"You disgust me," the Tory MP Gerald Howarth told Derek Jarman during a debate on clause 28 and censorship. Yes indeed, a member of the audience pitched in, adding that Jarman's name was a synonym for "filth". Maybe so, but it was a synonym for much else, as this broad-ranging critical study reminds you. Jarman may have found fame as the moviemaker maudit of Thatcher's Britain, but he was also a poet, an opera set-designer, a painter and an inspirational gardener.

Which is handy, because any long-term reputation Jarman might come to have is not going to rest on his work in the cinema. Well intentioned Jarman's films may be, but have you tried sitting through Jubilee or The Last of England? Notoriety made them noteworthy, but notoriety, as generations of past-it popsters have discovered, is never enough. We tend to think of film as a visual art, but Jarman's movies remind us that the cinema's closest analogue is actually music. Jarman, who once admitted that he didn't "really like the cinema very much", had no sense of rhythm. His movies don't move.

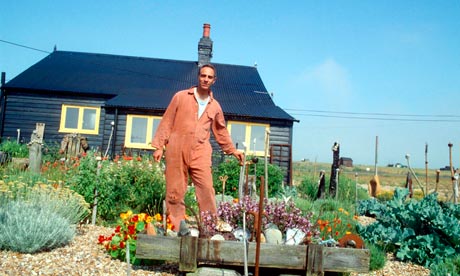

His paintings are something else though. Even in Michael Charlesworth's lamentably reproduced photographs of Jarman's canvases, his kinetic vision bodies forth. A joie de vivre saves even his 1960s student efforts from being mere footnotes to De Kooning. Twenty years later, his imagery had achieved a Johnsian solemnity, their surfaces as sensuously textured as gravestone marble. By the 90s, he was turning out impasto abstracts of such power that even the scraped scrawl of his sententious gesture politics couldn't neuter them. And then there is that spare yet generous garden on the beach at Dungeness, a work of art that people will want to look at for as long as it survives.

Though his formal analysis of individual works can go haywire, Charlesworth tells Jarman's story well in this commendably brief book. Nobody who believes Cole Porter wrote Harold Arlen's "Stormy Weather" is entirely to be trusted, much less anyone who thinks Nicolas Roeg and Jean-Luc Godard "orthodox" film-makers, but otherwise our guide is largely on the money. I hope to never again see a frame of Sebastiane, but that doesn't mean I don't share Charlesworth's regret that it is hard to imagine the picture now getting a release. Times change, and Jarman, who was dead at 52, did less than he would have liked to change them. "I'm an exile in my own country," he used to say. Actually, Jarman fitted well into the angry, agitprop atmosphere of the 80s. How much more of an exile he would feel today.