It's both the best and worst of times to produce a Dickens biography. Best because (for anyone just returned from the further reaches of the galaxy) 2012 is the bicentenary of the great man's birth. Worst, because there's competition. In fact, Simon Callow's Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World is intriguingly complementary to Claire Tomalin's deservedly feted Charles Dickens: A Life. Callow has form as a biographer (Charles Laughton, Orson Welles), and as a memorialist and essayist. But he is a writer best known as an actor, and it's as such that he has taken on someone best known the other way round.

The front and back cover present Callow's thesis with a certain amount of chutzpah. Both consist of a cut-out of a Victorian gentleman standing on a toy theatre stage. On the front, the cut-out is topped by the book's subject's head, on the back, by its author's. On the second page of the book, Callow justifies his presumption. He has performed several Dickens stories on stage (most recently, A Christmas Carol), and played Dickens in a one-man play by Peter Ackroyd, and on Doctor Who. Quoting actor Warren Mitchell's response to the accusation that he'd changed a playwright's line, Callow hasn't just written Charles Dickens: "I've been 'im".

Being him, Callow describes the psychodrama of the great man's life persuasively: the ghastly year in the shoe-polish factory that gave Dickens his social anger, but also his iron will; the premature death of his adored sister-in-law Mary Hogarth, which led him to idolise women in his fiction and mistreat his wife in real life. Noting Dickens's "orotundities", Callow comes up with a few of his own: "noctambulistic researches into the condition of the people" are undertaken; Dickens's sartorial theatricality is "unfavourably animadverted on in some quarters". But the unique insights of Callow's book are not so much about Callow the actor's perceptions of Dickens but about Dickens the actor himself.

Conventional wisdom has it that Dickens was lucky to have been born into a showy but shoddy period for the British theatre (the playwriterly glories of the Sheridan and Goldsmith era were long gone). Had theatre been in the "high and balmy days" wistfully evoked by Mr Curdle in Nicholas Nickleby, then the passionate young theatre-goer might well have become a playwright, a calling for which he was clearly unsuited (the great William Macready – friend and dedicatee of Nicholas Nickleby – assured Dickens that his farce The Lamplighter was not worth putting on). Dickens clearly learned important lessons from the theatre: as Callow points out, he picked up his "streaky bacon" technique of alternating comic and tragic scenes from the dramaturgy of his day. He was a prodigious stage manager and producer of highly successful and sometimes commercially successful amateur dramatics. As Callow puts it, "literature was his wife, the theatre his mistress". But although Dickens wondered in later life whether "nature intended me for the lessee of a national theatre", posterity is generally agreed that he picked the right girl.

For Tomalin, theatre had a baleful influence on the novels: Dickens's plots "tend to the theatrical and the melodramatic", as if theatre and melodrama were self-evidently bad and the same. But for Callow, Dickens's experience as a highly praised but always amateur actor was not the flaw but the making of his writing. It formed his desired, face-to-face relationship with his public (the relationship he was to achieve literally with his readings), in which he and his audience were present in the same room. But it also formed his characters. Callow acknowledges that the highly gestural form of acting favoured in the theatre of Dickens's day is no longer fashionable; but he argues that Dickens's natural power of "reproducing in my own person what I observed in others" is an actorly skill, which – in Dickens's case – involves an immersion of the actor into the character (so, while writing a character's speech, Dickens would frequently leap up to check his own expression in the mirror). Far from pleasurably losing himself inside another personality, as Tomalin describes Dickens the actor, Dickens himself becomes his characters.

For that, Dickens drew on a personality and a biography that was not entirely admirable. He was not a good husband or ex-husband (he issued public statements berating his former wife as a failed spouse, mother and woman). As with many people, his virtues (energy, drive, single-mindedness) implied his faults. But although you could take the book's subtitle ("the great theatre of the world") to imply that Dickens's view of the world was as theatrical as his writing, Callow does not suggest that Dickens's political radicalism – and the considerable charitable efforts that flowed from it – were any kind of affectation. The extent of his polemical and practical efforts on behalf of what the Victorians called "the remnant" and we call the underclass were as considerable as they were commendable. It is one of the many virtues of this book that Callow not only admires his subject, but has got inside him.

Dickens was also – of course – immensely popular, as he still is, though now through dramatisation as much as publication. Callow agrees with Tomalin that Dickens's appeal crossed all classes, but he notes one exception: a literary intelligentsia which then and now mostly regards him with suspicion and condescension. Perhaps that, too, is a legacy of Dickens's love of the theatre.

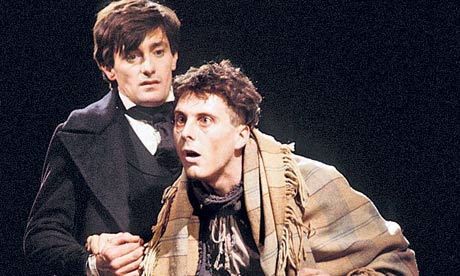

• The television version of David Edgar's RSC adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby will be shown at the BFI on 25 February.