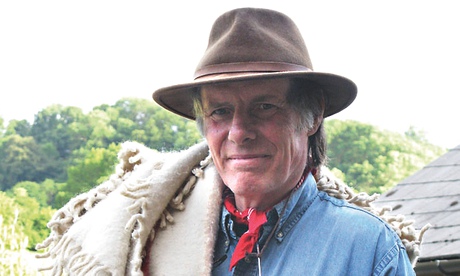

Patrick Whitefield, who has died aged 66 after a short illness, drew on his boyhood love of the landscape, plants and animals to become a leading advocate of permaculture, an approach to farming that maintains both food production and the balance of nature. With his guiding principle of “nature as teacher”, he helped transform growers’ attitudes towards permaculture from its previous marginalised status in the debate about sustainable farming.

As a child, Whitefield always wanted to be a farmer, and on leaving the Catholic public school Downside, near Bath, he studied agriculture at Shuttleworth College in Bedfordshire. However, he soon realised that he would never be content as a farmer because, as he remarked, “my boredom threshold is far too low”. After college he spent several years working in agriculture in the Middle East and Africa, where he contracted the cattle-borne disease brucellosis, an illness that caused health problems for the rest of his life.

On returning to his beloved Somerset, he bought a flower-rich hay meadow, the White Field, near Butleigh, with the intention of maintaining it as a nature reserve. For eight years he lived in a tipi on the meadow, working as a craftsman.

His first book, Tipi Living, published in 1987, was a taste of things to come. He became a prominent member of the Ecology party, which later became the Green party, and was involved in the early years of the Glastonbury music festival. Born in Devizes, Wiltshire, the son of Michael and Peggy Vickers, he changed his name from Vickers to Whitefield in honour of his meadow home, which he subsequently entrusted to Somerset Wildlife Trust “for safekeeping”.

What was arguably the defining influence on Whitefield’s life resulted from his learning about a new ecological approach to agriculture from two Australians, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, who had written widely about designing farms and gardens that mimicked natural ecosystems. Whitefield was intrigued. He signed up for a permaculture design course, after which he drew on his experience to date to dedicate himself to the permaculture approach.

In 1990, he married Cathy Lowenstein at the Chalice Well Gardens in Glastonbury, where they later settled. They soon began running their own courses together at Ragmans Lane Farm, a pioneering permaculture farm in the Wye Valley, Gloucestershire, teaching permaculture design and sustainable land use. The success of the courses owed much to a combination of Whitefield’s encyclopedic knowledge and Cathy’s communication skills.

With permaculture little known at that time, the task of building up the courses required great dedication, but glowing reports from participants kept them running and their popularity grew. His colleague Caroline Aitken said: “Patrick’s gift as a permaculture teacher was not just his warmth and charisma, but the clarity of his understanding – the kind of clarity that enables a penny to drop within the mind of the listener.”

The courses led to a series of books. In 1993, Permaculture in a Nutshell introduced the subject to people in temperate climates. While permaculture principles apply everywhere, Mollison and Holmgren’s work focused mainly on arid and subtropical climates and so there was little information for the practical application within milder temperate zones such as Europe and much of the US.

How to Make a Forest Garden (1996) is a practical guide to creating a perennial kitchen garden modelled on a young woodland ecosystem. Here crops are grown in layers: perennial vegetables and herbs on and under the ground, soft fruit on bushes, and fruit and nuts on trees. The Earth Care Manual: A Permaculture Handbook for Britain and other Temperate Climates (2004) acted as a text book on temperate permaculture for staff and students. By this time, Whitefield’s courses had waiting lists and he was invited to teach and speak all over the world.

Whitefield contributed regularly to Permaculture Magazine, where he was a consultant editor, and other publications. He appeared on the BBC’s It’s Not Easy Being Green (2006) and A Farm for the Future (2008) and attracted a large global following on his blog and on social media, where he was not only respected for his wisdom and expertise, but was well-loved for his charismatic yet humble character. Two further publications, The Living Landscape: How to Read it and Understand It (2009), and a field guide, How to Read the Landscape (2014), explored his passion for understanding the ecology of landscapes.

It was only towards the end of his life that the wider significance of permaculture ideas began to emerge, as it gradually dawned on growers that food production is actually about the management of ecosystems. Hitherto, not only mainstream agriculture, but even the organic movement paid insufficient attention to permaculture, wrongly believing that it would produce too little food and require too much management to be adopted on a commercial basis.

As someone who shared some of those prejudices, I have come to realise only relatively recently that regarding nature as teacher will best improve the sustainable productivity of my own farm.

As with so many of those who challenge orthdoxies, the true significance of Whitefield’s ideas was not adequately acknowledged during his lifetime, but his influence will survive him, under the stewardship of the many he influenced along with Aitken at Patrick Whitefield Associates. His example will continue to remind food producers that instead of plundering natural capital through industrial agriculture, farmers of the future will have to devise of ways of co-existing with nature.

He is survived by Cathy, and a son, Caleb.

• Patrick Whitefield (Patrick Vickers), permaculturist, born 11 February 1949; died 27 February 2015