes. Every now and then, an orientalist diplomat would reveal a romantic enthusiasm for things Persian, but De Bellaigue believes that "a profound contempt for Persia and its people" lay at the heart of British policy.

Yet he is not blind to the faults of his subject, whom he describes as "a peculiar man", a "mixture of visionary and fusspot" and a "shameless hypochondriac" who "fainted and howled in public". De Bellaigue writes with humour and attention to revealing detail, painting a picture of Mossadegh as a man of principle, who acted out of patriotism and a sense of justice, but who rarely hesitated to take to his bed with a fit of the vapours if he thought it politically expedient, and who, by the end of his time in office, acted against his own democratic values. He missed opportunities to compromise with the hated British which would not only have benefited Iran, but might have prolonged his government. Mossadegh failed in part because of his own complex, flawed character, and in part because he was ahead of history. Anglo-Persian went on to become British Petroleum. Twenty years later, when Middle Eastern oil producers, spearheaded by Colonel Gaddafi, nationalised oil assets and withheld supply to push up the oil price, BP might have recollected Mossadegh's terms with nostalgia.

For Iranians, Mossadegh's legacy is a pride in Iranian-ness which the current regime's trumpeting of Islamic over national identity cannot extinguish. Similarly, his treatment by the British has come to symbolise the effrontery of meddling foreign powers. De Bellaigue is careful not to make crass comparisons, but this is nonetheless a timely book. Whenever a British or American politician chastises President Ahmadinejad for his nuclear programme, and talks of "carrot and stick", even Iranians who loathe the current government, and disagree with its nuclear policy, recall Mossadegh and Churchill. It raises a disturbing question: will our current objection to Iran having a nuclear weapon one day look like Britain's 1950s horror at the idea that Iranian oil might belong to the Iranians and not to us? There are many reasons why not – but if you don't ask the question, you cannot understand the current Iranian government's negotiating strategy and rhetoric.

Lindsey Hilsum is international editor for Channel 4 News. Her book Sandstorm: Libya in the Time of Revolution will be published by Faber on 5 April