Martin Gayford's new book about David Hockney is not just, as its title suggests, a record of "conversations". It's a combination of face-to-face encounters and a series of essays that contextualise Hockney's projects over the past five years. Elegantly and simply written, the essays draw you into Hockney's world of country lanes, large studios and famous friends, and into his fascination with light, perspective and the photography/painting divide. But whether you find that world gorgeously beautiful or frustratingly pedestrian will depend on your take on Hockney's visually seductive but intellectually unambitious work.

Since 2006, Hockney has been painting in Bridlington, in East Yorkshire, in a house where his mother and sister used to live. Often, he rises at dawn to catch the early morning sunlight as it dapples the lanes, fields and copses of the surrounding countryside, painting en plein air, as the impressionists did. The book is full not only of good-quality reproductions of Hockney's paintings, but characterful photos of the artist at work, always in his cloth cap, dabbing at his canvases in all weathers, drawing the curving branches of trees with a long brush. The photos are very Romantic in the Caspar David Friedrich sense – a sign of Hockney's rather retro approach.

Hockney began painting Yorkshire landscapes in the late 1990s, driven there by personal circumstances. He planned to return to California but became fascinated by the ever changing light of East Yorkshire. "I'm incredibly daylight-conscious and light-conscious generally. That's why I always wear hats to minimise the dazzle and glare," he says. Gayford does a good job of placing Hockney's current interests in a longer career perspective. For example, Hockney has, in recent years, continued to pursue his longstanding interest in spatial solutions away from perspective, as seen in his paintings of rows of beautiful British trees that unfurl horizontally like a Chinese scroll and recall his large Californian 80s landscapes. He continues to have a love/hate relationship with photography. When he went to the Matisse/Picasso show at the Tate Modern, he thought: "Fuck me, Picasso and Matisse made the world look incredibly exciting; photography makes it look very, very dull." Yet he continues to use photography as a foundation for some of his paintings.

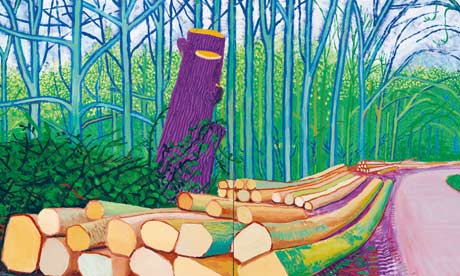

Big paintings remain a trademark. Recent works exhibited at the Tate and Royal Academy, such as Bigger Trees Near Warter (2007), cover whole walls and are made up of more than 60 canvases. Hockney has also started applying the collage approach of his Polaroid works to film. Last year, he mounted five HD video cameras on a rig on top of a moving vehicle to create a multi-screen film that conveys the sensation of driving down a country road. Hockney revisits for us his theory about the pre-history of photography, arguing with good reason that artists as far back as Caravaggio used "cameras" in the sense of "camera obscuras" to project images on their canvas in perspective which they then painted, centuries before the invention of the chemical technology for recording images. The theory is linked effectively to Hockney's use of photographs and digital enlargement for his own paintings, executed in his studio with a team of assistants.

On the whole, Gayford is informative but not probing. I longed for more description of what the studio assistants do, and who actually buys Hockneys nowadays, but the author has a tone that, at times, combines the excessively reverential with the somewhat banal. At the end of one chapter, he exclaims to the artist: "Light creates everything we see." To which the artist replies: "'Let there be light!' – isn't that the start of it all?"

This book, then, will help clear up the mystery of what David Hockney has been doing for the past five or six years, but it will not solve the conundrum that he presents to art critics. Is Hockney a kind of painterly Elton John – someone who has penned a handful of unforgettable visual melodies, whose endurance depends largely on their cheesiness? Or is he a genius of early modernism, born 100 years too late, who has created his own irresistibly beautiful aesthetic that transcends time and place?

If Hockney had been working 100 years ago, I would consider him one of the great colourists of the golden age of modernism. In my fantasy biography, he would have been born around 1870 and emigrated from Bradford to Paris in the 1890s, where he would have mingled with Gauguin and Matisse. Hockney's best pictures – of which there are many – display the brilliant and rigorous colour compositions and strong graphic structure of these artists' work. Like artists from that time, Hockney's subjects are conventional portrait and landscape. Like them, his aesthetic is closely linked to a specific locale. Van Gogh had Arles, Gauguin Tahiti and Hockney had California in the 60s and 70s, and over the past decade he has had East Yorkshire. Hockney's chatter about getting away from western perspective, about light, and the ability of painting to "make you see" would have not sounded archaic in the 1900s. In fin-de-siècle Paris, Hockney's British working-class persona, replete with cloth cap, would have given him a distinctive identity, just as Brancusi liked to dress up as a monk.

For me, the most captivating of the works discussed in this volume are Hockney's iPhone and iPad drawings. In these, the artist combines his remarkably effortless sense of colour and line with a newish, but still quite primitive, technology – in much the same way as the expressionists roughly carved their woodcuts in the 1910s. Drawing on the iPhone and iPad using his thumb, fingers or a stylus, Hockney transforms mundane subjects, like his ashtrays, cloth cap and flowers, into stunning colour compositions. They don't say a whole lot about their subjects, but they unlock the door to a new kind of "free" art for the age of information. "This is a real new medium," he says. "You miss the resist of paper a little, but you can get a marvellous flow." The images are lovely and heartfelt, but leave me wishing that he could have picked slightly less old-fashioned subjects.

• This correction was published on 16 October 2011:

They're bridling in Bridlington. It's a fully fledged town, not a village ("Bridlington's Henri Matisse?" Books, New Review).