Everyone will be struck by the boldness, scale and exhilarating freedom of many of the paintings in Howard Hodgkin's new show. None of these qualities is new to him: he has been making very large paintings much more frequently over the past eight years, and some of them, such as the huge unframed Rhode Island (2000-02), have been very wildly painted, as if he were out of patience with the seductiveness and refinement he so naturally commands. He has just completed a quartet of paintings that seem to tap into the same American freedom, and take their titles from a song that is a kind of unofficial anthem of the American west. But the familiar words of "Home on the Range" have elicited from Hodgkin something no one could have anticipated: a sequence that moves from the terrain of his art as we think we know it towards the most radical experiment he has yet made.

It begins with another big fierce landscape, Home, Home on the Range, which reminds you that "home" may be far from homely - and perhaps, in Hodgkin's own case, far from home; he was evacuated from England to the United States at the age of eight, a dislocation that also gave him his first direct contact with much of the greatest modern art, and showed him the necessity of becoming an artist himself. This new painting was started seven years ago, and shares something of the roughness and restless agitation of Rhode Island. Similar dashes in red and brilliant cadmium yellow flicker in the foreground; the framing effects, like theatre flats, with which Hodgkin frequently structures a painting, are impetuously painted over; the sky is hectic and hurrying, the colour contrasts powerful and unsettling. In many of his paintings, Hodgkin famously works with a found frame, which is then lavishly painted over. They intoxicate by being all paint, and even on the smallest scale can overwhelm you with their refusal of conventional distance and distraction. But increasingly now he is leaving the bare board clear, as the ground of the painting itself, and as the margin in which the business of the picture raggedly stops or starts. Your attention is still drawn to the means and the medium, but in a different way.

Where the Deer and the Antelope Play is a gentler painting, and a simpler one. Long lines of underdrawing left visible mark a horizon between a gorgeously flaming sky and a yellow-green sweep of prairie so intense that the eye almost flinches from it. Sumptuous dark blues provide a kind of proscenium for a primitively idyllic scene. The deer and the antelope themselves must be imagined - this is merely where they play. And the sense of play expands in the jubilant third panel. The quaint phrasing of the song allows that a discouraging word may occasionally be heard, but the few dark accidentals in Hodgkin's version are swept away in a dance of unstoppable energy, the colouring of Matisse-like simplicity, a dazzle of blue dashes above rolling swathes of yellow and orange. Where Seldom Is Heard a Discouraging Word gives form to the Romantic notion of a landscape smiling, even to the hymnist's notion that the valleys laugh and sing.

And what then? The fourth movement is not a symphonic finale, but a kind of dissolution, a painting all in one colour - or, more strictly, in two, since so much of the pale board that the green paint flashes across is left bare and contributes its own tone of faintly gleaming vacancy. In fact, for all these paintings, each nearly seven feet high and nine feet wide, two boards are joined together. In And the Skies Are Not Cloudy All Day, most of the action is in the upper half, the paint scurrying and gathering towards the right, while down below a couple of dozen dashes of paint leap and tumble across empty space. The painting gives a sense of headlong speed in the execution, a masterly scribble. It is different in character from Cy Twombly's scribbles, but it has a comparable sense of almost haphazard sublimity. If part of the vividness of this sequence comes from Hodgkin's memories, in old age, of his American boyhood, a passionate backward glance, then its final panel is all the more remarkable for the lack of any sense of recapitulation. It moves on; and it is very hard to see where, beyond total silence, it could go next. It is the end, at least of this particular song.

The paintings of Hodgkin's 70s often have a turbulence, capturing and taking animation from movement and flux, that was perhaps less evident, less urgent, in earlier years, when he seemed more bent on the patient stalking of memory and feeling. Those characteristic blobs or dashes, which seemed to camouflage the very thing they were describing, may now be the sole kind of mark in an entire painting. In his biggest ever work on board, Autumn (1998-2003), the blobs had become leaves, half-concealing the landscape as they streamed across it on the wind. The painting's relative simplicity of structure and means enhanced the metaphysical power we feel more and more strongly in late Hodgkin. His recent interest in pairs, or even quartets, of paintings strengthens this visionary strain through grand thematic contrasts. Four years ago, there were two great paintings in identical formats, Come Into the Garden, Maud and Undertones of War, one an exuberantly floral vision of love, the other the most brutal and angry painting Hodgkin has ever done. Both were full of movement, whether revelling and free or relentless and stabbing. Together they were complete, and irresolvable.

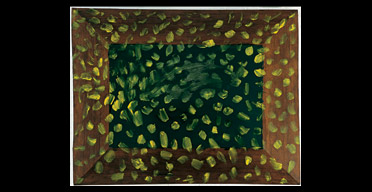

The new show contains another pair, of comparable magnificence, House and Garden, made entirely out of blobs on a dark ground. (I'm aware that "blob", "dot" and "dash" are crudely inadequate terms for one of Hodgkin's most complex and individual kinds of mark.) They use to the full a pair of very broad and deep, perhaps 1930s frames, stained a rich deep brown, and slightly warped in a way that lends them a further twist of energy. House is painted all in reds and oranges, a tremendous storm or swarm of dots, as dense as humanity in its migrations, its collisions and overlappings. The central board can't help but seem an opening, or portal, through which the richly coloured motes swirl and stream. The house, as if read by a thermal-imaging camera, glows with occupation, activity, the incessant comings and goings of the moment and of the years. Garden is clearer, more regular in its marks, an airier realm where nature delights but is kept in order, and yet rebels. The frame has the colour of moist earth, against which the yellow and green dashes take on almost luminous intensity. Across the centre, there is movement among the leaves, and the forms blur sexily, in a kind of pollenous smear. There is another Hodgkin called Garden, painted 45 years earlier, a nearly symmetrical view through an archway; and gardens have made subjects of many different moods and implications for him since. But there has never been one so radically simple or so vitally mysterious.

You always want to get close to a Hodgkin. The sensory, sometimes visceral impact of a painting when first seen is followed by a long, evolving negotiation with it, a move into intimate reverie and speculation. The marks he makes, often with a large brush heavily laden with different-coloured paints, are among the great virtuosities of modern art. Their immediacy and bravura strike you from across a room, but as you get closer and closer they draw you in to what seem little landscapes in themselves, yielding up greater and greater riches, and even giving a slightly hallucinatory sense of their being other paintings within the painting, a sort of dreamlike double take. Instinct and spontaneity are at one with inexpressible mystery.

Exactly how it is done, day by day or year by year, is itself a mystery to most of us. It would be fascinating to watch the growth of a painting over several years, the occasional removal of the screens with which works in progress are concealed in the studio, as if perhaps to spare them the abrasions of familiarity, and to foment them in the imagination; then the pondered but surely rapid additions, the undisguised overpainting that lends so many Hodgkins a further sense of mystery, of semi-concealment in layers. Occasionally in the past a painting has been exhibited, revised and then exhibited again; anyone with access to the catalogue raisonné can compare the versions and glimpse something of the process.

Hodgkin can be all candour, nakedly emotional, and at the same time leave you guessing. Something essentially intuitive in his art expects intuition in the viewer. His art seduces, but partly by flattering you with the confidence that you will be quick and keen enough to respond: it works by a kind of erotic certainty. You can feel teased by a Hodgkin, your interest piqued, your curiosity titillated. His subjects, of course, often are erotic, flushed with amorous feeling and refinements of feeling. "Privacy and Self-Expression in the Bedroom", in the new show, has an unmissably Hodgkin title (which is also, amusingly, a found title: a chapter heading from a 1950 book on interior decoration). The painting itself is warmly expressive, and also pretty private, visibly drawing a veil over the rich-hued life within; and playing, like so many Hodgkins, with the paradoxical implications of scale: an intimate subject, which might have made for one of his intense small paintings, given a treatment five feet wide. The mind zooms in and out as it thinks the thing through.

The uncertain thresholds of intimacy are treated very wittily in the new painting Blushing. It is a pair to Degas' Russian Dancers, a darker painting of the same size, which is perhaps a memory, or vividly transformed sense-impression, of Degas's pastel in the National Gallery, itself an "orgy of colour", in Degas's own phrase, and from his late career. Now the dancer's skirt swings in a heavy orange-and-black diagonal across the board, a form like a flaming Zeppelin sinking right off the edge of the frame. In Blushing, however, the diagonal form is slightly curved, one of Hodgkin's big right-hand arcs, and, far from sinking, it is perkily and irrepressibly tumescent. Its background is a happy stirring of pink blobs over paler pink streaks, giving a sense of simultaneous delight and confusion. A blush, after all, is a sign of a secret, a rushing to the surface of something hidden but no longer deniable, though to us as viewers its cause may still need to be guessed at. The frame the artist has chosen is especially apt and suggestive: an unfinished one, partly traced over with a conventional pattern of flowing foliage, as a guide for the wood carver, who has made the first shallow etching-out of the shapes along the top edge, but has as yet left the left-hand edge virtually untouched. The paint makes almost no incursion on to the frame, so that the sensitive subject appears contained within a structure which is itself only partly defined, a matter of decorous gestures that the suffusion of blushing challenges but does not yet break free of.

Hodgkin has long been alone in his command of such nuances, and shows no sign of abandoning his recherche of emotional truths, in all their elusiveness and contrariety. What shakes you is that at 75, when many artists fall victim to their own habits, good or bad, he should also be making work so recklessly and unanswerably new.

· Howard Hodgkin's exhibition of new paintings is at the Gagosian Gallery, Britannia Street, London WC1, from April 3 to May 17.