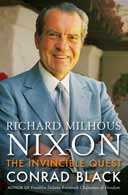

Richard Milhous Nixon: The Invincible Quest

by Conrad Black

1,152pp, Quercus, £30

He was a Quaker, lawyer, statesman, streetfighter and crook. There were at least five different Nixons (as Henry Kissinger once observed) and the fascination lies in seeing how seldom the split personalities meet. But there are many different Conrad Blacks as well, which is what gives this vast biography its special savour.

One moment Black plays scholar, the next he's a political tyro advising his beleaguered subject how to reconstruct his cabinet or lie his way out of Watergate. One moment he's the lofty press baron we used to know; the next, he's spitting at the frailties of journalism, from Cronkite, Woodward and Bernstein down. He is a peer of the realm, aspirant professor, pundit, good companion and money man. Always, in each passing persona, Black knows best. It makes for a rollicking read.

Members of this (American) jury ... does the hapless Canadian in the dock before you admire every president since Herbert Hoover (bar "pathetic" Jimmy Carter) with eulogistic reverence? Indeed, he does. Eisenhower and Reagan turn titans through these pages, trooping into history only one pace behind Roosevelt. Does he, straightfaced, recall Nixon's pledge to write books in prison, if necessary? Can he possibly, in his industry and wisdom, be the kind of slimy financier the prosecution would like you to see, decking his wife in million-dollar trinkets and ripping his once-proud company to shreds? Is he not, in all conscience, a formidable man?

Any continuing jury has much to argue over. Black's first monster - his FDR biography - was written and researched before the Hollinger empire disintegrated. It proved a thorough piece of work, revealing an unlikely enthusiasm for New Deal politics but otherwise plodding earnestly along well-trodden paths. The Nixon book, like Nixon himself, topples from a quite different shelf. Roosevelt was a great man. No controversy - or even much interest - there. But Nixon, the argument runs, was also a politician of great talent, and a man traduced. Black, on behalf of traduced chaps everywhere, has to come out of his corner fighting. Mere facts aren't quite enough.

That doesn't mean a work short on facts, of course. The Invincible Quest heaves with them. Intricate set pieces - such as the Chicago convention of 1952 that Nixon, manipulating behind the scenes like some Jacobean villain on speed, handed to Eisenhower while appearing to stay loyal to California's Earl Warren - have never been better rendered. But the facts alone aren't entirely fit for rehabilitation purposes. How do they rescue the only slightly more respectable face of un-American activities witch-hunts from the same fate as Joe McCarthy? Nixon was tricky from first to last, carving up hapless opponents who played by the rules, first with the slur that hurt most, always liable to break into foul rages against "that senile old bastard" Eisenhower (or any younger bastard who crossed him). You can't show that the real Nixon was better than this. You have to tell us so, with conviction. And Black can't pull that off all the time.

We can marvel at some of the dirty tricks Nixon played on the way up. We can feel a kind of awed nausea as his "Checkers" TV speech summons a beloved pooch to rescue a vice-presidential career from corruption charges. We can certainly admire his quiet work on desegregation, the dexterity of his foreign tours, the zeal he applied to Vietnam disengagement, the headlines of the great trip to China. Nixon was often a class act as streetfighter and statesman. But the sum of these parts still leaves him far short of Black's thesis.

He didn't "tragically" lose his bearings as he stumbled deeper into Watergate. From his earliest days as a student politician in California, standing for every election possible and learning a tawdry trade inside out, he had difficulty with bearings. But the isolation of the Oval Office, and his lack of any decent friends, left him bare-faced. Watergate was a disaster that took three decades to happen. Maybe, as Black says, it was ridiculously overblown by a mindlessly triumphal press. Maybe no one got hurt, or rich, in the process. Maybe Whitewater 20 years later is another example of much ado about nothing much. But it was the little things about Nixon on the way up that left the nastiest taste - and little things brought him down. He could be industrious, perceptive, articulate, but the flaws piled up, year after year, crisis after crisis.

So we're back to the inevitable second strand here, to Richard M Nixon as an invincible model for Lord B of Crossharbour. Was Nixon only a shyster? Of course not: he was much more than that. Black - on this form - is also much more than your average, controversy-ridden press baron. He has a rare talent for serious history, and the talent to tell it well. Watergate isn't just regurgitated in this account: it is clear and set in a rational context. How could he toil to such solid effect in the midst of such personal strife? It's remarkable.

But it is also calculated. Set Nixon against Kissinger, rivals as well as partners, and you'd think Kissinger (a Black appointee to the Hollinger board) would get rave reviews. Not exactly. Kissinger was a "self-absorbed egotist", a malignant gossip, a master "of scraping the barrel with his obsequious memos and asides" - while "loyal Richard Nixon" was "touchingly generous countless times in his life" but, in his loneliness, sadly vulnerable "to the counsel of extreme cynics and people of thuggish mien".

Consider your literary verdict carefully, members of the jury: and try to remember exactly who's there before you in the dock.