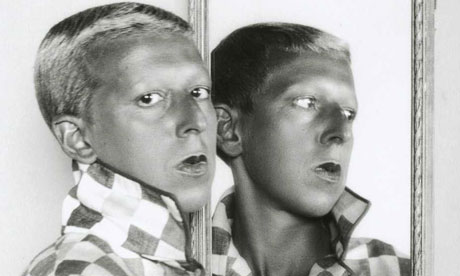

A writer born into literary royalty, with a pseudonym to hide the fact; a forebear of Cindy Sherman, with only one self-portrait published in her lifetime; a lesbian in love with her step-sister; a Jewish, Marxist Surrealist – Claude Cahun is probably the most complicated artist you and I have never heard of.

Born 1894, real name Lucy Schwob – her uncle was the great Symbolist writer Marcel Schwob – Cahun was educated at the Sorbonne, moved to Montparnasse in 1922 and spent the subsequent 16 years in the French capital. Pre-Paris, she fell for Suzanne Malherbe, the daughter of her stepmother, and the couple collaborated – to varying extents – on Cahun's literary and visual output over five decades.

With fascism on their doorstep, in 1938 they moved to Jersey – only for the island to become the one part of the British Isles to suffer Nazi occupation. In Paris, Cahun had played a major part in Georges Bataille's Contre-Attaque resistance group, and in Jersey she soon instigated an outrageous – not to mention dangerous – game of subterfuge, producing fake letters and tracts advertising unrest among the occupying forces. It was startlingly effective: two old cat ladies had the Nazis on the run, fearing mutiny. In 1944 they were finally found out, arrested and sentenced to death. The island was liberated just in time, but the effects of prison had taken their toll. Cahun was unable to return to Paris after the war for health reasons, and died in 1954.

More than half a century on, and 100 years after Cahun first seriously started writing, a new exhibition of her work is touring the world. Beginning in Paris at the Jeu de Paume last May, then moving to Barcelona in September, the exhibition will be in Chicago until June. It's her first major solo exhibition in over a decade, which, given her story, is astonishing.

Cahun effectively vanished from history. Her membership of the Surrealists and her political activities in Paris, her written texts encompassing, among other things, an attack on Louis Aragon, a French translation of Havelock Ellis's Woman in Society, a parody of Oscar Wilde's Salomé (the original of which her uncle had edited), and a vast array of self-portraiture – all of it was forgotten. It wasn't until well after Malherbe's death in 1972 that French writer François Leperlier was prompted to dig deeper. His subsequent biographical works are the only ones available, though Cahun's oeuvre has since become an intermittent battleground, with feminists and leftist art historians squabbling over her proper place in their respective narratives.

Why has she been so neglected? The question has troubled many a Cahunian (as the writer Lauren Elkin has termed them). After all, Cahun was one of the few women who actively participated in Surrealism during its most vibrant years. So why was she removed from the principle narratives – Surrealist, Lost Generation, women – of the era?

Friends with salonnières Adrienne Monnier and Sylvia Beach (Cahun even photographed the latter) she was nevertheless an outsider on the Parisian literary scene. She was close to founding surrealist André Breton – although when she and Malherbe would arrive at his favourite café, he would dramatically leave. The two may well have been diametrically opposed sexually, but intellectual poles attracted. Breton referred to Cahun as "one of the most curious spirits of our time" on publication of her 1930 anti-memoir Aveux non avenus (which, loosely translated, means "avowals not admitted" – or, as has since become convention, Disavowals).

And it's this work that provides the key to Cahun's lost status. Rejected by Monnier – Cahun had refused to write a commissioned "confession", and ignored her brief – the book was unclassifiable, even when compared to the sort of experimentalism that pervaded surrealist literature. Breton's Nadja (1928) opened with the line: "Who am I?" Cahun's Aveux, similarly, echoed this elusiveness of autobiography:

"No, I will follow the wake in the air, the trail on the water, the mirage in the pupil … I wish to hunt myself down, to struggle with myself."

The "anti-memoir" was, crucially, in stark contrast to another of its epoch: The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas, by "lost generation" membre principal Gertrude Stein. Written in the first person of Stein's pen-pushing lover, with the express purpose of declaiming its subject a "genius", the book even mentions Cahun – albeit pejoratively – as "the niece of Marcel Schwob". Pejorative, because her lineage was a burden; a sort of literary silver spoon that she could never spit out – even with a pseudonym.

For Cahun was a writer, first and foremost – and no amount of artistic squirming could change that. As W Somerset Maugham explained, "We do not write because we want to; we write because we have to." Indeed, Cahun was encouraged to write by all who knew her – most especially Breton. "It is essential," he wrote to her, "that you write and publish – you must keep telling yourself this."

It was, however, her dilettantism – a refusal to fit in, to be pinned down as "writer", "woman", "lesbian", and master her craft – that rendered Cahun a blind spot in the history of the last century. As she herself wrote: "Individualism? Narcissism? Of course. It is my strongest tendency, the only intentional constancy I am capable of. Besides, I am lying; I scatter myself too much for that."