From time to time, biography is declared dead. Certainly the writer Hilary Spurling said so five years ago when she won the Whitbread book of the year prize for her two-volume life of Matisse. But perhaps she meant the fat literary kind. For in daily life, biography is everything. It is not only the stuff of reality television and gossip magazines and the global appeal of the Daily Mail's gluttonous website: it is also the colour in politicians' speeches and the come-on in popular science and it underlies the invention of the artist as art. Even between hard covers, it still sells. Even a biography of a chief executive. But then we are talking Steve Jobs.

Once upon a time the personal really was personal. Actors were supposed to have rackety private lives but no one needed to know about them. Clement Attlee's irreproachably conservative youth was of no significance to his government's radical agenda, and only a small coterie knew at the time that for 20 years Harold Macmillan's wife Lady Dorothy was in love with and the lover of a Tory colleague. Now it seems everyone lives with their curtains open – and yet the more people reveal, the more people want to know.

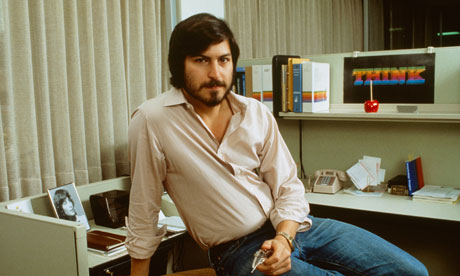

Jobs sought out his biographer, Walter Isaacson, on the strength of his earlier life of Benjamin Franklin. He co-operated with him, opening up for the first time about his family, addressing his shocking behaviour in the office, sharing his moments of catastrophe and even selecting photographs in the weeks before he died.

So in a world without secrets, there plainly has to be some other reason to part with the price of a good bottle of wine for the story of a life, and that is all the truer when it is the story the subject has collaborated in telling. A biography that is authorised risks the deathly hand of sanctity, the sense of an authorial hand stayed by the compact between subject and writer.

The only interesting thing Roy Jenkins told me when I interviewed him about his former cabinet colleague Barbara Castle, of whom I was writing an authorised biography and of whom he thought little, was that I must not publish it until she was dead. "It's impossible to write a good biography when your subject is still alive," he admonished. He himself, he declared magisterially, had made his death a precondition of the publication of his biography.

The death of Jobs was the perfect launch-pad for his biography. But it overshadows it, too. In the New York Times, Joe Nocera says the intimacy of the authorised storyteller diminishes the Jobs biography. How, he asks, can you watch a man die and maintain a sense of distance? Sam Leith in the Guardian suggests that it's not the truth-telling so much as the capacity to be selective that's missing. But it would take more than a little criticism to hold down the sales of a book about the "i" in the 21st century.

So Jobs, even though he was just an amazingly gifted CEO, was a sure-fire winner. It is harder to explain why the authorised-but-unauthorised biography of Julian Assange, hero of the world's subversives, has been such a flop, apparently outsold by a collection of Mills and Boon short stories. Maybe the publishers, Canongate, misjudged their market. People who were interested in what made Assange tick would not also buy a book that arguably was a betrayal in itself, published only halfway through its preparation.

But there was more to it than that. For a start, Assange is not a recently dead hero, but an all-too-alive fugitive from rape allegations whose lack of interpersonal skills has yet to be modified by blistering commercial success. His stock-in-trade was not to be difficult but irresistible. It was just to be difficult..

In fact, if you look at biographies that sell, especially those that sell for months and months, it is hard to detect an obvious pattern. Royalty is a winner, especially in US sales, and within that broad category Elizabeth I is a top pick. Hitler or Churchill in the title is always a good wheeze in the Anglophone market. But no one, probably including its author, would have predicted the extraordinary success of Edmund de Waal's family saga, The Hare with Amber Eyes, now heading for a year in the Amazon top 20. And let's face it, the huge success of Tony Blair's memoir A Journey is a sharp lesson of celebrity as commodity. If in doubt, read Jonathan Margolis on his biography of Lenny Henry for a painful discovery of the importance of biographical sales as an expression of personal success.

Pitching the bestseller ratings of Jobs v Assange says a lot about public attitudes to success and subversion, to the cult of personality and the importance of desirability (yes, Jobs definitely understood about that). But the results say much more about the glorious bagginess of biography as a form.