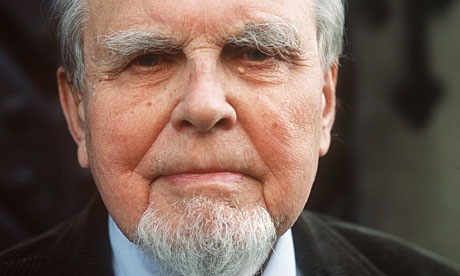

When I interviewed Czesław Miłosz at the Frankfurt Book Fair 10 years ago, he was already a grand old man of letters. He sat with both hands resting on the crook of his walking-stick, looking out from beneath boisterous, white eyebrows like a shepherd surveying a flock. In our 10 minutes together, he spoke only of his childhood and, in particular, of crossing the Poland-Lithuania border every morning by horse and cart on his journey to school.

It could be said that crossing borders – as a messenger, a mediator, a go-between – was the chief activity of a man whose extraordinary life spanned 93 years, five countries, two continents, most of the 20th century and the first years of the 21st. Born in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania-Poland, the Polish Nobel laureate (1980) spent his early childhood in Russia then studied in Vilnius and Poland, before suffering the war in Warsaw, emigrating to Paris in 1951, and taking up a professorship at Berkeley in the 1960s. Spending more time in Krakow, he returned there to live after he was awarded honorary citizenship of the city in 1993.

Last week, Krakow hosted the second Czesław Miłosz festival, bringing together 130 writers, translators and academics for a thrilling celebration of the great man's work under the theme of "Rodzinna Europa" (literally, family of Europe, the original title of his book, Native Realm) to mark the centenary of his birth at the end of next month, just one day before Poland assumes the presidency of the EU. The coincidence is fitting. In the book he writes of "the mélange of Polish, Lithuanian and German blood, of which I myself am an example" and, in the first chapter, "Place of Birth", recalls that his native country "was a wilderness ... It was located beyond the range of maps and belonged to myth and legend". Native Realm explores these imaginary homelands, plus the crueller realities of state and nation and nationalism, of origins and patriotism, but without losing the writer's distinctive capacity for wonder.

In an article, "Being an Émigré", Miłosz wrote, "There is some consolation in the fact that one is not an exception ... there are many of us, not just thousands, but more like millions, for the further the 20th century has progressed, the more new countries have added their wanderers to our numbers." His friend, the Lithuanian poet, Tomas Venclova (who attended the festival) wrote that Miłosz "was forced to choose emigration because he was an enemy of every kind of totalitarianism". See, for example, Miłosz's extraordinarily tense and revealing prose work about moral decisions in extreme circumstances, The Captive Mind, with the writer as "an eyewitness to the crime of genocide, and therefore deprived of the luxury of innocence". Likewise, his poems from the war years, "A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto", "A Song on the End of the World", "Child of Europe" and "Dedication", try to balance the need to bear witness against a survivor's guilt. "I swear there is in me no wizardry of words," he declares, as he pledges to find a simple language to convey such terrible loss. In this role, he saw himself as "the master of defeated despair".

In Poland, many consider Miłosz's essays to be finer than his poetry, for he was a border-crosser, too, in terms of genres, always on the look out for the next form to carry his abundant ideas (his hybrid prose-poem-quotation collection, Unattainable Earth; the alphabet endeavour of Roadside Dog). Then there's his History of Polish Literature (which he updated in 1993 and which remains a seminal work in English) as well as his anthology, Postwar Polish Poets, in which he introduced a western readership to the work of Zbigniew Herbert, Tadeusz Rozewicz and Wisława Szymborska who went on to win the Nobel in 1993. Miłosz himself translated Walt Whitman, and several Chinese poets into Polish, and published a book on the art of translation.

Miłosz's novel The Issa Valley describes the beauty and cruelty of nature and nascent spirituality as conjured by recollections of childhood, while The Land of Ulro probes history, philosophy, politics and religion, to discover a language that can speak of exile or belonging, a sense of oneself against an ever-changing background.

Steadfastly "against a sentimental mythology and a national morality", the poet wonders, "If nature's law is murder, if the strong survive and the weak perish ... where is there room for God's goodness?" Despite believing that one's real moral duty is towards people, and confessing to "wandering on the edge of heresy", he could not give up on God because "I am unable to speak to clouds or rocks". Yet he remained sceptical of the institutional power of organised religion, and often found more comfort in a dreamy lyricism of pastoral splendour, as if he could make these clouds and rocks speak to us, after all, whether on the banks of the Vistula, or overlooking San Francisco Bay.

His poems constantly return us to this sense of wonder offset by a measured solemnity, and by what Derek Walcott called Miłosz's "deep-breathed and oracular rotundity". There is a feeling of authority about Miłosz's work that occasionally hints at arrogance, or at least at an unimpeachable seriousness, but then books and words are "So much more durable / Than we are" and he knew he had a precious gift and a duty to be faithful to his muse. Yet, as a go-between, he also enjoyed his flights into fairy tale and whimsy: "There is so much death, and that is why affection / for pig-tails, bright-coloured skirts in the wind, / for paper boats no more durable than we are". As Tomas Venclova concluded, "Miłosz was able to condense the tragic experience of his era into an invisible point, where hope is born." Considering all he witnessed in his 93 years, that is an extraordinary feat indeed.