I have brought quite a lot of baggage with me to Caryl Phillips's hotel, prosaically close to a roundabout in west London. Metaphorical baggage, that is. Doubts about the way his novels till the same patch of soil - race, identity, the black person's struggle to live and make himself heard in white society. It all seems too right-on, too perfectly suited to awards juries looking for well-written books with Big Themes, too unvarying. When, I intend to ask him, will he produce his sci-fi novel based on 28th-century Pluto?

And then there are the professorships: he teaches EngLit at Yale, is a visiting professor at Oxford, fills half a page of Who's Who with honorary degrees and academic posts, yet fails to mention the names of his parents. I am ready to dislike him and his new novel, In the Falling Snow (terrible title).

Terrible title but, to my surprise, good book. It tells the story of Keith Gordon, a high-flying black race relations policy-maker in his late 40s who is having a full-blown mid-life crisis that embraces a dying father (first-generation immigrant living in the north of England), an estranged white wife (ultra-middle-class parents, racist dad), and a rebellious teenage son. It sounds, in my inane plot summary, disastrous, but is extremely well done - a study in personal isolation and self-questioning against a backdrop of rapid social change.

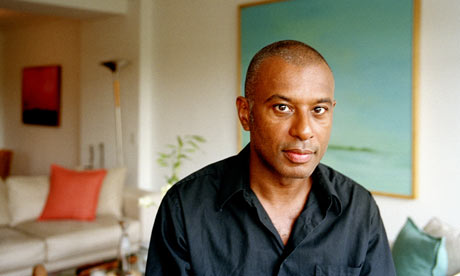

Even more potent in disarming my surliness is Phillips's manner: charming, direct, taking himself seriously but not excessively so. The fact that he immediately makes me a cup of tea, doesn't give me a hard time for not having read his previous eight novels, and has a slow and relaxing (even soporific) way of speaking, in an odd hybrid transatlantic accent, means much of the baggage remains unopened.

But first the easy reductionism: Keith Gordon is 47, Phillips - though he remains outrageously sleek and handsome - is 51. The book, I insist, must be autobiographical. Phillips resists - "There's no real autobiography," he counters at first - but only up to a point. "The main thing is the age," he says. "Keith's at an age where he is beginning to ask himself a lot of serious questions about his life. Obviously I'm over 50 now; when I started to write the book I was roughly that age and was asking myself a lot of tough questions. The world of writing has changed, publishing is changing; you begin to ask yourself questions about what the hell kind of business have I got into. A couple of weeks before this book was published my editor was fired. It would be wrong of me to pretend that these questions weren't pressing upon me."

Unlike the character in his book, Phillips does not have an estranged wife, nor any rebellious children, and their absence may be among those pressing questions. "Caz", as he is universally known among the literati, is much admired by women, and would not, one suspects, have been short of offers of marriage. Has he ever come close to accepting any? "Yeah, a couple of times," he says. "I think I can say now, with hindsight, it was my loss. One person [with whom he had a relationship about 15 years ago] came to New York recently with her two children and we went to the park, and after she'd gone the rest of the day was miserable. I was thinking first how great she was and how fantastic her kids were. I had a great time with them, and I did have that moment - you might even call it a Keith moment - where I spent most of the rest of the day shaking my head, thinking 'What did you do? You complete idiot!'"

But he was already married: to his work. "Some time ago my mother gave up on me, gave up on grandchildren from this particular son," he says. "And she said something very sweet. She said, 'I suppose you must at some stage have made a decision that you wanted the books; you didn't want the kids.' I'd never really thought of it like that, but what I did think of very early on was a comment made to me in 1982 in Alabama, where I was making a documentary for ITV. I was driving a politician to a rally, and he asked me, 'Are you serious about being a writer?' I said, 'Yeah, yeah, this is what I want to do. I'm here writing this documentary and I want to write novels eventually.' He went very, very quiet for a long time and he didn't take his eyes from the road, and then he said, 'Well, I think you should choose your female companionship very carefully.' I remember the phrase. It had both the weight of authority and this weird construction - 'female companionship'. I think I've just been very committed to what I'm doing."

Phillips's moral purpose is rooted in his background. He was born in St Kitts, in the West Indies, but his parents brought him to the UK at the age of four months, and he grew up, the eldest of four sons, on a council estate in Leeds. By race and by class - a bright boy at a grammar school - he was an outsider, and he knew it. "The society reinforced negative stereotypes," he says. "Every black kid had the experience of going to school and people calling them a nignog, because that's what was said on the TV last night and the black characters laughed, so what's your problem, pal?"

Expectations of black boys, even bright ones like Phillips, were low: at 14, a teacher congratulated him on the progress he was making and said he could look forward to getting an apprenticeship. Instead, driven on by parents who had ambitions for all four of their sons, he won a place at Oxford to study English, where he had to face being the "exotic other" all over again.

This has left a mark on his work - its preoccupation with race, class and identity; its moral striving; its search for a purpose. "I want to change Britain," he says. "I want us to become more aware of our own history. If I can write about how Britain as a society is transforming itself, then maybe one is filling in some of the gaps that have been left out by the media, by history, by the politicians."

The irony of his new book is that it is a densely detailed English novel written by a Briton who has spent much of the last 20 years at US universities - he currently teaches contemporary British fiction at Yale. Home is midtown Manhattan, and Phillips accepts that his peripatetic life revolves around New York. "It's been a very comfortable place for a lot of people who've got a strange relationship with self and their country," he says. "There's an anonymity, a peaceful anonymity. I became somewhat invisible. My natural inclination has always been to be the one peeking round the corner of the curtain, and America allowed me to be like that."

But the UK remains his spiritual home. A visit to London a couple of years ago, and the sight of the vast Westfield shopping centre obliterating bits of Shepherd's Bush that he knew well, made him want to reconnect with the country that remains at the centre of his imagination. "I wanted to re-engage with a London that I felt I was drifting away from," he says.

The result is a portrait of three generations of Britons - his parents', his own, and that of the children he never had; a book at once intimate and broad; small lives on a big canvas. "I could see an older generation who had grown up with one conception of what Britain was. That generation's - both black and white - conception of Britain is very different from my generation's conception of Britain, and in turn the new generation of kids have an entirely different conception of Britain and a different conception of self as a result. It was an interesting moment to be able to see three different ideas of Britain trying to grapple with each other and occupy the same space."

Laurie, the rebellious teenager, is drawn towards gang culture and gets involved in a stabbing, but he can be rescued. Phillips is resolutely optimistic about this new generation, not least because they no longer have to play the exotic other. "I think these kids are a lot smarter, a lot more sussed out, a lot more confident than I and my generation were," he says. "I like their ownership of Britain; I like their sassiness. It comes with dangers because that degree of confidence and ownership can lead them into trouble - perhaps they don't see boundaries as clearly as we did - but I don't think it's just about knife crime and asbos and drugs."

So, finally, the Pluto question: is it time for Phillips to leave his fictional comfort zone? "All writers are territorial," he says calmly. "They're like dogs marking their territory. The great task of being a writer is to discover what your territory is, and you do revisit similar themes in different ways. I think I'm very lucky to have found a patch of earth which resonates very powerfully with me because of my own personal life history, but also seems to resonate powerfully with the narrative of the country." The sci-fi novel will have to wait.