Last year I had a moan about cliffhangers in children's literature. I still think they're unholy, the devil's hallmark of publishers chopping one substantial book into fun-sized pamphlets. But I'm losing my knee-jerk antipathy to trilogies. Providing all the books in a trilogy stand alone – with proper endings – and complement one another, the best things really do come in threes.

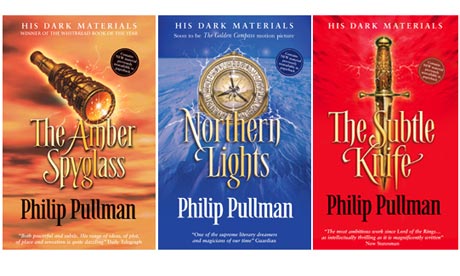

Inkheart, His Dark Materials, Peter Dickinson's Changes, and Jonathan Stroud's Bartimaeus are all superb, and all the better for coming in three volumes. And rather than starting a series which spools away into infinity, it's often good to know that you'll be left wanting more at the end of a third book, not being gradually disillusioned by an increasingly shopworn formula.

The power of three presents its own pitfalls, however. A cohesive trilogy which maintains a constant quality of writing as well as sustaining a reader's interest is a much greater challenge than a single book, and many authors fail to pull it off, churning out second and third volumes that seem lacklustre by comparison, or just a bad fit with what went before. To me, William Nicholson's Wind on Fire trilogy is a case in point. The first book, The Wind Singer, is a self-contained dystopian novel set in the city of Aramanth, where citizens' colour-coded privileges depend on exam results. Featuring sinister "old children" who turn badly-behaved and poorly motivated youth into more of themselves, mud-people who get stoned on tixy leaf, and beautiful adolescent Zars who march into battle chanting "Kill, kill, kill!" the book is light-heartedly compelling. In book two, however, everything goes a bit awry – an invading force sacks the city, slaughtering and burning en masse; the nasty Mastery holds hostages in monkey cages that are set alight if anyone tries to escape; and a woman's face is slashed by a jealous lover. I'm all for dark and uncompromising children's literature, but upping the ante to this extent after the first volume's gentle, PG-rated antics is baffling to me.

I was also a tad disappointed by the second book in Rhiannon Lassiter's Hex trilogy. The eponymous first volume, written at the precocious age of 17, has a fascinatingly dislikeable anti-heroine, Raven, and a gripping future world in which people are literally stratified by wealth – the rich in the Heights, the gangs in the shadowy ground-level slums – and citizens with the Hex mutation are proscribed and executed. While the third book, Ghosts, feeds the reader's yen for revolutionary action as the genocidal elite get overthrown by Hexes, the middle volume feels as though it's marking time – Raven is captured by the security forces, but not a lot happens and not much is learnt.

A good rule of thumb, in fact, is probably to avoid dedicating book two to the protagonist's capture and imprisonment. Patrick Ness's The Ask and the Answer seems much more static than The Knife of Never Letting Go – after Todd's indomitable peregrinations in the first book, he seems to do little but rage against his confinement in the second. Avoiding this momentum-drain, the best trilogies shift place and perspective in their second volumes. After Lyra's betrayal of Roger at the end of Northern Lights, it's gripping and unexpected to find The Subtle Knife opening with a new protagonist, Will Parry, and in a new world – ours. In Inkspell, too, much of the story is told from Dustfinger's perspective within the Inkworld, rather than solely from 12-year-old Meggie's. Dustfinger is a magnificent creation, morally ambivalent and long-suffering, with an Odyssean yearning to get home at all costs that contrasts with Meggie's childlike concern for her parents and new adolescent love-interest. Seeing things through his eyes immediately makes Inkheart's worlds more subtle and memorable, and gives the second book, if anything, more gravitas than the first.

Having broadened their scope in book two, imparted to their work the epic flavour that justifies the trilogy treatment, and written the third book that made it greater than the sum of its parts, writers can rest on their laurels. But it's astonishing how few trilogies remain trilogies throughout their lives. Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea trilogy acquired a fourth volume to become a quartet, 18 years after The Farthest Shore was published. And there have since been two further books, The Other Wind and Tales from Earthsea. And forget Lyra's Oxford and Once Upon A Time In The North – Pullman has been working indefatigably on a full-length novel set in the His Dark Materials universe, The Book of Dust, for several years. Providing there's a long enough gap to make the publication of subsequent books a treat rather than a dilution, I'm quite keen on trilogies in five parts – as long as there aren't any cliffhangers.