It wasn't just British trade unions that seemed to have a death wish in the late 70s and early 80s. The brightest and bravest of the American unions, United Farm Workers, whose struggle against inhuman conditions in Californian farms inspired a generation, tore itself to pieces. At its 1981 conference, some delegates were found to be hiding handguns under their coats, and when one Mario Bustamente rose to oppose the executive, shouts of "death to Bustamente" were heard.

Frank Bardacke was a player in all this, which doesn't necessarily make him the best person to write about it. Worse: he was not a typical fruit-picker but a young radicalwho started his political activism in the anti-war movement at Berkeley in the 60s. In 1971 he took a job cutting celery in the Salinas Valley and worked in the fields as part of an otherwise Mexican work force, becoming a crew shop steward and, in the down season, teaching agricultural history at the University of California.

Such people in the 70s were often the most doctrinally rigid trade unionists, and it came as no surprise that he has serious criticisms of César Chávez, founder of the United Farm Workers, whom I thought of as a great American hero when I was head of communications for the agricultural workers union here, and whom the UFW still reveres.

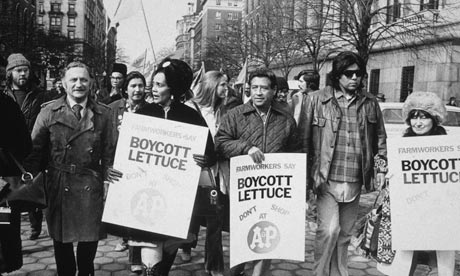

Bardacke thinks Chávez and the UFW leadership and staff were too detached from the membership. It's the charge that used to be levelled against union officials by the Socialist Workers Party here, but was worse in Chávez's case, Bardacke says, because the UFW had a source of income separate from union dues: donations from wealthy individuals, other unions and church groups, and income generated by its campaign to boycott Californian grapes. This, on Bardacke's analysis, explains why its 60s success had fallen away by 1981. He puts the union's achievements down to grassroots action, and thinks too much emphasis has been placed on the leader.

There's a lot more to this book than 60s purism. Bardacke writes movingly and well of the brutal treatment of Mexican farm workers in California, and of the experiences that formed Chávez's beliefs. Chávez grew up in Arizona, where the family home was swindled from them by the people Mexicans in the US call Anglos. His father agreed to clear 80 acres of land in exchange for the deed to 40 acres that adjoined the home. The agreement was broken. A lawyer advised Chávez senior to borrow money and buy the land, but when he couldn't pay the interest on the loan, the lawyer bought the land and sold it back to the original owner, who bulldozed their home.

"César Chávez was 12 years old in 1939 when he and his brother Richard watched the tractor destroy their childhood," writes Bardacke, and he quotes Chávez himself: "Richard and I were watching on higher ground. We kept cussing the driver, but he didn't hear us, our words were lost in the sound of tearing timbers and growling motor. We didn't blame the grower, we blamed the poor tractor driver."

The family took the only work they could get, in the fields of California. "Now home, or what passed for it, was the family's 1927 Studebaker. He slept in a series of tents, shacks, hovels. He travelled among strangers in unknown places, victim of a new set of rules. When he went to the store, he was cheated. He was beaten by older boys."

It was the making of a man whose driving ambition was to build a better, fairer world. The first target of the UFW was the Bracero programme, an arrangement between the US and Mexican governments that lasted from 1942 to 1964, and under which five million Mexican men were contracted to work in the US fields under strict conditions that limited their freedom of movement and kept their wages artificially low.

Bardacke is a talented writer, burning with rage against injustice, and his subject is one of the most attractive and charismatic figures US politics has produced. And yet what comes out – because Bardacke was himself so involved in the detail – is a great slab of a book, 836 pages long, which goes down the twists and turns of every internal dispute in order to pin blame on those the author considers responsible.

In late 70s and early 80s the unions turned inward, eating their own flesh with horrible relish and paving the way for Thatcher and Reagan to destroy their movement. Now they are applying the same doctrinaire cannibalism to their history. It is as true here as in the US – I have written the history of the 1984-85 miners' strike, and have the scars to prove it.

• Francis Beckett's Gordon Brown: Past, Present and Future is published by Haus.