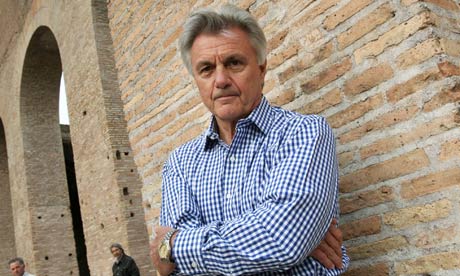

It has always seemed appropriate that John Irving is the only great contemporary novelist to have been inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He goes about his writing much as you imagine he used to go about his former life as a college grappling champion and subsequent obsessive hobby as a coach. Subjects are faced down, language approached with muscular intent and no little adrenaline, and the whole eventually coerced into satisfying submission. It's not a criticism to say that he is the kind of novelist who carefully measures up a character from every angle and knows every trick in the book; the thrill of his books is the way he sets about establishing complex individuals who generally come out fighting.

In this sense, Billy Abbott is a character to set alongside those indelible Irving creations of the past, Garp and Owen Meany and Homer Wells of The Cider House Rules. You root for him from the outset. And when his story visits on him some of the more outrageous fates that Irving can conjure, you don't give up on him.

Abbott is a novelist himself. And like many novelists, like Irving himself, whose biological father left when he was two, he has a dad-shaped hole. Billy fills this space – left by a father who never came back from the war – in different ways. To begin with, he fills it with teenage crushes. He has a crush on Miss Frost, the statuesque librarian in his home town of First Sister, Vermont. He has a crush on his stepfather, Richard Abbott, the English teacher at the private school he attends. He has a crush on Kittredge, the Greco-Roman school wrestling champion. This is 1955, however, and crushes on boys are things to inform the authorities about, things that can, as Dr Harlow, the school principal, sets out in no uncertain terms, be cured, like teenage pimples.

Billy Abbott, of course, looks for the antidotes to his crushes in different places; if the 50s tell him to subjugate his desires, wrestle with his demons, the 60s and 70s challenge him rather to pursue them wherever they lead him. And once Billy has embraced his bisexuality, his body's refusal of gender boundaries, his whole world seems to take on an androgynous cast.

Billy's mother is the prompter in the amateur dramatic society where his Grandpa Harry has a history of taking the female lead. Miss Frost, the librarian, sees a kindred spirit in Billy and initiates him into a world he had hardly dared to imagine. His stepfather seems complicit, too, in his search for sexual identity when he sets Shakespeare loose among the jocks of the Favorite River Academy and finds among the wrestling team plenty of would-be Titanias (and not a few Bottoms). The Elizabethan shape-shifting and cross-dressing take on a decidedly New England cast and Irving plays it for all he is worth.

As ever in his novels, time becomes a central character; if Shakespeare is foregrounded in the plays within this play, the thrum of bardic themes of love and death and mutability is never far away. Billy, when explaining his desire to be a writer at 17, thinks of his subject as lost innocence, already mourning a fabled past. "Well," says the wise Miss Frost, "if you are nostalgic at 17, perhaps you are going to be a writer."

That sense of a lost golden time inflects Billy's reminiscensces as he looks back on his life from the vantage of 65-year-old literary notoriety. What begins as a kind of coming-of-age memoir, in which he learns to be himself in the company of drag queens and transsexuals, in the bath houses of New York and opera houses of Vienna, becomes something far darker as Aids begins to destroy this likable masquerade in the early 1980s. Irving details the shift with candour; having spent half a life in beds rarely his own, Billy now sits at bedsides and has sad conversations with living corpses, lovers he used to know.

Irving is not a novelist who enjoys loose ends and he ties up each of his plot strands here one by one until they form a satisfying pattern. His novel is many things – a little slice of cruel history precisely told, a kind of back-to-front mystery in which veils of deception and self-deception are lifted one by one, a sort of love story in which love rarely travels in the directions you imagined. Most of all, though, it is another of this writer's bold hymns to individuality, to the great American quest of self-discovery; even Donna, or Don, one of Billy's transvestite lovers, is at a loss to define the protagonist of Irving's novel at one point: "You're not like anyone else, Billy – that's what's the matter with you," she says in a moment of whispered pillow talk. As we have already come to realise, Billy is not alone in that particular affliction. As the book triumphantly suggests, difference is one problem shared by everybody.